In this edition of the court judgements review, we look at the Supreme Court’s judgements on the rights of the voter, conditions for bail, suspending of a doctor’s license as a penalty, the Kerala High Court’s judgement on section 13(1)(c) of Prevention of Corruption Act, Calcutta High Court’s decision on the time limit for POCSO FIRs, and Patna High Court’s order on grounds for dissolution of marriage.

Supreme Court: The right to vote, based on an informed choice, is a crucial component of the essence of democracy, voter has the right to know full background of the candidate.

In Bhim Rao Baswanth Rao Patil vs. K. Madan Mohan Rao & Ors., the Supreme Court held that the voter has a right to know the complete background of the candidate, as the casting of a vote in favour of one or other marks the accomplishment of freedom of expression of the voter.

A two-judge bench of the apex court, comprising of Justice S Ravindra Bhat and Justice Aravind Kumar was hearing an appeal against the order of the Telangana High Court that dismissed the petition seeking rejection of the election petition filed against Bhim Rao Baswanth Rao Patil (appellant). He was elected to the Zaheerabad Parliamentary constituency in 2019. However, as claimed by the respondent, the appellant had filed false information in Form 26, and the Returning Officer did not follow the guidelines of the Election Commission regarding the pending cases against the appellant. Hence, the election petition was filed before the High Court under Sections 81 and 84 read with Sections 100(1)(d)(i)(ii)(iii) & (iv) of the Representation of People Act,1951. The appellant under Order VII Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure (hereafter “CPC”) argued for its rejection.

While the counsel for the appellant argued that accepting the petition amounts to an abuse of process and a clear case of interpolation, the counsel for the respondent argued that Courts are duty-bound to examine the allegations whenever the same is raised within the framework of the statute without being unduly hyper-technical in their approach and oblivious of the ground realities.

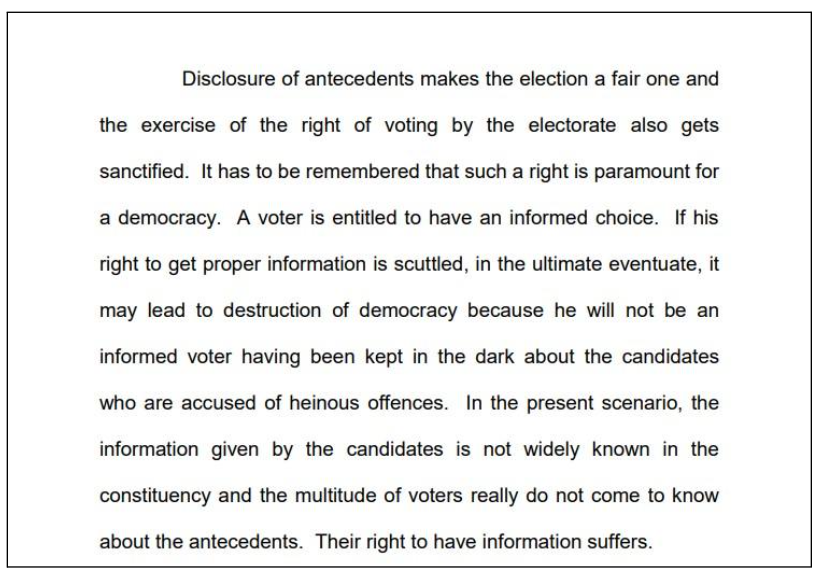

The apex court looked at Section 33A of the RPA,1951 which was introduced to compel those holding out their candidature to disclose information about their criminal antecedents. The apex court judgement in the Public Interest Foundation & Ors vs. Union of India & Ors. also highlighted the need for a detailed declaration by the candidates.

The apex court also held the provision 33B of the RPA 1951 that provided that no candidate shall be liable to disclose or furnish any such information, in respect of his election, which is not required to be disclosed or furnished under this Act or the Rules made thereunder as invalid in People’s Union for Civil Liberties vs. Union of India.

Further, the appellant did not deny the allegations of non-disclosure of pending cases but rather argues that no such disclosure of this kind is needed since they did not fall under the section 33A of the RPA 1951. The apex court held that the right to vote, based on an informed choice, is a crucial component of the essence of democracy. This right is precious and was the result of a long and arduous fight for freedom. The elector or voter’s right to know about the full background of a candidate evolved through court decisions- is an added dimension to the rich tapestry of our constitutional jurisprudence.

Further, the apex court held that if the withholding of information is seen as insignificant, the court would be pre-judging the issue without the completion of the trial. Accordingly, the apex court agreed with the decision of the High Court in not rejecting the election petition. The current appeal was dismissed.

Supreme Court: Conditions for grant of bail must consider the socio-economic realities of the accused.

The Apex Court, while hearing a Suo Moto writ petition on the issuance of a comprehensive policy strategy for the grant of bail, held that the bail conditions must be realistic of the socio-economic background of the accused.

The division bench of the apex court comprising of Justice S K Kaul and Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia was hearing the Suo moto petition on bail conditions. They were assisted by Amicus Curiae, Advocate Gaurav Agarwal. The Amicus Curiae informed the bench that 5380 undertrial prisoners were identified as persons who were granted bail but were not released for several reasons as per the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA).

The issue of clogged prisons was earlier highlighted during the previous hearings of this case. The then bench suggested an out-of-box thinking to unclog the prisons. During the same hearing, the apex court directed the National Informatics Centre (NIC) to modify the e-prison software by adding an entry for the date of grant of bail, and if the accused is not released within seven days from such date, it would send an automated email to the concerned District Legal Services Authority (DLSA).

Adding to this, in the present hearing, the apex court held that the bail conditions must be in such a way that they should be fruitfully met. Consideration must be given to the social and economic conditions of the accused. Otherwise, the act of grant of bail would not subserve the purpose. The matter is further listed for future hearings.

Supreme Court: Doctor’s License cannot be suspended as penalty under Contempt of Courts Act 1971.

In Gostho Behari Das vs. Dipak Kumar Sanyal & Ors, the apex court held that a doctor’s license cannot be suspended as a punishment in contempt proceedings. The division bench of the apex court comprising of Justice BR Gavai and Justice Sanjay Karol was hearing an appeal against the order of the Calcutta High Court that upheld the judgement of a single judge bench which suspended the doctor’s license of the appellant as penalty in contempt proceedings.

The issue before the court was, “Whether the suspension of the Petitioner’s license to practice medicine is alien to the nature and types of punishment and penalties specified under the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971?”.

The brief facts of the case are as follows. The appellant had unauthorizedly constructed a structure that was not according to the plans submitted to the Siliguri Municipal Corporation (SMC). In subsequent cases at various forums against the illegal structure, it was decided that the appellant shall make self-demolition, failing which the SMC should take necessary measures to demolish. When the appellant did not self-demolish the structure, a contempt petition was filed, under which the doctor’s license was suspended.

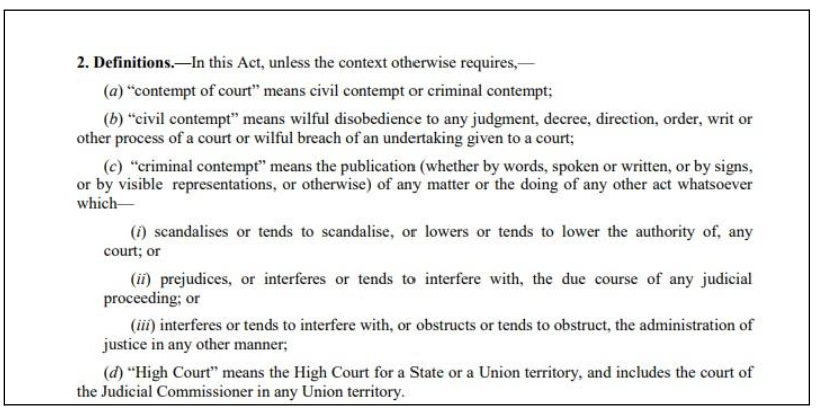

The apex court observed that the grant, regulation and suspension of the license to practice medicine is governed by the National Medical Commission Act, 2019. The current dispute is whether such action can be taken under the Contempt of Courts Act, of 1971. ‘Contempt’ is defined under this act as.

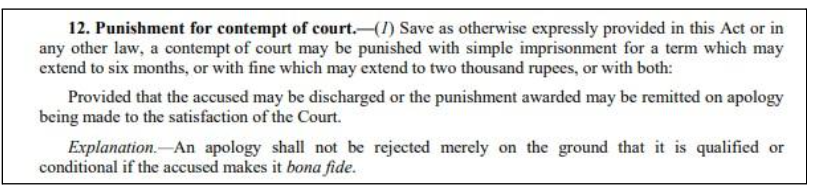

The punishment for contempt is defined under section 12 as follows:

The court relied on the judgement in C.S. Karnan, wherein it was held that the justification for the existence of such power is not for the protection of the judges, but to inspire confidence in the sanctity and efficacy of the judiciary. The object of the discipline enforced by the Court in case of contempt of court is not to vindicate the dignity of the court or the person of the Judge but to prevent undue interference with the administration of justice.

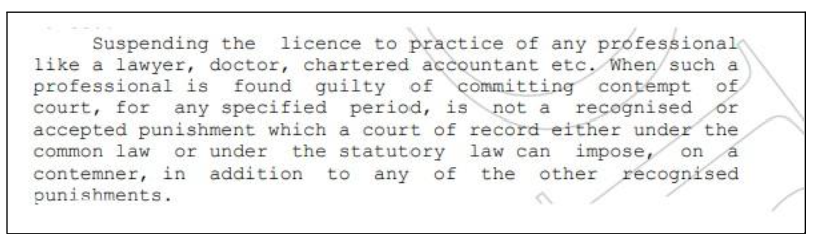

Further, the apex court in Supreme Court Bar Association vs. Union of India, held that,

Further, the court highlighted the necessity to look at the nature and gravity of the contemptuous conduct before deciding on the penalty.

Accordingly, the apex court found the judgement of the High Court unsustainable, and the license of the appellant, to practice medicine is revived.

Kerala HC: ‘Misappropriation’ and ‘Criminal Breach of trust’ are essential ingredients for establishing the offence under section 13(1)(c) of the Prevention of Corruption Act,1988.

The Kerala High Court, in Enose vs. State of Kerala, held that the prosecution must prove the ingredients of misappropriation and criminal breach of trust to attract the provisions of section 13(1)(c ) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (PC Act).

The Single judge bench comprising of Justice Kauser Edappagath was hearing an appeal against the judgement of the Enquiry Commissioner and Special Judge, Thiruvananthapuram, that convicted and sentenced the appellant under Sections 13(2) r/w 13(1)(c) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. The brief facts of the case are as follows.

The appellant was employed on deputation as an L.D. Clerk by the Directorate of Higher Secondary Education in Thiruvananthapuram. The disbursement, withdrawal, and deposit of money into the Treasury are all part of his job duties. The Directorate of Higher Secondary Education was granted Rs. 5,90,000 for its examination division. The accused employee’s A-Section withdrew the aforementioned sum and turned it over to D-Section. On 10 March 1998, the D-Section handed over the accused and returned to the A-Section the unused fraction of the sum of Rs. 74,789. According to the prosecution, the accused misappropriated the said sum and kept it on his person until 02 April 2022, by entering false information in the Cash Book to make it look as though the stated sum had been transferred.

The High Court observed that the prosecution must establish that the accused was given property to be used in trust and then dishonestly took it for his own use to commit the crime of criminal breach of trust. Further, to prove an offence under section 13(1)(c) of the PC Act, the prosecution must also demonstrate the same elements of criminal breach of trust and misappropriation. It relied on the apex court’s judgement in Jaikrishnadas Manohardas Desai and Another vs. State of Bombay

The Kerala High Court agreed with the findings of the special judge and did not find a reason to interfere with the findings. Accordingly, the appeal is dismissed.

Calcutta HC: A delay in filing FIR by the victim in cases of sexual assault should not be a cogent reason for quashing the investigation against the accused.

The Calcutta High Court, in Shreekant Sharma vs. The State of West Bengal & Anr, held that delay in filing FIR in cases of sexual assault, should not be equated with other cases to quash proceedings or hold an accused not guilty. Further, a victim refusing to give her consent for medical examination cannot be a reason to quash the FIR if the results are not of material importance to the case.

The single-judge bench headed by Justice Bibek Chaudhuri was hearing a petition for quashing criminal proceedings under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO Act), 2012. The grounds for quashing as raised by the petitioners are delay in filing the FIR, and refusal to give consent for medical examination. It was further contended that there are admitted differences between the parents and the current FIR is filed with a malaise intention.

The court looked at the facts and material records of the case. The Calcutta High Court relied on the judgement of the apex court in Satpal Singh vs. State of Haryana, wherein it was observed that in rape cases, the family of the victim shows reluctance to reach the police, particularly due to the social stigma. Further, delay in lodging FIR more often than not, results in embellishment and exaggeration, which is a creature of an afterthought. Thus, if there is any delay in filing FIR, the prosecution must furnish a satisfactory explanation for the same reason.

In State of Himachal Pradesh vs. Prem Singh, the apex court highlighted the need to not equate cases of sexual assault with other cases. Relying on the judgements, the court did not agree with the contentions of the petitioners and believes that there was a sufficient reason which explained the cause of delay in filing the FIR.

On the refusal to undergo medical examination as being violative of Section164A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 along with Section 27 of the POCSO Act,2012 , the court held that medical examination of the victim would not have yielded such results which could have proved to be of material importance for the conviction of the victim as this case was not of penetrative act. The court believes that it cannot quash the investigation at this stage of the trial for technical matters.

On quashing the FIR, the court relied on State of Haryana vs. Bhajan Lal, which looked at the power of the High Court to quash criminal proceedings or FIR. The court finds that the facts of the case did not fall under any exceptions quoted in the judgement. Accordingly, the petition is dismissed.

Patna HC: Inability to bear a child may be part of marital life of anybody, not a ground for dissolving the marriage.

In Sonu Kumar vs. Rina Devi, the Patna High Court held that the inability to bear a child is neither impotence nor any ground for dissolving the marriage. The parties to a marriage may resort to other means for having a child, such as adoption.

The two-judge bench comprising of Justice P.B. Bajanthri and Justice Jitendra Kumar was hearing a revision plea against the order of the Family court that dismissed the appellant matrimonial case for divorce. The appellant contended that the wife did not conduct properly with the parents of the appellants and refused to come back to his matrimonial home. Further, when she underwent several tests for ill-health, it was found that she had a cyst in the uterus, and she has the least possibility of becoming a mother. On the other hand, the appellant is a young man of 24 years of age having good health needing cohabitation and having desire to become a father, but the respondent-wife is neither willing to cohabit nor is any possibility of her becoming a mother. Hence the plea for divorce.

Upon hearing both sides, the Patna High Court held that the appellant failed to provide any evidence to his allegations, with reference to the date, place and nature of the cruelty except the general allegation that she refused to cohabit with him. The court also found that the husband did not take any legal step for restitution of conjugal rights by filing a petition under Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 indicating that the claim of refusal to cohabit lacked grounds.

The court highlighted that developing any disease during the continuation of marriage is not within the control of any spouse. Further, it is the marital responsibility of the spouse to help each other.

Accordingly, the court found no merit in the present appeal warranting any interference in the impugned judgment. The present appeal is dismissed.