In this edition of court judgements, we look at the Supreme Court’s judgement on interference of High Courts in acquitting a trial court order, Delhi High Court’s judgement on mental cruelty by wife by leaving matrimonial home repeatedly, Karnataka High Court’s judgement on compassionate appointments, Bombay High Court’s judgement on voluntary abandonment of employment and Telangana High Court’s judgement waiving off the 1-year cooling period for dissolution of marriage.

Supreme Court: Unless the finding of acquittal is found to be perverse or impossible, interference with the same is not permissible by the appellate court.

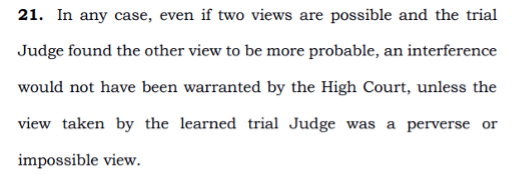

In Ballu @ Balram @ Balmukund and Another vs. The State of Madhya Pradesh, the apex court held that interference against the acquittal would not have been warranted by the High Court unless the view taken by the trial Judge was a perverse or impossible view.

The two-judge bench of the apex court comprising Justice B.R. Gavai and Justice Sandeep Mehta, was hearing an appeal against the Madhya Pradesh High Court’s judgement that overturned the acquittal of the accused. The brief facts of the case are as follows: The deceased Mahesh Sahu was in a relationship with a girl named Anita, who is the sister of one of the accused and the daughter of the other accused. Both Mahesh Sahu and Anita resided in Agra for a couple of months, thereafter which Anita returned and got married to another person. Post-marriage, Anita was in contact with Mahesh Sahu. Due to this enmity, the appellants (mother and son) caused the death of the deceased in furtherance of their common intention. The trial court acquitted the accused persons since the prosecution has failed to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt. Upon appeal, this order was reversed by the High Court, which sentenced the accused. The current case is against the judgement of the High Court.

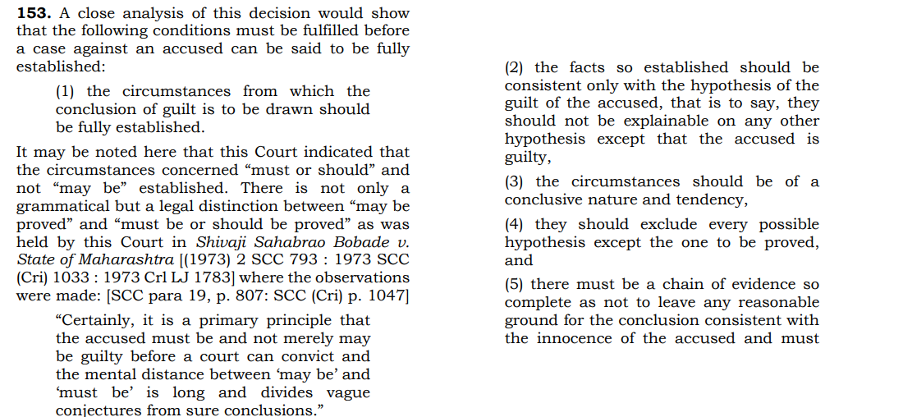

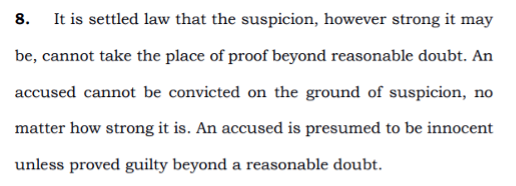

The counsel for the appellant argued that the High Court erred in reversing the well-reasoned judgment of acquittal, whereas the counsel for the state argued that the trial court judge misread the evidence, thereby arriving at a wrong conclusion. Upon hearing both sides, the court remarked that the prosecution case rests on circumstantial evidence. The apex court looked at the judgement in Sharad Birdhi chand Sarda vs. State of Maharashtra, in which golden principles regarding conviction on the basis of circumstantial evidence are crystallized as follows.

Further, in cases of circumstantial evidence, the court remarked that it’s really important that before someone is declared guilty and punished, there should be clear and strong evidence proving they actually did the crime. It’s not enough that they might have done it; there must be solid evidence showing beyond doubt that they’re responsible. This evidence should be so convincing that there’s no other reasonable explanation except that the accused did it.

Looking at the findings of the trial court and order of the High Court, the Apex court remarked that the High Court overturned a well-reasoned judgment from the trial court that was based on a correct understanding of the evidence, solely relying on conjectures and surmises. Even though the High Court mentioned the legal guidelines set by this Court regarding when it can overturn a decision of acquittal on appeal, it had completely misapplied those guidelines.

Accordingly, the Judgement of the High Court is quashed and set aside.

Delhi HC: Withdrawal from a marital relationship from time to time, without any fault on the part of the spouse, amounts to mental cruelty.

In X vs. Y, the Delhi High Court held that prolonged periods of continuous separation by the wife without any fault of the husband amounts to mental cruelty.

The Division bench of the Delhi High Court comprising Justice Suresh Kumar Kait and Justice Neena Bansal Krishna was hearing an appeal against the order of the Family Court that rejected the petition for divorce by the husband. The brief facts of the case are as follows: The appellant husband and the respondent got married in 1992 and had a son and a daughter. Over the course of about 19 years, they lived together until they eventually separated. The husband stated that the respondent had an intemperate and volatile personality and had subjected them to various forms of cruelty. The husband also claimed that the respondent left them on at least seven occasions, including the last and final time. Aggrieved by this, the husband filed the petition for divorce on grounds of desertion and cruelty.

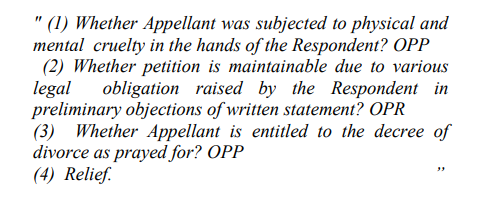

The wife responded that she suffered humiliation by her mother-in-law and the appellant always acted on the advice and instigation of her mother-in-law. The family court, based on these arguments, framed three issues.

Upon careful examination of each incident of isolation, the trial court judge held that there was no cruelty committed by the wife and it is rather the husband whose conduct shows reasonable cause for the respondent to have left the matrimonial home. Accordingly, the divorce petition was dismissed. The present appeal is against this order.

The High Court, relying on the Samar Ghosh vs. Jaya Ghosh, held that long periods of continuous separation could lead to an irreparable breakdown of marriage, constituting mental cruelty and cessation or deprivation of cohabitation and conjugal relationships, which is an act of extreme cruelty. Further, the court remarked that the entire chain of evidence suggests that the respondent left the matrimonial home, from time to time, without there being any act or fault on the part of the appellant. Such withdrawal by the respondent from time to time, are acts of mental cruelty to which the appellant was subjected, without any reason or justification.

Furthermore, the High Court, based on multiple apex court judgements, remarked that while looking at the acts of mental cruelty, the court must look at married life as a whole and not merely at a few isolated incidents.

The High Court held that it is a case of mental agony to the appellant entitling him to a divorce, on the ground of cruelty under S. 13(1)(ia) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Since the period of desertion is reflective of an intent of abandonment and rejection of matrimonial relationship, the essential ingredients in proving the grounds for desertion, the appellant is entitled to divorce on grounds of desertion too.

Accordingly, the High Court set aside the order of the Family Court and the husband was granted the divorce on grounds of cruelty and desertion.

Karnataka HC: Compassionate appointment cannot be sought as a matter of right and against a particular post.

In Smt. K. C. Nagalambike and Ors. vs. The Managing Director KSRTC & Ors, the Karnataka High Court held that though the purpose and object of compassionate appointment are to overcome the financial difficulty by the sudden demise of a breadwinner, they cannot be sought as a matter of right and against a particular post.

The single-judge bench comprising Justice S.G. Pandit was hearing a petition to issue a writ of mandamus to consider appointment to eligible posts under compassionate grounds. The brief facts of the case are as follows: The father of the petitioner, S. Guruswamy, was working as a senior driver and passed away while on duty on 10 September 2011. After his death, being a qualified Civil Engineering graduate, the petitioner applied for the position of Junior Engineer (Civil) on compassionate grounds.

Initially, they were told there were no vacancies for the Junior Engineer (Civil) position, and their names would be put on a waiting list for compassionate appointments. Later, the Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC) decided not to make compassionate appointments to Grade-III Supervisory Posts. On 5 September 2018, the petitioners were asked to apply for the post of Junior Assistant-cum-Data Entry Operator if they were interested. They were also given other options, like a Grade-III Security Guard position, but the petitioner declined this offer.

The counsel for the petitioner argues that his case should be considered for compassionate appointment according to the scheme that was in place at the time of his father’s death in 2011. They claim that the scheme allowed for appointments to Supervisory Posts and Junior Engineer positions, and since the second petitioner was a qualified Civil Engineering graduate, he should be considered for the Junior Engineer position. They argued that not considering his case goes against the scheme and is discriminatory.

The counsel for the corporation argued that a person cannot seek compassionate appointments as a matter of right and against a particular post. Further, the purpose of providing a compassionate appointment would be defeated if the petitioner is provided a compassionate appointment after more than ten years.

After hearing both sides, the Karnataka High Court’s single-judge bench stated that the petitioner wasn’t entitled to any relief. The court emphasized that compassionate appointments aim to help financially after a sudden death, and if there was a real need for employment, the petitioner wouldn’t have rejected the Grade-III Security Guard or Junior Assistant-cum-Data Entry Operator positions. Additionally, when the petitioners are able to survive without compassionate appointment for more than a decade, it means, they may not require appointment much less for compassionate appointment.

Bombay HC: Voluntary abandonment of employment cannot be accepted on account of the absence of a notice on calling upon to join duties.

In M/s. Premsons Trading (P) Ltd vs. Dinesh Chandeshwar, the Bombay High Court held that it is a well-settled law that to prove voluntary abandonment of employment, there must be a notice directing to resume duties. In the absence of any such notice, the voluntary abandonment of employment cannot be accepted.

The single-judge bench headed by Justice Sandeep V. Marne was hearing a petition challenging the award passed by the Presiding Officer, Second Labour Court, Mumbai. The brief facts of the case are as follows: The petitioner is a private company involved in trading. The respondent began working for them in August 1988 as a Counter-Boy at a retail store called ‘Premsons’ in Mumbai. Later in November 2001, he was transferred to another company within the same group as a Dispatch Incharge in the Crockery Department. In January 2005, he was moved to the petitioner’s warehouses in Sewree and Wadia House, Cotton Green. The respondent claims he worked until 12 February 2013, when his services were terminated by one of the directors without proper procedure.

The respondent requested leave from 10 February 2013 to 15 March 2013, which was approved by one director but opposed by another, leading to the termination of his services. The respondent claims he worked until 12 February 2013, when his services were terminated by one of the directors without proper procedure. The respondent tried to resolve the issue through the Deputy Labour Commissioner, but since the petitioner didn’t cooperate, the case went to the Labour Court. Witnesses were examined by both parties before the Labour Court, which eventually ruled in favour of the respondent, directing the petitioner to reinstate him with back wages from 12 February 2013. The current case is against this award.

After hearing both sides, the court remarked that though the respondent attempted to join services, the petitioner was no longer permitting the respondent to work. Further, the claim of voluntary abandonment of employment cannot be accepted if there is no notice directing to resume duties.

Accordingly, the High Court, considering the unsavoury relationship between the parties, awarded for lumpsum of Rs. 8 Lakh in lieu of reinstatement and back wages within six weeks would be the appropriate remedy, instead of reinstating and full back wages as awarded by Labour court. The petition stands disposed of.

Telangana HC: Grants waiver of mandatory waiting period of one year for divorce.

In Dandamudi Phani Krishna vs. Boyapati Lakshmi Aparna, the Telangana High Court granted the waiver of the mandatory period of one year for divorce, considering the exceptional hardships faced by the couple.

The Single judge bench headed by Justice P. Sam Koshy was hearing a plea against the order of the Family Court that declined their divorce petition since the petition was filed within one year of marriage. The couple approached the High Court for the waiver of the one-year waiting period. The brief facts of the case are as follows: The petitioners got married on 1 June 2023. They lived together for a few months, but then they started having problems due to health issues and impotency. Despite discussing their issues, they both don’t want to continue their marriage. They went to the Family Court to get a divorce, but their petition was rejected because they filed it within one year of marriage. The petitioners argue that the Family Court made a mistake in rejecting their petition and didn’t consider their health problems and impotency.

The counsel for the petitioners also relied on the apex court judgement in Amardeep Singh vs. Harveen Kaur, wherein the court held that time period under Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 is directory and is open for courts to use their discretion in a case-to-case basis.

The counsel for petitioners also relied on multiple judgements of various High Courts that waived off the cooling period of one year in cases of exceptional hardships. The court looked at the situational hardships faced by the couple. It also noted that the couple already waited for ten months, and they only had two more months left to complete the waiting period required for divorce. So, they’ve already waited for a significant portion of the required time. Adding to the situation is the fact that the petitioner, who is forty years old, has received marriage proposals and wants to remarry. She’s concerned about the risks associated with pregnancy at her age, like a higher chance of miscarriage and complications during delivery. She wants to remarry soon to reduce these risks. Their decision to divorce is mainly because their health problems and impotency have made it too difficult for them to maintain their relationship. They both agree that there’s no chance of reconciliation, showing that their marriage has irretrievably broken down.

The High Court opined that it acknowledges the importance of exercising its discretion wisely, as outlined in Section 14 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. This law empowers the Court to waive the obligatory one-year waiting period in cases of exceptional hardship, which is clearly evident in this particular case.

Accordingly, the order of the Family Court is set aside, and the petitioners are granted a petition under section 14 (1) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.