COVID-19 has once again reminded us of the importance of a strong public health system. India has poor public health infrastructure right from the grass root level. Here is an analysis of the infrastructure at PHCs across the country.

India has now at the fourth position in the list of worst hit countries by COVID-19. The number of cases has crossed 3 lakh. As the number of cases continues to increase, the public health system in the country is put to test. Questions are being raised in multiple states about the adequacy of facilities in our hospitals. Since public health facilities alone cannot handle the load of patients, private hospitals are also taking in COVID-19 patients in many states. States like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have considered capping the cost of treatment in private hospitals to prevent exploitation.

The flipside of this focus on COVID-19 meant that prevention and treatment of non-communicable diseases have been severely disrupted around the world, according to a WHO survey. People suffering from other non-communicable diseases are at a greater risk because of comorbidity. But such people are reluctant to go hospitals fearing risk of contracting the virus. On the other hand, human and material resources are being diverted for the fight against COVID-19 across countries.

Public healthcare centres have been converted to dedicated COVID-19 facilities

According to WHO, primary healthcare plays an important role in differentiating patients with respiratory symptoms from those with COVID-19, making an early diagnosis, helping vulnerable people cope with their anxiety about the virus, and reducing the demand for hospital services. Earlier in May, the Government of India, converted some public health facilities across the country into dedicated COVID Hospitals, COVID Health Centres, and COVID Care Centres for COVID-19 management. Based on the severity of the infection in a person, they will be sent to either of these three.

Not only during a pandemic like this one, but Primary Healthcare Centres or PHCs act as linchpin in rural health services in India as they are the first point of contact between the community and a medical officer. PHCs are envisaged to provide integrated curative and preventive healthcare to rural population, which is a majority in India. There are three tiers of rural health institutions- Sub Health Centre, Primary Health Centre (PHCs), and Community Health Centre (CHCs).

Three tiers of rural public health institutions exist in India

As per the ‘Minimum Needs Program’ introduced during the Fifth Five Year Plan, one Sub Centre was to be established for a population of 5000 people in plains and for 3000 people in hilly and tribal areas. A PHC was to be established for 30,000 population in plains and 20,000 in tribal and hilly areas, and one CHC or Rural Hospital for a population of one Lakh. PHCs act as referral centres for around 6 Sub- Centres and CHCs act as referral centres for around 4 PHCs, for patients requiring specialized healthcare services.

Despite the prescribed standards on the availability of facilities in PHCs, not all of them have adequate facilities. From shortage of doctors to physical infrastructure and drugs, there are many bottlenecks to the effective functioning of PHCs in the country.

58% of PHCs in India are concentrated in six states with 54% Rural Population

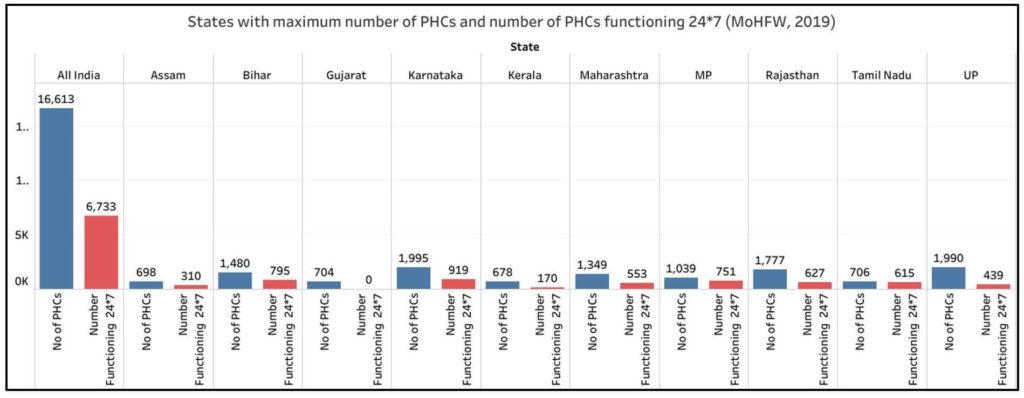

Data from the Ministry of Health shows that there is a total of 16,613 PHCs functioning in India as of 31 March 2019. Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan have more than 1700 PHCs each while Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra also have more than 1000 PHCs each. 58% of the PHCs in the country are concentrated in these six states. These 6 states account for 54% of the rural population of the country as per the 2011 Census. It must be noted that Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Goa have Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) in place of PHCs.

Not even half of the PHCs function round the clock

Only 40.5% of these PHCs (6,733) in the country are functional 24*7. Sikkim is the only state where all the 24 PHCs function round the clock. Among other states, only Tamil Nadu, Tripura, Manipur, Punjab, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Mizoram have more than 70% of the PHCs rendering 24*7 service. Despite home to a large number of PHCs, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan have only about 22% and 35% of the PHCs functioning 24*7 respectively. No PHCs function round the clock in Gujarat.

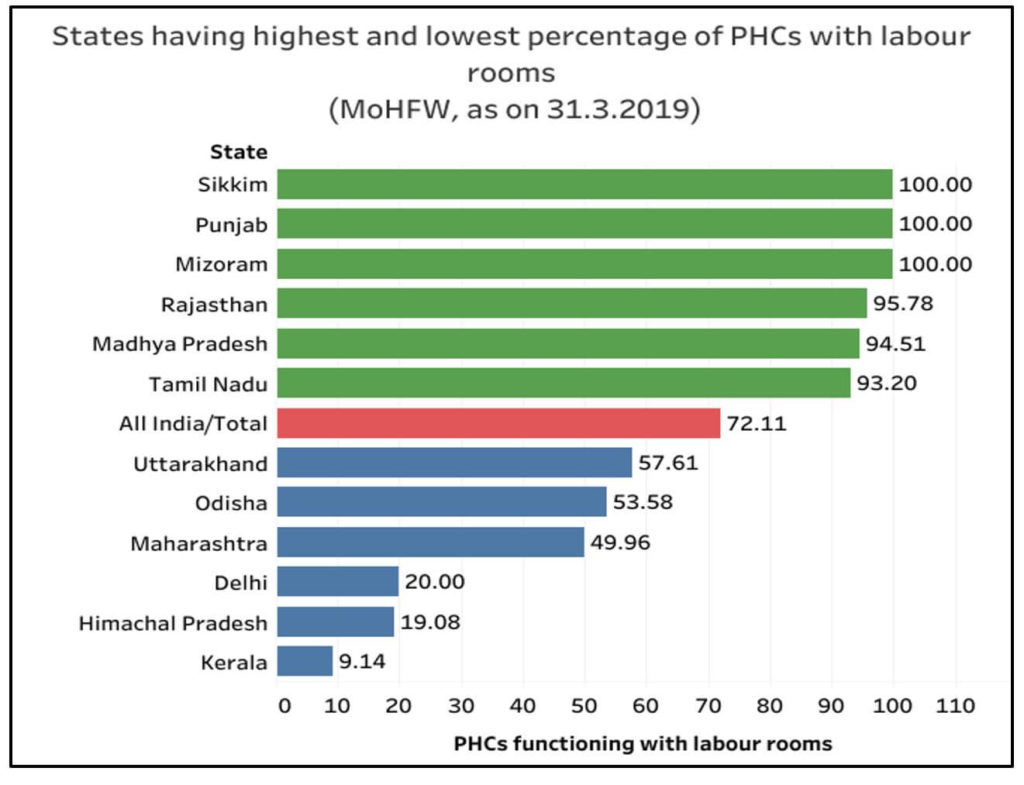

Labour rooms, though essential, are unavailable in 28% of the PHCs

Though labour rooms are considered essential in PHCs, data shows that only 72% of the PHCs in the country have labour rooms. The labour rooms are supposed to be equipped with basic medical equipment that are necessary for mothers & infants such as oxygen supply, suction machines etc. Less than 50% of PHCs in Maharashtra, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, and Kerala have labour rooms.

Meanwhile, operation theatres are optional in PHCs. However, only select surgical procedures can be carried out, such as vasectomy, tubectomy, and hydrocelectomy even if there is an operation theatre. There should be separate facilities for the storage of sterile and unsterile equipment, regular fumigation of the theatre, and a separate area for changing and sterilization. Across the country, around 36.5% of the PHCs have operation theatres. All the PHCs in the states of Punjab, Sikkim, and Mizoram have operation theatres.

Almost a quarter of PHCs in India do satisfy the minimum requirement of 4 beds

As per the guidelines of the Indian Public Health Standards, every PHC should have at least 4 to 6 beds, with earmarked wards for males and females. It also necessary that these wards have separate toilets for males and females. But less than 77% of the PHCs have the minimum requirement of 4 beds. Mizoram, Sikkim, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, and West Bengal are the states which have fulfilled the requirement in all the PHCs. Less than half the PHCs in Maharashtra, Himachal Pradesh, Assam, Kerala, Odisha, and Delhi have 4 beds.

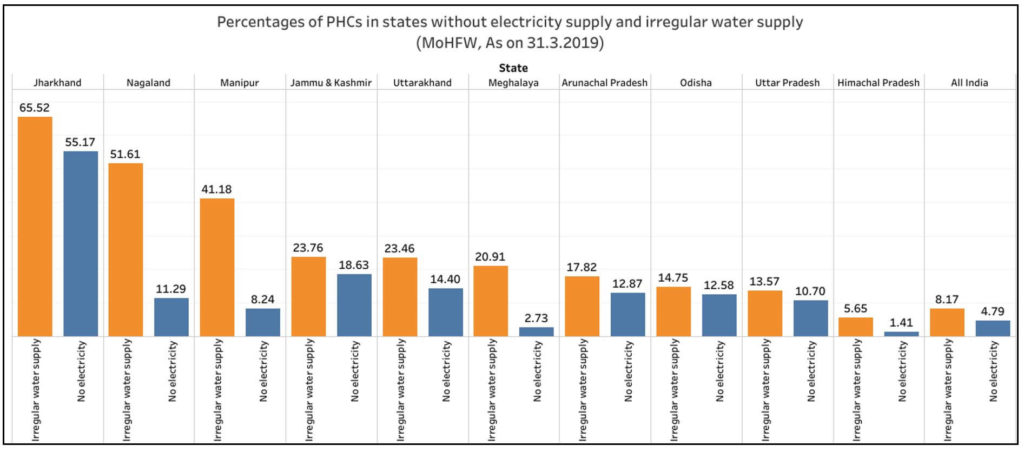

More than half the PHCs in Jharkhand do not have electricity and two-thirds do not have regular water supply

Electricity supply and regular water supply are two important basic amenities required for functioning of PHCs. Electricity supply is required for storage of vaccines, emergency services including deliveries and surgeries. It is alarming to note that about 4.8% of the PHCs (1590) in the country do not have electricity supply and 8.2% of them (2716) do not have regular water supply. In Jharkhand, even though the state has fared above national average in terms of PHCs functional 24*7 and availability of labour rooms, 55.2% of the PHCs do not have electricity supply and 65.5% of them do not have a regular water supply.

Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and Nagaland have also reported more than 10% of the PHCs functioning without electricity supply. In Nagaland, Manipur, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, and Meghalaya, at least 20% of the PHCs do not have regular water supply. States of Tamil Nadu, Sikkim, Punjab, Bihar, Kerala, and Delhi have electricity and water supply in all PHCs.

More than 15% of the PHCs in each of Arunachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Jammu and Kashmir, and Nagaland, do not have an all-weather motorable approach road. At the national level, there are around 1,355 PHCs without an all-weather motorable approach road. Though the availability of a computer with internet connectivity for data management is mandatory, only about 76.5% of PHCs in the country have a computer and 57% have a telephone.

Government has to strengthen the public healthcare in India

Public health and hospitals are state subjects. Recruitment of doctors, and other administrative matters in PHCs thus fall under the purview of respective state governments. Financial support and technical support are extended to states and UTs by the centre through National Health Mission. As is evident from the data, PHCs in India do not even have the minimum required infrastructure as mandated by the relevant guidelines. The status of public healthcare system in the country will not improve unless governments invest more in these facilities. Lack of such facilities in the public sector forces people to approach private hospitals resulting in increased out of pocket expenditure. Lack of these basic facilities also discourage doctors from working in PHCs which predominantly cater to the needs of the rural poor. In addition to poor infrastructure, skewed distribution of doctors and paramedical staff and their shortage is another important issue that is plaguing the public health system. COVID-19 has once again reminded us of the importance of strengthening our public health systems right from the grass roots.

Featured Image: Infrastructure of Primary Health Centers