The Finance Minister, during her recent budget speech claimed that more than 6 lakh Anganwadi workers have been equipped with smartphones to upload data real-time. We look at this fact as well as the promises and limitations this system holds.

The 2020-21 Budget Speech, delivered by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, presented achievements of Poshan Abhiyan. In this article, we fact-check the claim and understand the trajectory of monitoring mechanisms under the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) or popularly known as the ‘Anganwadi’ scheme.

Claim (Point 66): To improve the nutritional status of children (0-6 years), adolescent girls, pregnant women and lactating mothers, Prime Minister launched a ‘Poshan Abhiyan’ in 2017-18. More than six lakh Anganwadi workers are equipped with smart phones to upload the nutritional status of more than 10 crore households.

Fact: The claim is TRUE. As on 31 December 2019, 6.08 lakh Anganwadi workers are uploading data on ICDS – Common Application Software (ICDS-CAS). However, numerous challenges exist in making this work.

What is new about monitoring under the Poshan Abhiyan?

The Poshan Abhiyaan was launched in 2017 as a flagship scheme focussed on tackling the deeply entrenched problem of malnutrition, given the backdrop of a National Nutrition Strategy ‘Nourishing India’ released by NITI Aayog in September 2017. The strategy presented an in-depth analysis of the 4th round of the National Family Health Survey and identified bottlenecks that were hampering the effective delivery of existing health and nutrition programs.

Under the program, the ICDS- Common Application Software (ICDS-CAS) was rolled out in 2018 to meet the challenge of time-consuming data management and ensure better monitoring of progress. The software is pre-loaded into mobile devices given to the Anganwadi workers. As per the information shared by the government, the software simplifies and digitizes data management by auto-generating, among other things, lists to identify children at-risk and upcoming immunization dates. It enables data capture, ensures assigned service delivery and prompts for interventions wherever required.

This data is then available in near real time to the supervisory staff from Block, District, State to National level through a Dashboard, for monitoring. The procurement and distribution of mobile devices is a part of the project. Interactive videos on appropriate care practices during pregnancies, feeding related information, childcare practices, disease management have also been in-built within the software. The use of technology is crucial to the monitoring mechanism of the program. For instance, the use of geo-tagging and date/time stamped photos enable a check on the number of visits by the supervisor.

The annual reports of the Ministry of Women & Child Development highlight the use of ICDS-CAS application by Anganwadi workers. The 2018-19 annual report stated that a total of 2.15 Lakh Anganwadis were effectively using the job aid for service delivery and reporting. In 2019-20 report, this number increased to 6.08 lakh Anganwadi workers, as on 31 December 2019. Therefore, the claim made in the budget speech stands TRUE.

However, it is important to understand the genesis of ICDS and the monitoring mechanism that was being followed before the introduction of the tablets.

Challenges associated with monitoring under the ICDS umbrella

The ICDS was launched as a centrally sponsored scheme on 02 October 1975 by Ministry of Women and Child Development. Three major services, namely, supplementary nutrition, pre-school education, health and nutrition education, are delivered by Anganwadi Centres at the village level.

The monitoring and evaluation framework under the scheme is a three-tier setup: the national, the state, and the community levels. The ICDS Scheme envisions an in-built system of monitoring through regular reports flowing upwards from the Anganwadi centre to Project Headquarter, State Headquarter and finally to ministry.

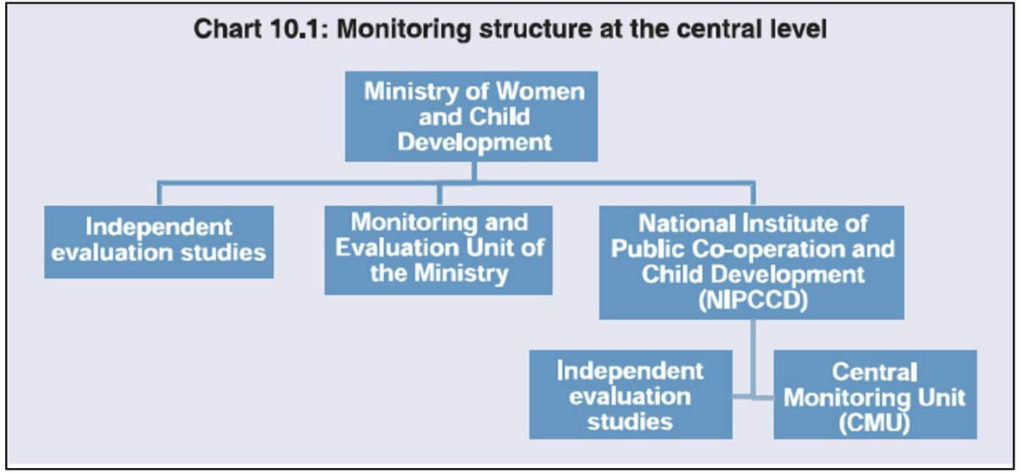

The CAG’s (Comptroller and Auditor General of India) Performance Audit Report of 2012 about the ICDS highlights that the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) unit was the sole monitor of the scheme till 2006-07. To establish a regular monitoring and supervision mechanism, an autonomous body of the ministry called the National Institute of Public Co-operation and Child Development (NIPCCD) was set up in the same year. With the appointment of one consultant, this body was established in the form of a Central Monitoring Unit (CMU) in January 2017. While the NIPCCD was responsible for hiring a team of six consultants with relevant domain expertise, the audit found that the operations of CMU were managed with professional consultants for most of the period during 2006-11.

It was only in October 2008 that the monitoring and supervision projects in states became functional when NIPCCD identified 42 academic institutions as selected institutions in 2008-09. The CAG report identifies administrative laxity on part of the NIPCCD as the major reason behind the delay in establishing monitoring practices.

Until March 2012, no concurrent evaluation of ICDS on scheme outcomes and nutritional status were carried out by CMU. Only concurrent evaluation reports on input indicators were prepared, focussing on issues such as infrastructure of Anganwadi centers, status of supplies, supervision by Child Development Project Officer (CDPO), status of community participation, and ICDS delivery status. In addition, the data used for preparing these reports were not concurrent. For instance, the evaluation report published in January 2012 contained data as old as March 2009. Furthermore, audit also found that CMU did not receive monthly, quarterly and annual progress reports consistently from states.

The M&E unit under the ministry also failed in furnishing any impact assessment of the ICDS services. The audit noted that the monitoring was restricted to quantitative aspects and qualitative parameters like nutritional status of children and effectiveness of scheme remained neglected even after three and a half decades of the scheme’s launch.

In November 2012, the ministry announced that a five-tier monitoring and evaluation scheme and a revised Management Information System (MIS) would take care of the short comings emerging out of CMU reports. The guidelines mandated formation of various committees and regular meetings to monitor and review the progress of scheme. However, the CAG’s Performance Audit Report of 2017 notes that, between 2011-2016, requirements of the guidelines were not met either due to non-formation of committees or due to lack of consistent meetings. Therefore, issues such as shortfall in coverage of beneficiaries, delays in construction of AWC buildings, and under-utilisation of funds could not be effectively addressed.

The promise and limitations of ICDS-CAS

NITI Aayog’s Progress Report on Poshan Abhiyan (September 2019) notes that the ICDS-CAS application intends to ensure better service delivery and supervision as well as enable real-time monitoring and data-based decision-making. This ICT leveraged solution is expected to help to improve the nutrition levels of children in the country and help meet nutrition goals. The application digitizes 10 of the 11 registers of the Anganwadi workers, provides a supervisory application for the officials, and a dashboard application to CDPOs, DPOs as well as to officials at the State and at the central level to be able to monitor Anganwadi Centre (AWC) activities

The Report also notes the challenges reported by states in rolling out ICDS-CAS.

- Poor connectivity has been cited as the most common impediment to mobile phone functioning at ground level in states such as such as Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Puducherry, Mizoram, Meghalaya and Nagaland.

- Delays in training and procurement of ICDS-CAS were faced in Haryana, Jammu & Kashmir, Maharashtra and Punjab.

- Issues related to app and device performance and usability are reported by Chandigarh, Daman and Diu, Madhya Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu.

- Other states faced several state-specific issues. Punjab and Rajasthan face budget constraints, while in Maharashtra, vacancies posed a significant challenge for the implementation of ICDS-CAS. In Himachal Pradesh, ICDS-CAS is not linked with PMMVY, leading to the exclusion of some beneficiary groups. And in Uttarakhand, discrepancies in paperwork have led to issues in data collection and phone configuration.

Other than the challenges noted in the NITI Aayog’s report, there are additional challenges that lie in the path of bridging the gap in monitoring and supervision via ICDS-CAS. A paper published by Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) India at the Institute for Financial Management and Research (IFMR) in 2019, highlights the classic problem of misaligned incentives problem. Since those who are collecting data are also responsible for delivering services and affecting outcomes, this conflict of interest disincentivizes accurate data reporting, and primarily arises from the enormous pressure on states to present a favourable picture of nutrition in their jurisdiction. This pressure gets transferred to middle-level officials and finally trickles down to Anganwadi workers. In their dual role as data collectors and last-mile service providers, Anganwadi workers hold the power to ‘generate’ evidence that speaks well of their performance.

In a 2019 report, The Hindu Center for Politics & Public Policy highlights that as of date, there are no assessments of how the ICDS-CAS system has worked in practice and whether it has enabled those at the field and supervisory levels to get a firm grip on the actual malnutrition situation at the Anganwadi level, enabling early remedial action.