In this week’s review of court judgments, we look at the Supreme Court’s judgements about delays in criminal complaints, conviction of public servant under Prevention of Corruption Act, observations on scope of delegated legislation, Madras High Court’s judgement granting bail to accused in Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002, and Kerala High Court’s judgement on dowry under the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961.

Supreme Court: Unexplained inordinate delay of such length must be taken into consideration as a very crucial factor as grounds for quashing a criminal complaint

In Hasmukhlal D. Vora & Anr. vs. The State of Tamil Nadu, the apex court held that though inordinate delays by themselves may not be a ground for quashing criminal complaints, unexplained inordinate delays must be considered as crucial factor as grounds for quashing a criminal complaint.

A two-judge bench comprising of Justice Krishna Murari and Justice S. Ravindra Bhat, was hearing an appeal against the order of the Madras High Court, where the petitioner’s plea under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 to quash the criminal complaint was dismissed.

The appellants run a company under name M/s. Chem Pharm, a trader of raw material chemicals used in food, food supplements, medicinal preparations. They had purchased 75 Kg of pyridoxal-5-phosphate in 3 packets of 25 kg each. On a surprise inspection by the Drug Inspector, it was alleged that the Appellants sold the bulk amount of pyridoxal-5-phosphate in violation of Rule 65(5)(1)(b) of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules 1945 and Section 18(c) of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940. A show cause notice was issued after three years to which the appellants responded. Citing the lapse, the appellants filed a complaint for quashing the complaint, which the Madras High Court dismissed. It held that,

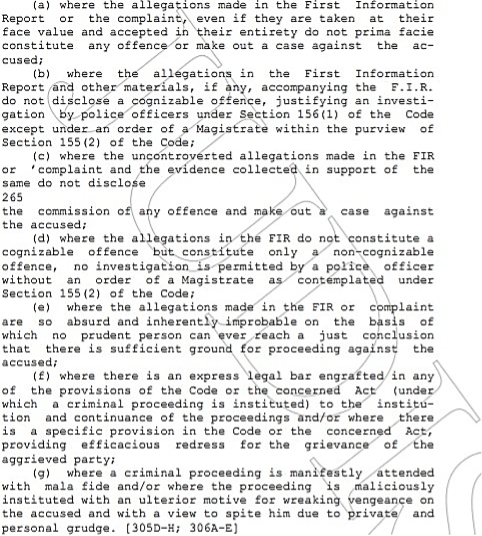

The apex court heard the arguments of counsels from both the sides. It referred to State of Haryana & Ors. vs. Bhajan Lal & Ors, where it laid down the guidelines for quashing criminal complaint.

It further referred to the R.P. Kapur vs. State of Punjab, whereby it was held that a court may use its authority to dismiss a criminal complaint if there is no lawful evidence or if the evidence is blatantly incongruous with the charges. Further, in Bijoy Singh & Anr. vs. State of Bihar, the court held that excessive delay, if not well justified, can be fatal to the prosecution’s case. In fact, the Court is only led to believe that there was a malicious reason for starting the criminal proceedings by the lack of such an explanation.

Further, the court reiterated that the purpose of starting criminal proceedings must be to uphold the interests of justice, and that the accused cannot be made the target of legal harassment. Accordingly, the apex court held that the High Court failed to look into the facts and circumstances of the case and set aside the High Court order.

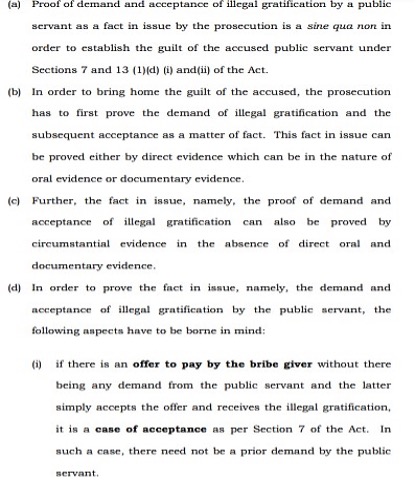

Supreme Court: In the absence of evidence of the complainant, it is permissible to draw an inferential deduction of culpability/guilt of a public servant under Section 7 and Section 13 of the Prevention of Corruption Act

In a major ruling, the five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that direct evidence of demand of bribe is not necessary to convict a public servant under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 in Neeraj Datta vs. State ( Govt. of NCT of Delhi).The case was referred to a five-judge bench by a three-judge bench considering the validity of the position of the law.

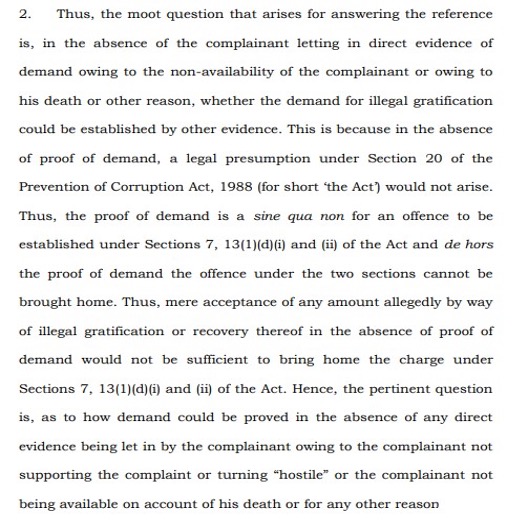

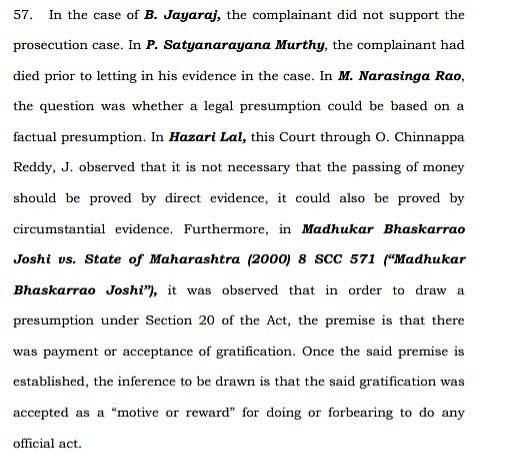

The case relates to the conflict in the interpretation and judgements regarding the nature and quality of proof necessary to sustain a conviction for the offences under Section 7 and 13(1)(d) read with Section 13(2) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 when the primary evidence of the complainant is unavailable. Judgements in B. Jayaraj vs. State of Andhra Pradesh , andP. Satyanarayana Murthy vs. District Inspector of Police, State of Andhra Pradesh, and Another, are in conflict with the judgement in M. Narsinga Rao vs. State of A.P. The conflict is as below.

The court heard the arguments of the counsels regarding the issues in the quality and nature of the proof in corruption cases against the public servant.

Upon hearing the counsels and the precedents in other judgements, the apex court concluded that with reference to the type and standard of proof required to uphold a conviction for offences under Sections 7 or 13(1)(d)(i) and (ii) of the Act, when the complainant’s direct evidence, or “primary evidence,” is unavailable, there is no conflict between the three judge bench decisions of the Court in B. Jayaraj and P. Satyanarayana Murthy and the three judge bench decision in M. Narasinga Rao. In light of Section 154 of the Evidence Act, the legal position in cases where a complainant or prosecution witness becomes “hostile” is also considered.

Therefore, in the absence of evidence of the complainant (direct/primary, oral/documentary evidence) it is permissible to draw an inferential deduction of culpability/guilt of a public servant under Section 7 and Section 13(1)(d) read with Section 13(2) of the Act based on other evidence adduced by the prosecution.

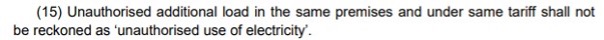

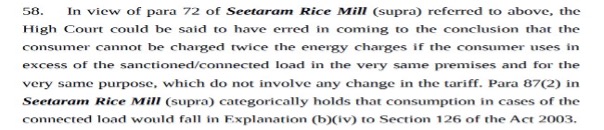

Supreme Court: Electricity consumption beyond the limit of connected or contracted load amounts to ‘unauthorised use of electricity’

The apex court, in Kerala State Electricity Board vs. Thomas Joseph Alias Thomas M J held that according to Section 126(6)(b) of the Electricity Act of 2003, “unauthorised use of electricity” is defined as consumption of electricity in excess of the connected load or contracted load, and the excessive overdraw of electricity harms the general public because it could disrupt the entire supply system, reducing its effectiveness and efficiency and leading to even greater voltage fluctuations.

The apex court was hearing an appeal against the judgement of Kerala High Court, which had held that even in cases where users are paid based on the connected load, “unauthorised additional load” in the same location and under the same tariff shall not be considered “unauthorised usage of electricity” relying upon the Section 154 (15) of the Kerala Electricity Supply Code, 2014.

Section 126(6) of the Electricity Act, 2003 defines unauthorized use of electricity as below.

The counsels for the appellants argued that by relying on Regulation 153(15) of the Code 2014 to decide the matter in question, the High Court made a grave error. They emphasised that the State Regulations were created using the authority granted by Section 50 read in conjunction with Section 181 of the Act 2003. The Counsel also argued that the ability to make regulations could not be used to create substantive rights that were not included in the Act of 2003. The Counsel further pointed out that Section 126 of the Act of 2003 is a full code in and of itself as held by this Court The Executive Engineer & Anr vs. M/s Sri Sitaram Rice Mill case.

Having heard the arguments of both counsels, the apex court held that Section 126 of the Electricity Act, 2003 is self-explanatory, and while dealing with situations other than section 135 of the act, the courts must interpret in a way that the legislative intent is satisfied. It held that High Court had erred in adopting a narrower conclusion in a situation where the public at large might be affected.

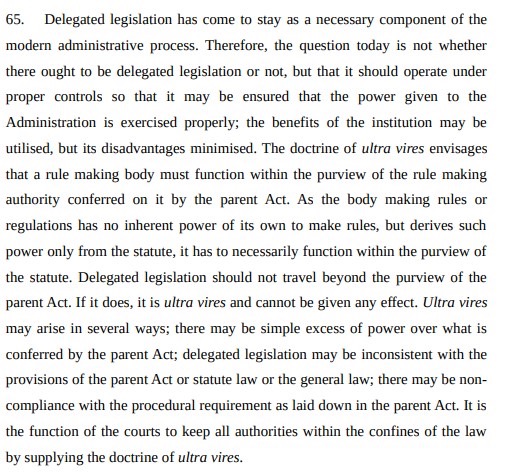

Further, the court provided insights on the delegated legislation and its extent. It held that ‘A delegated power to legislate by making rules or regulations ‘for carrying out the purpose of the Act’, is a general delegation without laying down any guidelines; it cannot be exercised to bring into existence the substantive rights or obligations or disabilities not contemplated by the provisions of the Act 2003 itself’. It further held that when determining whether a subordinate statute is valid, the Court will have to consider the nature, purpose, and plan of the enabling Act as well as the territory over which authority has been granted by the Act. Any rules or regulation cannot be made to supplant the provisions of the parent act but only to supplement it.

Madras HC: Right of personal liberty and individual freedom cannot arbitrarily be taken away from anybody even temporarily without following the procedure prescribed by law

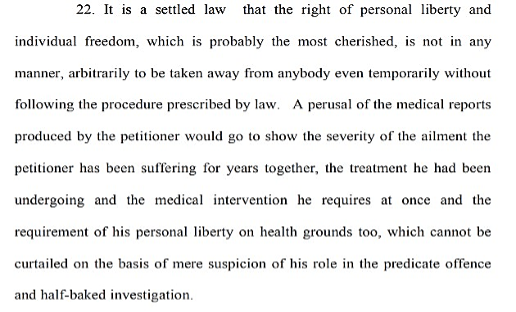

In Narendra Kumar Gupta vs. State rep by Assistant Director, Directorate of Enforcement, the Madras High Court held that right to personal liberty and individual freedom, which are the most cherished, cannot be arbitrarily taken away from anyone, and any curtailment just on the basis of mere suspicion and half-baked investigation is not justified.

A single judge bench of Justice A.D. Jagadish Chandira was hearing a bail petition filed by the accused under Section 3 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002. The counsel for the petitioner argued that the petitioner is unaware of the purported payments from Indian traders Star Overseas and Bhagya Lakshmi Traders that the Company is said to have received in Hong Kong. By pretending to receive financial assistance from Hong Kong and taking advantage of the petitioner’s financial problems, Sukhjeet Singh improperly utilised the petitioner’s name to handle these transactions. The petitioner is unaware of the origin of these funds and does not know how they have been used in Hong Kong. The counsel further argued that

The counsel also pointed out the bad health of the petitioner suffering from serious heart ailments and is ready to produce sureties and abide by any conditions of bail and hinted at the grant of bail to two other similarly placed persons by the court.

The Enforcement Directorate argued that the petitioner could not claim ignorance of the repercussions of his own acts in signing the paper and that he was accountable for the company’s operations under Section 70 of PMLA. Additionally, it was argued that bail could not be given for serious offences when there was adequate medical care available inside the prison itself. Additionally, it was stated that because the function of the accused in money laundering instances varies from person to person, bail amounts granted to others in comparable situations did not apply to the current case.

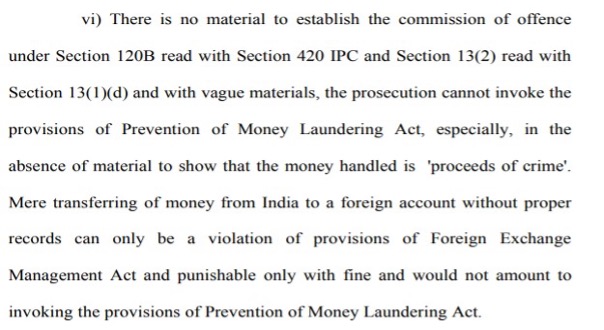

Considering the arguments from both sides, the Madras High Court agreed with the arguments of the petitioner’s counsel and held that a simple reading of Section 2(1)(u) of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 would make it evident that there cannot be any money laundering without any proceeds of crime. If at all, receiving money or having money from abroad would be subject to the Foreign Exchange Management Act of 1999 and not the Prevention of Money Laundering Act of 2002. It further held that,

Accordingly, the bail is granted to the petitioner on certain conditions.

Kerala HC: Dowry demanded at or before, or any time after the marriage in connection with the marriage attracts the provisions of Dowry Prohibition Act

The Kerala High Court held that provisions of Dowry Prohibition Act,1961 apply even in cases where there is a subsequent demand for dowry after marriage, in Kiran Kumar S vs. State of Kerala & Anr case.

The High Court was hearing an application seeking the suspension of 10-year sentence and grant of bail, filed by the convict in the vismaya dowry death case. The petitioner was convicted and sentenced under Sections 304B, 306 and 498A of the Indian Penal Code and Sections 3 and 4 of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. The counsel for the petitioner argued that court findings was based on contents of call records, which were never investigated. Further, there is no conclusive material evidence to show that she was subjected to matrimonial cruelties, physical or mental or abetted her suicide.

The Special Government Pleader argued that no exceptional circumstances are brought out to suspend the sentence and to release him on bail. Since there is finding of competent court of jurisdiction, on the guilt of the applicant/accused, he cannot claim the benefit of presumption of innocence, for the purpose of getting suspension of sentence awarded by the trial court.

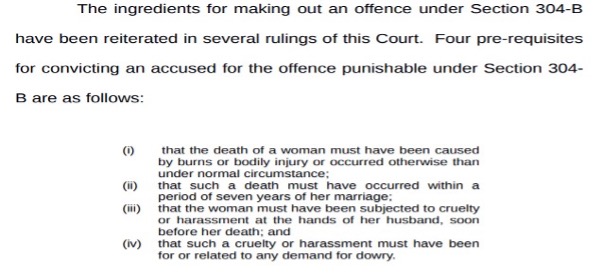

The Court heard the arguments from both sides and relied on the judgement in State of Madhya Pradesh vs. Jogendra and Another for analysing the provisions of Section 304B of IPC.

Further, the apex court also held that, ‘The phrase “soon before” as appearing in Section 304-B IPC cannot be construed to mean “immediately before”. The prosecution must establish existence of “proximate and live link” between the dowry death and cruelty or harassment for dowry demand by the husband or his relatives’, and any interpretation of the Section 304B by the courts must be done keeping in mind the legislative intent to curb the social evil of dowry demand.

The Kerala High Court further relied on the judgement of apex court in Preet Pal Singh vs. State of Uttar Pradesh and Another, regarding the suspension of sentence, where it held that discretion is to be exercised judicially and not in a casual manner, while suspending the sentence and releasing the convict on bail, pending appeal. This exercise of jurisdiction has to be based on well-settled principles of law and in a judicious manner.

Further, Kerala High Court held that if the sentence is suspended, it will send a wrong message to the society, and therefore dismissed the petition.