In this week’s review of the court judgements, we look at judgements of the Supreme Court in matters of Personal Liberty, corrupt practices in elections, fundamental rights to reside and settle, establish educational institutions, Delhi High Court’s decision on payment aggregators, and Bombay High Court’s decision on corruption.

Supreme Court: There can be no cavil in saying that lodging juveniles in adult prisons amounts to deprivation of their personal liberty on multiple aspects.

In Vinod Katara vs. State of Uttar Pradesh, the two-judge bench of the apex court held that in addition to freedom from physical restraint, liberty also includes those rights and privileges that have long been acknowledged as being necessary for the orderly pursuit of happiness by a free man. There can be no argument against the statement that keeping children in adult jails amounts to various forms of personal liberty infringement.

The apex court was hearing a writ petition filed by the petitioner regarding the status of juvenility. The petitioners and co-accused were found guilty of murder by the Sessions Court, Agra, which convicted and sentenced them to life imprisonment. On filing an appeal, the Allahabad High Court reaffirmed the judgement of the Sessions Court. Going against this, the petitioner filed Special Leave Petition (SLP) at the SC, which declined to entertain and eventually dismissed it. At that point, the claim for juvenility was not raised by the petitioner.

While hearing a PIL, the Allahabad High Court ordered the Juvenile Justice Boards to determine the age of prisoners in jails who claimed to be a juvenile. On medical examination of the applicant, it was found that the applicant could be around 15 years of age during the commission of offence. The Family Registrar Certificate also shows the age as 14 years. The court looked at the applicability of the provisions of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000, hereby referred to as the 2000 Act.

Upon looking at the judgements in Pratap Singh vs. State of Jharkhand & Anr, Bijender Singh vs. State of Haryana and Anr, the apex court concluded that according to Section 20 of the 2000 Act, if the accused was older than 16 but younger than 18 on the date of the incident, the court’s proceedings would proceed to their logical conclusion, with the exception that if the juvenile was found guilty, the court would not impose a sentence on him instead referring him to the Board for the proper orders under the 2000 Act.

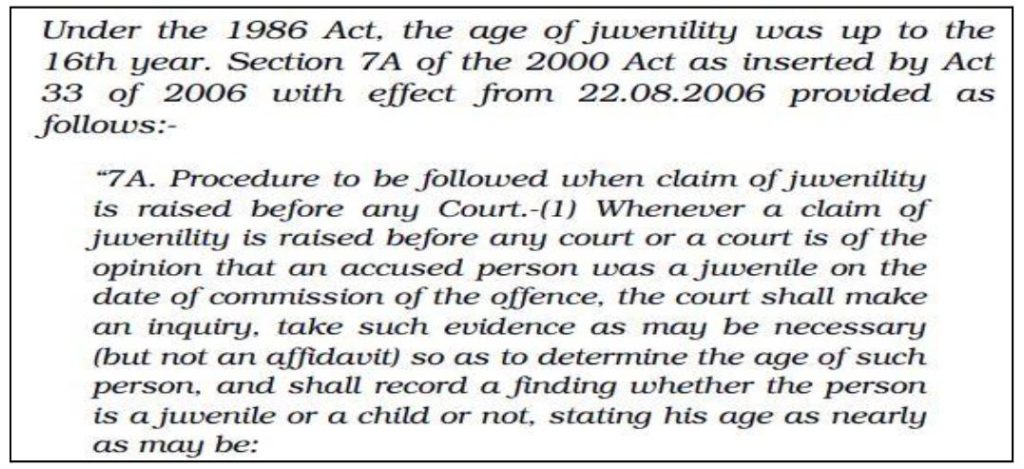

Section 7A of the act also talks about the procedure to be followed when such claims of juvenility are raised before any courts.

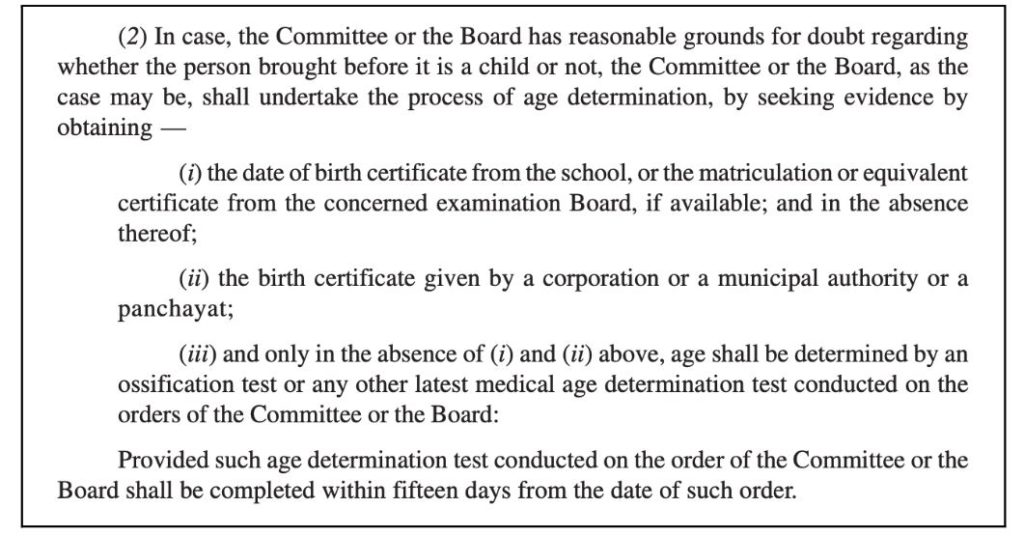

The apex court looked at the objectives of the Juvenile Justice Act (Care and protection of Children), 2015 to examine the plea of juvenility at later stages. It held that JJ Act is a beneficial legislation, and the goal is to promote the well-being of the juvenile, while maintaining the principle of proportionality, by which and under which the appropriateness of the response to the circumstances of both the offender and the offence, including the victim, should be protected. The court also looked at the procedure for determining the age of the juvenile (Section (94(2) of the above act).

In the absence of such documents owing to various reasons, and the request for a medical examination, keeping in mind the objectives of the legislation, the apex court directed the sessions court to conduct an Ossification test or any other modern age determining tests, and submit the report within one month of the issuance of the order.

Supreme Court: Irrespective of the impact of the false declaration about the assets of a candidate, or dependents on the election, it still amounts to corrupt practice.

In S. Rukmini Madegowda vs. The State Election Commission, the Supreme Court held that a false declaration about the assets of a candidate, his/her spouse, or other dependents, would amount to ‘corrupt practice’ and a hyper-technical view to omit any provision requiring disclosure of assets would be against public interest and the spirit of the Constitution.

The appellant filed her nomination as a councilor for a reserved seat in the elections of the Mysore Municipal Corporation, along with the declaration of assets. She went on to win the election. However, the unsuccessful candidate filed an election petition alleging her of falsely declaring the assets under sections 33 and 34 of the Karnataka Municipal Corporations Act, 1976, and thereby indulged in ‘corrupt practice’. The Trial court dismissed the petition, and when an appeal was filed in the High Court, the High Court directed the Trial Court to reconsideration the petition, owing to the apex court’s judgements in Association of Democratic Reforms vs. Union of India, and Lok Prahari vs. Union of India. Accordingly, the Trial Court allowed the petition and set aside the election. On filing an appeal at the High Court, the High Court dismissed the appeal.

The following issues were raised by the appellant in this petition.

- Whether a duly elected candidate, serving as the Mayor, of Mysore City Corporation after the election, could be unseated, in the absence of any statutory provision requiring disclosure of assets in the affidavit filed with the nomination form?

- Whether non-disclosure of assets would constitute corrupt practice, in the absence of any statutory provision requiring disclosure of assets?

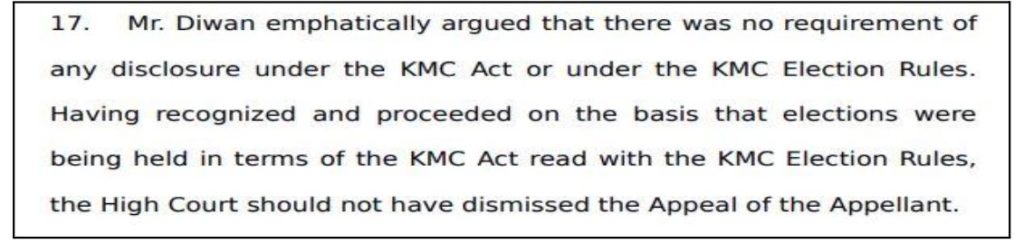

The appellant, through her counsel, argued that a candidate who intends to run for office cannot be compelled to disclose his or her spouse’s assets by the approval of a policy decision in the absence of a particular legal provision requiring such disclosure by way of affidavit.

The appellant referred to the judgements in Shrikant vs. Vasantrao & Ors, where it is held that an election petition is a legal action that must adhere to the statute that it is filed under or the Statutory Rules established by that law. The counsel also remarked the distinction between elections held in accordance with the KMC Act and/or the KMC Rules and elections managed by the Election Commission of India, and Rule 4A of the 1961 Rules cannot be imported to KMC rules in the absence of appropriate amendments to the rules.

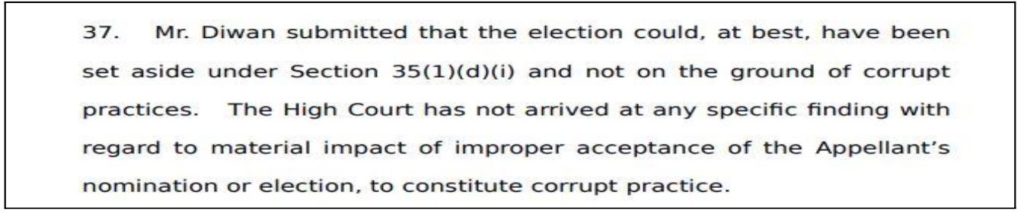

The Counsel further remarked that at the maximum, the election could be set aside under Section 35(1)(d)(i), and not under corrupt practice.

Upon hearing the counsel, the apex court looked at the provisions of the KMC act, 1976. It referred to Section 39, which mentions about ‘undue influence’ as a corrupt practice. The apex court looked at Section 123 of the RP Act,1951 which defines corrupt practices. In Lok Prahari case, the apex court held that non-disclosure would amount to ‘undue influence’ as defined under the Representation of People Act, 1951.

On the question of the powers of the Election Commission, the apex court reiterated that ‘Article 324 of the Indian Constitution is provided to take care of surprise situations and it operates in areas left unoccupied by legislation.’ Further, it held that it would be against the letter of the Constitution and the public interest to take a hyper-technical view of the omission to include any particular provision in the KMC Election Rules, similar to the 1961 Rules, specifically demanding the declaration of assets. Accordingly, the appeal was dismissed.

Supreme Court: There is only one domicile of the country and no separate domicile for a State, and State Reorganization laws cannot take away from citizens, the right to reside and settle in any part of the country

In The State of Telangana & Anr vs. B. Subba Rayudu and Others, the two-judge bench of the apex court held that the respondent has a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(e) to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India and any statute of the state cannot take away the right to reside & settle in any part of the country from the citizens.

The appellant, B. Subba Rayudu, held the State Cadre position of Joint Director Class A in the Animal Husbandry Department of the undivided State of Andhra Pradesh. His wife, B. Shanthabai was employed by the same state as an Assistant Registrar. Upon the bifurcation of the State under the Andhra Pradesh Reorganization Act, 2014, Rayudu selected Telangana as the choice of his allocation. He filed a request that he be treated as a local candidate of the State of Telangana but was instead provisionally assigned to the State of Andhra Pradesh. The High Court allowed the writ petitions and suggested the Tribunal consider them again. It also directed that he should not be relieved from his present place of posting till the disposal of the Interlocutory Application. Subsequently, in 2017, the Administrative Tribunal of the State was abolished, and the cases were transferred to the High Court of Telangana.

The counsel for the state argued that the respondent was a ‘local candidate’ of the State of Andhra Pradesh, and the final allocation is based on the first amongst those local candidates of the State, who had opted for the State in order of their seniority and thereafter, if allocable posts still remained, those posts were to be filled up in the order of seniority from amongst nonlocal candidates who had opted for the State.

The counsel for the petitioner argued about the limited nature of Article 136 of the Indian Constitution. They argued that the court was not bound to set aside the High Court’s decision.

Additionally, the petitioner argued that even though their birth is in Andhra Pradesh, he has been educated and resided for most of his life in Telangana, hence can be categorized as a ‘local candidate’ of Telangana. Agreeing with most of the points raised by the petitioner, the apex court held that:

On the question of the domicile of the petitioner, the apex court relied on Dr. Pradeep Jain vs. Union of India, and reiterated that there is only one domicile, i.e., domicile of the country and no separate domicile for the state exists.

Accordingly, the apex court reaffirmed the judgement of the High Court of Telangana & dismissed the petition.

Supreme Court: The right to establish an educational institution is a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution and reasonable restrictions on such a right can be imposed only by a law and not by an executive instruction

In Rajeev College of Pharmacy vs. Pharmacy Council of India, a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court held that executive instructions cannot impose restrictions on the fundamental right to establish an educational institution. The apex court was hearing an appeal petition filed by the Pharmacy Council of India (PCI) against the judgements of various High Courts allowing the writ petitions challenging the council’s resolution to put a moratorium on the establishment of new pharmacy colleges for a period of five years, beginning from 2020-21.

The Counsel for the appellant argued that PCI has the powers under the Pharmacy Act, 1948 to regulate pharmacy education, and the central council of PCI consists of experts from various fields, which makes it a competent authority to take decisions keeping in mind the quality of pharmacy education. The decision to impose a moratorium was taken after the recommendations of the sub-committee to prevent the mushrooming of the colleges. Additionally, the PCI had also consulted the Union Government before such a decision.

Further, the appellant argued that the power to regulate also includes the power to prohibit as held by the apex court in Madhya Bharat Cotton Association Ltd. vs. Union of India & Anr, and the Madras High Court in Star India Private Limited vs. Department of Industrial Policy. Expanding on it, the appellant argued that it is the duty of PCI to ensure the objectives of the Pharmacy Act, 1948 are fulfilled.

The counsel for the petitioners argued that the right to establish educational institutions is a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution, and is affirmed by the apex court in T.M.A. Pai Foundation & Ors vs. State of Karnataka & Ors. Additionally, they submit that reasonable restrictions could be imposed, but the burden lies on the state to establish the nexus between restrictions and the desired objective. The restrictions currently imposed are completely arbitrary and discriminatory. Further, on the power to restrict, the petitioner argued that,

The other counsels for petitioners argued on the limitations of statutory provisions on restricting the fundamental rights of citizens. These arguments were also upheld by the High Courts of Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, and Delhi.

Agreeing with the points raised by the petitioners, the apex court held that while there may be a necessity to impose restrictions to prevent mushrooming of colleges, it must be strictly done in accordance with the law, and just because the State’s Legislature has the jurisdiction to legislate on the subject covered by the executive order, the State or its officers cannot use their executive authority to violate citizens’ rights, as held by the five-judge Constitution Bench in State of Madhya Pradesh & Anr vs. Thakur Bharat Singh. Accordingly, the appeals are dismissed.

Bombay HC: A person for the charges of corruption under the Prevention of Corruption Act cannot be convicted on moral and ethics, instead it is mandatory to prove the demand & acceptance of bribe.

The High Court of Judicature at Bombay Bench at Aurangabad, in Sayaji Dashrath Kawade vs. The State of Maharashtra held that morals and ethics do not form the basis for conviction under the Prevention of Corruption Act 1988, and the proof of demand and acceptance of bribe is mandatory. It further held that when the statute provides for certain mandatory requirements for proving offence, no shortcuts are permitted.

The High Court was hearing an appeal petition filed against the judgment of the Special Court to investigate the corruption offences. The appellant was found in the possession of currency with anthracene powder, which is often used to trap the offenders. Accordingly, the Judge of the Special Court held the conviction and remanded the appellant to imprisonment and fine. Aggrieved with the judgement, the appellant approached the High Court.

The counsel for the petitioner held that mere recovery of the currency does not constitute offences under section 7, & section 13 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (PoCA, 1988).

And the presumption of corruption under Section 20 of the above Act can be raised only when such demand for a bribe can be proved under this act, which is not the scenario in the present case. The counsel relied on the judgements of the apex court in M.R.Purshotham vs. State of Karnataka, and State of Maharashtra vs. Dnyaneshwar Laxman Rao Wankhede.

The counsel for the State argued that the conscious possession of the currency notes itself demonstrates the acceptance of the bribe, and such acceptance can be used to assume presumption under section 20 of the PoCA, 1988. In addition, no satisfactory explanation about the possession of the tainted currency notes is offered by the appellant.

The High Court bench, on hearing the arguments by both sides, relied on the judgement of the apex court in M.R.Purshotham vs. State of Karnataka, whereby it is held that mere possession and recovery of currency notes from the accused do not constitute offence under Section 13(1)(d) read with Section 13(2) of the PoCA,1988 when the demand for such is not proved. Further, in B.Jayaraj vs. State of Andhra Pradesh, the apex court held that the demand for a bribe must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt, which is not the same in the present case.

Further, on the sanction order for prosecution against a public servant under the PoCA, 1988, application of mind by the sanctioning authority is important, and any such order of sanction of prosecution must demonstrate such proper application of mind. In the present case, it is evident that the authority had failed to apply for independent order before such sanction.

Accordingly, the Special Court order is quashed & the appellant is acquitted of the charges.

Delhi HC: The work function of the Payment Aggregators comes within the definition of a payment system, axiomatically, the power to issue guidelines for efficient management falls under RBI.

In Lotus Pay Solutions Pvt. Ltd. & Anr vs. Union of India & Ors, the Delhi High Court held that the Payment Aggregators, hereby referred to as PAs, fall under the ambit of the payment system under the Payments and Settlements Act, 2007, making RBI the nodal agency to issue guidelines for its efficient and effective management.

The High Court was hearing a writ petition filed by Lotus Pay Solutions Private Limited, seeking to quash three clauses of the RBI circular titled, ‘Guidelines on Regulation of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways’, published on 17 March 2020. The three contentious clauses raised by the petitioners are Clauses 3, 4, & 8. They deal with authorization, capital requirements & settlement and escrow account management respectively.

The petitioners argue that they perform the role of an intermediary, and the latest guidelines by the RBI extend way beyond the powers conferred on it by the 2007 Act. While section 18 of the act confers powers to RBI to issue directions, section 10(2) authorizes RBI to issue guidelines for the proper and efficient management of payment systems. Neither of these provide for mandating RBI’s authorization for the functioning of Payment Aggregators. The petitioners differentiate themselves as payment aggregators and not form of the payment system.

Further, clause 4 which sets conditions on the minimum capital requirements is unreasonable and arbitrary. It treats all the PAs and Payment Gateways (PGs) in a similar manner, which is not prudent. Having a monetary requirement that does not have a bearing on the performance and functions of the PAs would eventually suppress innovation. The RBI’s discussion paper in 2019 makes it clear about the no-complaint performance of intermediaries in the last decade, making the latest guidelines unnecessary. On clause 8, the petitioners argue that it exposes them to operational risks, causing financial instability. It ignores that the PAs are functioning smoothly currently.

The RBI, on its part, submitted that the definition of the phrase “payment system” as stated in section 2(1)(i) of the 2007 Act applies to the job of the PA, which, in essence, requires it to receive money from the payer and allow its return to the beneficiary. According to Section 3 of the 2007 Act, RBI has been recognised as the “designated authority” for governing and overseeing payment systems. Since Section 4 of the 2007 Act specifically states that RBI is the sole party authorised to start or operate a payment system, non-bank PAs like the petitioner can only continue their operations provided they are authorised and follow the 2020 guidelines. On the scope of judicial review, it submitted that,

The court, upon hearing both sides held that PAs fall within the ambit of the payment system, thereby making RBI the responsible agency to supervise the payment system in India. The court also held that nothing untenable can be found in clause 8 of the guidelines.

Accordingly, the writ petition was dismissed.

Featured Image: Court judgements