UN Climate Change recently published an update to the synthesis of climate action plans as communicated in countries’ NDCs. The Synthesis Report was requested by Parties to the Paris Agreement to assist them in assessing the progress of climate action ahead of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) this November in Glasgow, Scotland. Here is a review.

The abundance of heat-trapping greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere once again reached a new high in 2020, with the annual rate of increase above the 2011-2020 average. According to the World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO), Greenhouse Gas Bulletin, the above trend has continued in 2021.

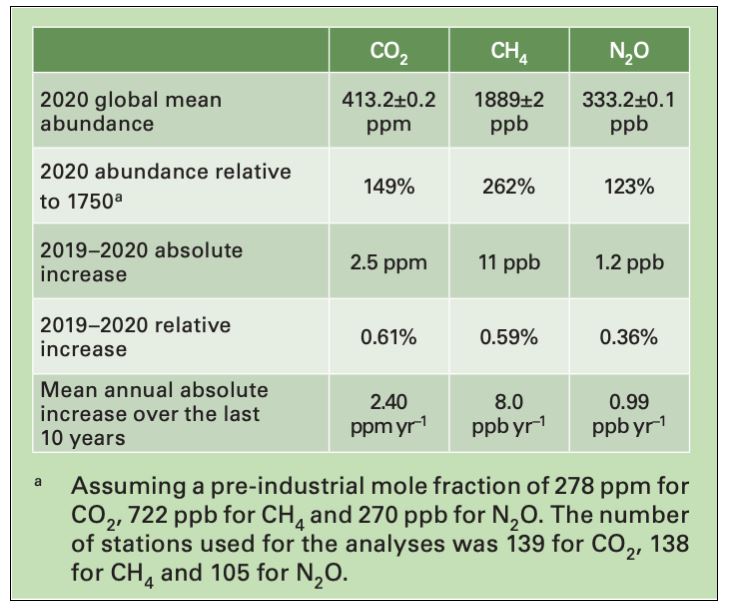

The 17th annual WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin reports atmospheric abundances and rates of change of the most important Long-lived GHGs (LLGHGs) – CO2 (Carbon Dioxide), CH4 (Methane) and N2O (Nitrogen Dioxide) – and provides a summary of other GHG contributions. Those three, together with dichlorodifluoromethane (CFC-12) and trichlorofluoromethane (CFC-11), account for approximately 96% of radiative forcing due to long-lived greenhouse gases (LLGHGs).

The globally averaged surface mole fractions for CO2, CH4, and N2O reached new highs in 2020. These values constitute, respectively, 149%, 262% and 123% of pre-industrial (before 1750) levels. The increase in CO2 from 2019 to 2020 was slightly lower than that observed from 2018 to 2019 but higher than the average annual growth rate over the last decade. This is despite the approximately 5.6% drop in fossil fuel CO2 emissions in 2020 due to restrictions related to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

For CH4, the increase from 2019 to 2020 was higher than that observed from 2018 to 2019 and also higher than the average annual growth rate over the last decade. For N2O, the increase from 2019 to 2020 was higher than that observed from 2018 to 2019 and also higher than the average annual growth rate over the past 10 years.

Message to Climate Change Negotiators at COP26 – the need for enhanced commitments.

The Greenhouse Gas Bulletin contains a stark, scientific message for climate change negotiators at COP26. At the current rate of increase in greenhouse gas concentrations, we will see a temperature increase by the end of this century far in excess of the Paris Agreement targets of 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

The report highlights that the economic slowdown from COVID-19 did not have any discernible impact on the atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases and their growth rates, although there was a temporary decline in new emissions. Many countries are now setting carbon neutral targets and it is hoped that COP26 will see a dramatic increase in commitments.

Radiative forcing (warming effect on climate) increased by 47%.

Radiative forcing is the change in energy flux in the atmosphere caused by natural or anthropogenic factors of climate change (measured by watts/metre²). It is a scientific concept used to quantify and compare the external drivers of change to Earth’s energy balance.

The GHG Bulletin shows that from 1990 to 2020, radiative forcing – the warming effect on our climate – by LLGHGs increased by 47%, with CO2 accounting for about 80% of this increase, based on monitoring by World Metrological Organisation’s Global Atmosphere Watch network.

As long as emissions continue, global temperature will continue to rise. Given the long life of CO2, the temperature level already observed will persist for several decades (even if emissions are rapidly reduced to net zero). Alongside rising temperatures, this means more weather extremes including intense heat and rainfall, ice melt, sea-level rise, and ocean acidification, accompanied by far-reaching socioeconomic impacts.

Changes in airborne fraction due to erratic climate events.

The GHG bulletin explains that roughly half of the CO2 emitted by human activities today remains in the atmosphere. The rest is absorbed by oceans and land ecosystems. The fraction of emissions remaining in the atmosphere, called airborne fraction (AF), is an important indicator of the balance between sources and sinks.

Changes in AF will have strong implications for reaching the goal of the Paris Agreement, namely, to limit global warming to well below 2° C, and will require adjustments in the timing and/or size of the emission reduction commitments.

Ongoing climate change and related events, such as more frequent droughts and the connected increased occurrence and intensification of wildfires, might reduce CO2 uptake by land ecosystems. Ocean uptake might also be reduced as a result of higher sea-surface temperatures, decreased pH due to CO2 uptake and the slowing of the meridional overturning circulation due to increased melting of sea ice.

Timely and accurate information on changes in AF is critical to detecting future changes in the source/sink balance. This information is available from observations of atmospheric CO2 made at key locations around the world from the WMO Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) Programme and its contributing networks. These long-term and accurate observations give direct insight into the trend in atmospheric levels of CO2 and other GHGs.

In order to better support GHG management policies through analysis of natural sinks and fossil fuel emissions, and to narrow them down to the regional or the local level, improved sustainability of the current in situ network and additional in situ data are needed.

The GHG bulletin argues that this goes hand in hand with increasing remote sensing capacities, especially in currently under-sampled regions, such as Africa and other tropical regions.

Updated NDCs indicate a projected GHG decrease of 12% in 2030, many countries indicate goals of carbon neutrality.

Under Article 4, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement, each Party is to prepare, communicate and maintain successive Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that it intends to achieve. UN Climate Change recently published an update to the synthesis of climate action plans as communicated in countries’ NDCs.

The Synthesis Report was requested by Parties to the Paris Agreement to assist them in assessing the progress of climate action ahead of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) this November in Glasgow, Scotland.

For the group of 113 Parties with new or updated NDCs, greenhouse gas emissions are projected to decrease by 12% in 2030 compared to 2010. This is an important step towards the reductions identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which estimated that limiting global average temperature increases to 1.5 degrees C requires a reduction of CO2 emissions of 45% in 2030 or a 25% reduction by 2030 to limit warming to 2 degrees C. If emissions are not reduced by 2030, they will need to be substantially reduced thereafter to compensate for the slow start on the path to net-zero emissions, but likely at a higher cost.

Within the group of 113 Parties, 70 countries indicated carbon neutrality goals around the middle of the century. This goal could lead to even greater emissions reductions, of about 26% by 2030 compared to 2010.

The update report synthesizes information from the 165 latest available NDCs, representing all 192 Parties to the Paris Agreement. The key findings of the NDC Synthesis Report confirm the overall trends:

- All Parties provided information on mitigation targets or mitigation co-benefits resulting from adaptation actions and/or economic diversification plans. The mitigation targets range from economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets to strategies, plans and actions for low-emission development.

- Most Parties communicated economy-wide targets, covering all or almost all sectors defined in the 2006 IPCC Guidelines, with an increasing number of Parties moving to absolute emission reduction targets in their new or updated NDCs.

- In terms of GHGs, almost all NDCs cover CO2 emissions, most cover CH4 and N2O emissions, many cover HFC emissions and some cover PFC, SF6 and/or NF3 emissions.

- Some Parties provided information on long-term mitigation visions, strategies, and targets for up to and beyond 2050, referring to climate neutrality, carbon neutrality, GHG neutrality, or net-zero emissions.

- Many Parties highlighted policy coherence and synergies between their domestic mitigation measures and development priorities, which include the SDGs, and for some that communicated new or updated NDCs, LT-LEDS (long-term low-emission development strategies) and green recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

NDC commitments focus on the transition to renewable energy, energy efficiency, gender mainstreaming, the role of local communities, etc.

The Synthesis Report reveals that renewable energy generation and shifting to low- or zero-carbon fuels were frequently indicated as being relevant to reducing the carbon intensity of electricity and other fuels, including by increasing the electrification rate of the supply and electrifying end-use of energy.

Across all priority mitigation areas, Parties frequently indicated waste-to-energy, improved management of manure and herds, and fluorinated gas substitution as key mitigation options relevant to reducing non-CO2 emissions. Parties often linked measures to the concept of circular economy, including reducing and recycling waste. Carbon pricing was frequently identified as efficiently incentivizing low-carbon behaviours and technologies by putting a price on GHG emissions.

Many Parties identified certain types of technology that they intend to use for implementing adaptation and mitigation actions, such as energy-efficient appliances, renewable energy technologies, low- or zero-emission vehicles, blended fuel, and climate-smart agriculture. Further, the main areas of technology needs mentioned by Parties were energy, agriculture, water, waste, transport, and climate observation and early warning.

Most Parties identified capacity-building as a pre-requisite for NDC implementation. Capacity-building needs for formulating policy, integrating mitigation and adaptation into sectoral planning processes, accessing finance, and providing the information necessary for clarity, transparency and understanding of NDCs were identified. In the new or updated NDCs, compared with their previous NDCs, more Parties expressed capacity-building needs for adaptation.

Some Parties referred to the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in their new or updated NDCs. The longer-term effects of the related changes in national and global GHG emissions will depend on the duration of the pandemic and the nature and scale of recovery measures.

Parties are increasingly recognizing gender integration as a means to enhance the ambition and effectiveness of their climate action. Most Parties provided information related to gender in their NDCs and some included information on how gender had been or was planned to be mainstreamed in NDC implementation.

Some Parties described the role of local communities and the role, situation, and rights of indigenous peoples in the context of their NDCs, describing the importance of drawing on indigenous and local knowledge to strengthen climate efforts, and arrangements to enable greater participation in and contributions to climate action by indigenous peoples.

India is on course to achieving its voluntary goals.

India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) document highlights that the country has been an active and constructive participant in the search for climate solutions. Even now, when the per capita emissions of many developed countries vary between 7 to 15 metric tonnes, the per capita emissions in India were only about 1.56 metric tonnes in 2010.

In recognition of the growing problem of climate change, India declared a voluntary goal of reducing the emissions intensity of its GDP by 20–25% by 2020, over 2005 levels, despite having no binding mitigation obligations as per the Convention. A slew of policy measures was launched to achieve this goal.

As a result, the emission intensity of our GDP has decreased by 12% between 2005 and 2010, as the documents highlight. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in its Emission Gap Report 2014 has recognized India as one of the countries on course to achieving its voluntary goal.

India’s NDCs promise 40% non-fossil fuel-based energy resources and carbon sink for 3 billion tonnes of CO2 by 2030

India is running one of the largest renewable capacity expansion programs in the world. Between 2002 and 2015, the share of renewable grid capacity has increased over 6 times, from 2% (3.9 GW) to around 13% (36 GW). This momentum of a tenfold increase in the previous decade is to be significantly scaled up with the aim to achieve 175 GW renewable energy capacity in the next few years. India has also decided to anchor a global solar alliance, InSPA (International Agency for Solar Policy & Application), of all countries located between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn.

With the goal of reducing the energy intensity of the Indian economy, the Ministry of Power through the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) has initiated a number of energy efficiency initiatives. The National Mission for Enhanced Energy Efficiency (NMEEE) aims to strengthen the market for energy efficiency by creating a conducive regulatory and policy regime. It seeks to upscale the efforts to unlock the market for energy efficiency and help achieve total avoided capacity addition of 19,598 MW and fuel savings of around 23 million tonnes per year at its full implementation stage.

The programmes under this mission have resulted in an avoided generation capacity addition of about 10,000 MW between 2005 and 2012 with the government targeting to save 10% of current energy consumption by the year 2018-19.

Keeping in view its development agenda, particularly the eradication of poverty coupled with its commitment to following the low carbon path to progress, India communicates the following as its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC):

- To put forward and further propagate a healthy and sustainable way of living based on traditions and values of conservation and moderation.

- To adopt a climate-friendly and cleaner path than the one followed hitherto by others at a corresponding level of economic development.

- To reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33 to 35% by 2030 from the 2005 level.

- To achieve about 40% cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030 with the help of the transfer of technology and low-cost international finance including from Green Climate Fund (GCF).

- To create an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover by 2030.

- To better adapt to climate change by enhancing investments in development programmes in sectors vulnerable to climate change, particularly agriculture, water resources, the Himalayan region, coastal regions, health, and disaster management.

- To mobilize domestic and new & additional funds from developed countries to implement the above mitigation and adaptation actions in view of the resource required and the resource gap.

- To build capacities, create a domestic framework and international architecture for quick diffusion of cutting-edge climate technology in India and for joint collaborative R&D for such future technologies.

Featured Image: Global Climate Change Targets