A recent study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science titled presents some important findings about the diversity of food culture prevalent in the Indus Valley Civilization. What are those findings? Here is a review.

A recent study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science titled ‘Lipid residues in pottery from the Indus Civilisation in northwest India’ on 9th December 2020 presents some important findings of the diversity of food culture prevalent in the Indus Valley Civilisation. In this article, we will briefly look at the history of the Indus Valley Civilisation and the salient features of this study. We will also discuss the context given by previous and current studies.

About the civilisation

The Indus Civilisation (c.3300 – 1300 BC) was one of the first complex civilizations, spread across large parts of modern Pakistan, northwest and western India, and Afghanistan. It extended from the Siwaliks in the north to the Arabian Sea in the South, and from the Makran coast of Baluchistan in the west to Meerut in the north-east. The area accounted for about 1,299,600 sq. km which is larger than ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. As R.S. Sharma puts it in this book ‘India’s Ancient Past’, ‘No other culture zone in the third and second millennia BC in the world was as widespread as the Harappa.’

Indus settlements were in diverse habitats and environmental contexts, including alluvial plains, foothills, deserts, scrubland, and coastal regions. Between c.2600 – 1900 BC (Mature Harappan or urban period), five Indus Civilisation settlements developed into sizable cities, with a range of other medium-sized urban settlements, small settlements with specialised craft production/and or fortifications, and rural settlements. Indus cities had multiple walled areas, segregated spaces, as well as large public structures, which included mud-brick platforms, granary, streets, citadel, and drains. The urban period is best known for its iconic material culture such as beads, bangles, standardised weights, and stamp steatite seals.

Details of study methodology

A great diversity of food traditions exists across South Asia, and the social role of food in the subcontinent is well-recognized. The authors highlight that the investigations into the archaeology of food from prehistoric contexts are in a relatively nascent stage.

The study deploys “ceramic lipid residue analysis” as it provides a powerful means by which the foodways of populations can be examined. It has been used in a range of archaeological contexts around the world to extract and identify foodstuff within ancient vessels. Organic residue analysis also provides a new understanding of vessel specialisation and use.

The article provides a background of the previous studies that have been conducted for the region using the same method. Until recently, only a single pottery sherd from South Asia had been studied via lipid residue analysis. More recently, a study investigated ceramic lipid residues from 59 vessels from a single site in Gujarat. The current paper presents the results of a much larger corpus of ceramic lipid residues across multiple Indus Civilisation sites in northwest India to investigate broader patterns of food consumption and vessel use. The results obtained are contextualised with existing archaeobotanical, zooarchaeological, and isotopic evidence to have a fuller understanding of the culinary strategies adopted by the Indus settlements in question.

Details of the study sites

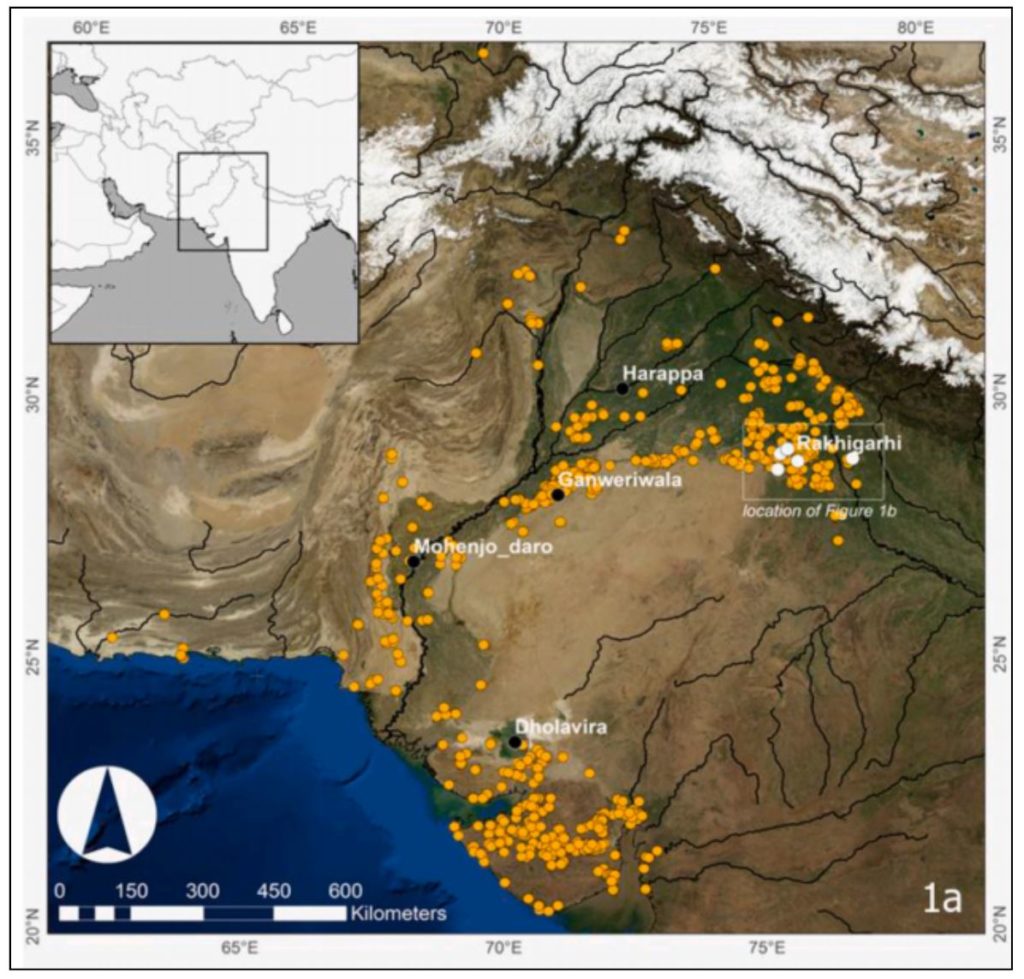

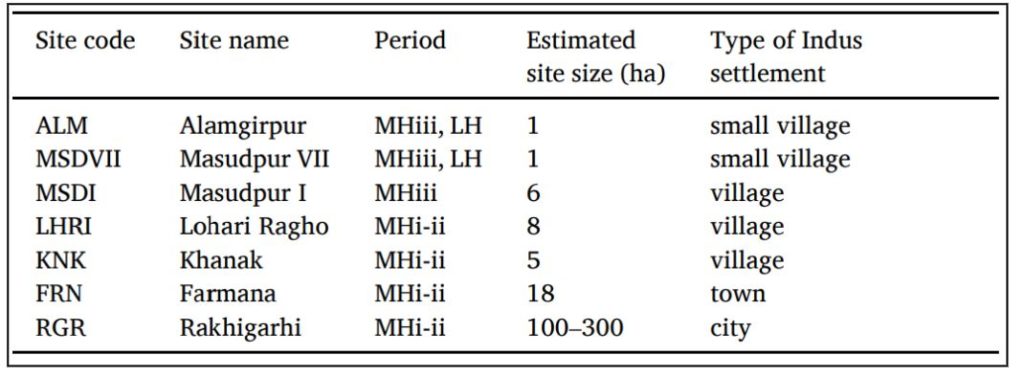

In this study, organic residues in pottery from one city, one town, and five rural settlements in northwest India are investigated to characterise any possible similarities or differences in foodstuffs used in vessels by urban and rural populations in a single region. The following figure depicts the extent of Indus settlements in the urban period with cities in black and study sites in white and other small- and medium-sized settlements are presented in yellow.

The study sites lie on the semi-arid alluvial plains of northwest India also referred to as the ‘eastern domain’ of the Indus Civilisation. The generally accepted chronological divisions of Mature Harappan (or Harappa phase c.2600/2500–1900 BC) and Late Harappan (c.1900–1300 BC) are used in this paper. Following are the details of each site.

Most of the vessels in this study belong to ‘Haryana Harappan’ pottery (Sothi-Siswal/ Non-Harappan pottery) and the rest is ‘Classical Harappan’. Haryana Harappan pottery comprise a red fabric of medium texture and few inclusions with great variety in techniques and decoration. There are several regional styles of pottery that were in use during the Indus Civilisation, which are considered the ‘Classical Harappan’ or ‘Red Harappan Ware’. They dominated in the large settlements of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. There are many overlaps between ‘Haryana Harappan’ and ‘Classic Harappan’ forms, such as perforated jars, ‘cooking vessels’, and dish-on-stands, etc. In this study, the vessel forms analysed included jars of varying sizes, ledged jars, necked jars, perforated vessels, and bowls.

The analysis was conducted on 172 pottery fragments recovered from rural and urban settlements. Pottery fragments were generally selected from contexts that had radiocarbon dates associated with them, and/or from contexts that were indicative of occupational surfaces. Rims of vessels were preferentially selected as experimental evidence suggests that the boiling of products in vessels would lead to lipids accumulating here.

Findings of the study

1. Diversity and variations in crops

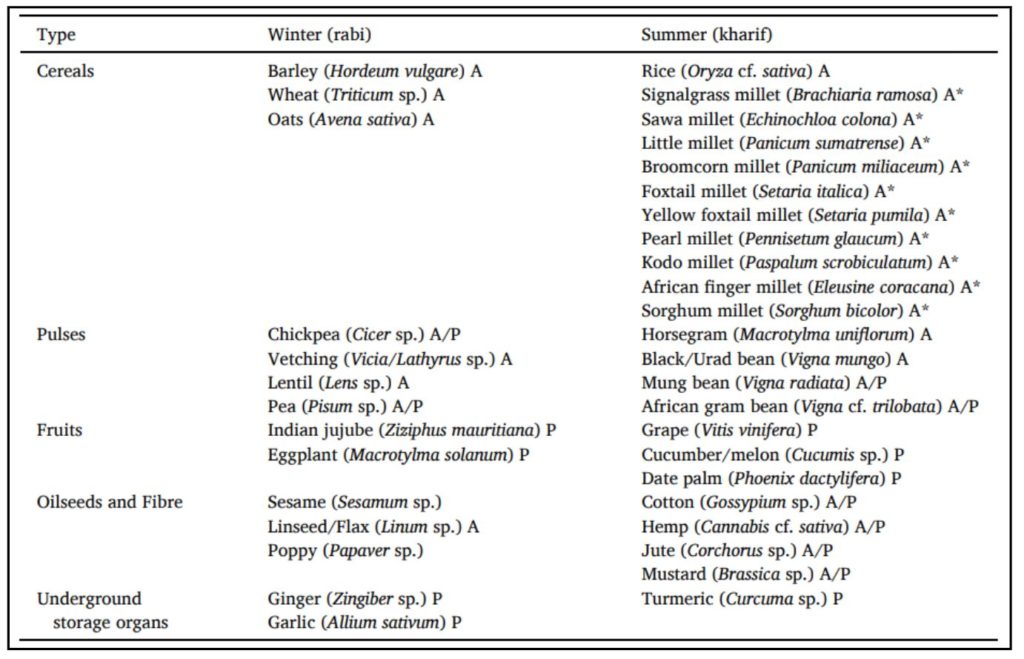

There is clear evidence of the diversity of plant products and regional variation in cropping practices. In the study region, both summer- and winter-based cropping was practiced, with evidence of barley, wheat, rice (C3 crops), and millets (C4 crops). Apart from cereals, the archaeobotanical assemblage is extremely diverse, characterised by a range of winter and summer pulses, oilseeds, and fruits. A list of winter and summer crops found in the Indus Civilisation is given below. ‘A’ indicates annual, ‘P’ indicates perennial plant, and ‘A/P’ indicates a plant that can be either. All plants reported are C3 plants except millets, which are C4. The difference between C3 & C4 crops can be read here.

- The overall lipid profiles of vessel fragments from all sites suggest the presence of degraded animal fats such as dairy or carcass fats.

- Indus vessels also show association with dairy processing.

- Multi-functionality of vessels

Lipid profiles suggest the consistent use of animal products and the compound-specific isotopic results suggest the multi-functionality of vessels. Given the diversity of resources that were available to Indus populations, it is possible that vessels were used for both plant and animal products to create foodstuffs throughout their life-histories.

- A broad similarity in products is observed across both rural and urban sites, possibly indicating a degree of regional culinary unity.

- Use of perforated vessels

This study revealed intriguing new information about the use of perforated vessels. Perforated vessels have been used for identifying dairy activities archaeologically in European contexts and are comparable to modern cheese strainers used for draining and separating curds during the hard cheese-making process. A hard cheese-making tradition has not been documented in the study region so far. Dairy curds and yoghurt are prepared daily in modern households in the region, but the cloth is preferentially used in the straining process. Ethnographic research of dairy practices in modern Punjab has, however, described the use of perforated lids used for heat regulation during dairy production. Although not conclusive, these results are exciting and have implications for how the function of Indus perforated vessels is interpreted in future research.

Similar findings from previous studies

As established by previous studies, on average, about 80% of the faunal assemblage from various Indus sites belong to domestic animal species. The article lists out all the major studies and their relevant findings. Out of the domestic animals, cattle/buffalo are the most abundant, averaging between 50-60% of the animal bones found, with sheep/goat accounting for 10% of animal remains.

The high proportions of cattle bones may suggest a cultural preference for beef consumption across Indus populations, supplemented by the consumption of mutton/lamb. Pigs make up about 2–3% of total faunal assemblages across Indus sites but the domestic status of the pig is not yet determined. Wild animal species like deer, antelope, gazelle, hares, birds, and riverine/marine resources are also found in small proportions in the faunal assemblages of both rural and urban Indus sites, suggesting that these diverse resources had a place in the Indus diet.

Limitations of the study

One of the major factors affecting the study of ancient food in South Asia, particularly northwest India, is the degree of organic preservation at archaeological sites. The preservation of lipids is dependent on a range of environmental and cultural factors and lipid preservation cannot be reliably predicted. It is well-recognized that fluctuations in temperature and moisture, pH levels, and mineralisation negatively affect the preservation of organic material in South Asian archaeological sites. Thus, this study also tested the degree of preservation of lipids in pottery from sites in northwest India.

All the study sites have alkaline soils and experience seasonal, heavy rainfall and hot temperatures, and have been subject to major transformations in the recent past due to agricultural activity. The combination of these conditions likely creates an unfavourable environment for organic preservation, which is also reflected in the poor preservation of seeds and bones at these sites.

Studies have demonstrated how specific types of food processing in vessels, such as boiling or roasting, would lead to higher concentrations of lipid in specific parts of vessels. However, as different parts of the same vessel were not analysed in the current study, and overall lipid preservation was poor, it was not possible to make interpretations about the use of vessels for specific types of food-processing.

Featured Image: Indus Valley Civilisation