In this edition of court judgements review, we look at the Supreme Court’s judgements on enforceability of arbitration agreements, issue of ‘equal pay’ for allopathy and ayurvedic doctors, grounds for dissolution of marriage, Delhi High Court’s decision on Right to Publicity and Karnataka High Court’s decision on termination of workman.

Supreme Court: Arbitration agreement in a contract, which is not registered and stamped, but is required to be registered and stamped is not enforceable.

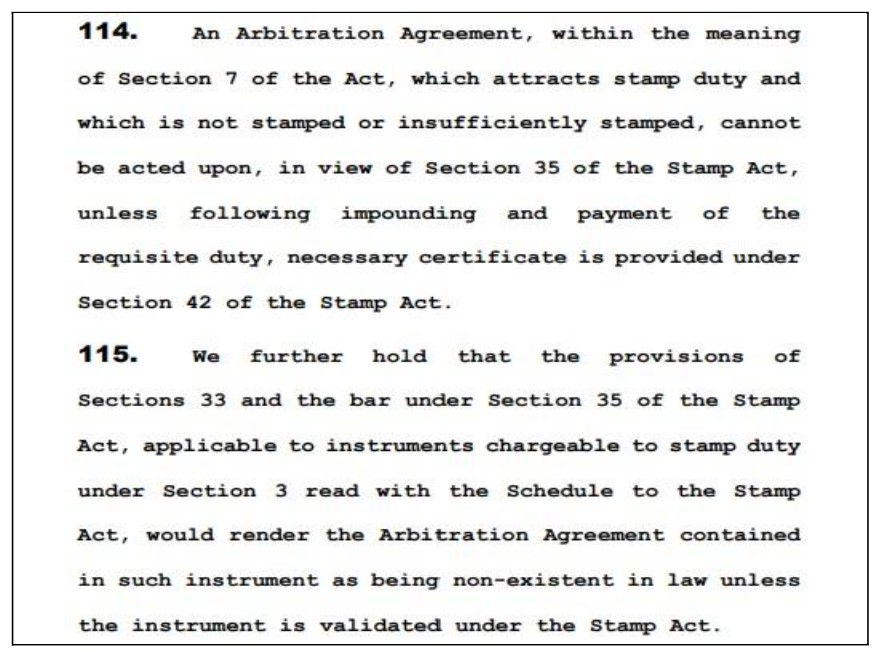

In M/s. N.N. Global Mercantile Pvt. Ltd. vs. M/s. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. And Ors, (N.N. Global) the Supreme Court, in a 3:2 majority, held that an instrument, which is exigible to stamp duty, may contain an Arbitration Clause and which is not stamped, cannot be said to be a contract, which is enforceable in law within the meaning of Section 2(h) of The Indian Contract Act, 1872 (hereby referred to as ‘Contract Act’) and is not enforceable under Section 2(g) of the Contract Act.

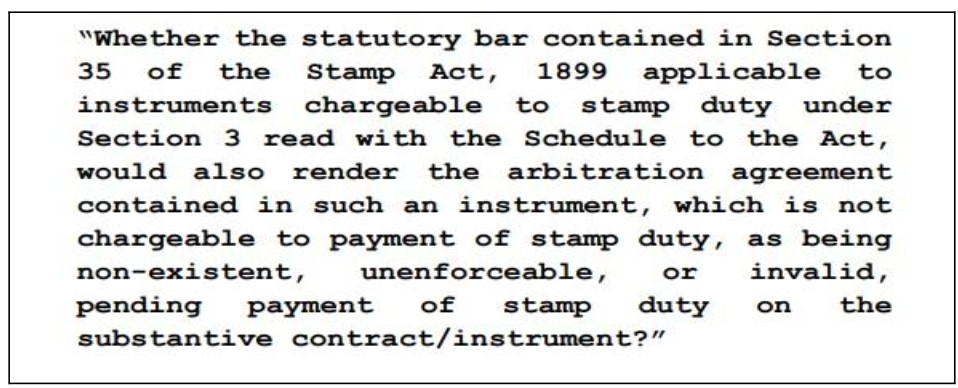

The five-judge Constitution Bench headed by Justice KM Joseph was hearing the issue of enforceability of contract in the absence of stamp and registration, referred by the three-judge bench of the apex court. The three-judged bench in this case held that, the views in SMS Tea Estates Pvt. Ltd vs. M/s. Chandmani Tea Co Pvt. Ltd (SMS Tea Estates) and Garware Wall Ropes Limited vs. Coastal Marine Constructions and Engineering Limited (Garware) is not the correct position of law, and when these views were reaffirmed by a coordinate Bench in Vidya Drolia vs. Durga Trading Corporation (Vidya Drolia), the aforesaid issue is required to be authoritatively settled by a Constitution Bench of this Court. The issue is as below.

After analysing the case history and evolution of legal jurisprudence through various judgements over the years, the majority view, consisting of Justice KM Joseph, Justice Aniruddha Bose, and Justice CT Ravikumar, held that the position taken by the apex court in SMS Tea Estates and Garware, as to the effect of an unstamped contract containing an Arbitration Agreement and the steps to be taken by the Court, represent the correct position in law. This was wrongly decided in the present case, N.N. Global by the three-judge bench. The apex court referred to The Indian Contract Act, 1872, The Indian Stamp Act 1899, and The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

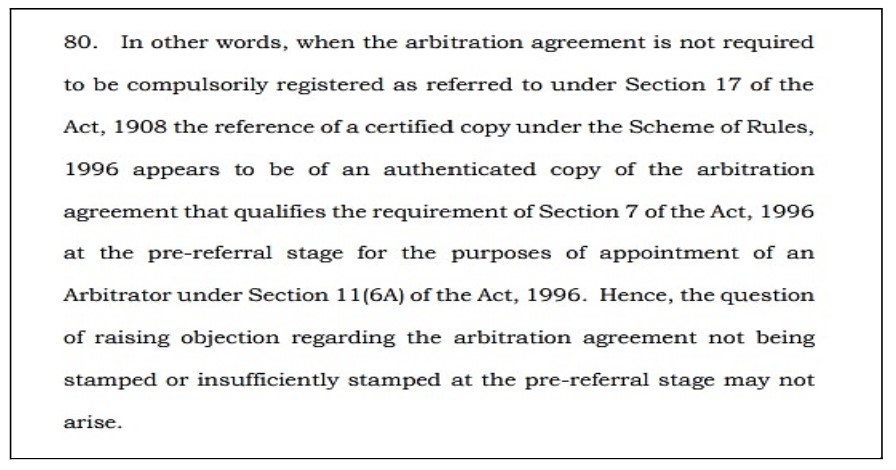

The minority view by Justice Ajay Rastogi, and Justice Hrishikesh Roy, held that at the pre-referral stage, as described in Section 11, the examination of stamping and impounding inspection may not be done. Also, the copy or certified copy of the arbitration agreement—regardless of whether it is unstamped or insufficiently stamped—is an enforceable document for the appointment of the arbitrator at the pre-reference stage.

Supreme Court: Cannot be oblivious to the fact that Ayurveda and Allopathy doctors perform different duties, hence not entitled to equal pay.

The apex court, in the State of Gujarat And Ors. Etc. vs. Dr. P.A. Bhatt And Ors, held that allopathy and ayurvedic doctors do not perform equal work and therefore are not entitled to the same pay and benefits. The court was referring to appeals arising out of the judgement by the division bench of the Gujarat High Court holding that ayurvedic and allopathic doctors are entitled to the same benefits recommended by the Tikku Pay Commission.

The factual background of the case is as follows. On 03 May 1990, a High-Power Committee was established with R.K. Tikku as its chairman with the goal of enhancing the opportunities and working circumstances for doctors employed by the government. The committee’s recommendations were only for service doctors with MBBS degrees, post-graduate medical degrees, degrees in super-specialties, and those on the teaching and non-teaching sides when they were submitted in October 1990. By a different order, a new committee was established with the same chairman to consider the career advancement and cadre reorganisation of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homoeopathy practitioners. The committee’s report was submitted in February 1991.

The Governments at both state and central levels accepted the recommendations of the Tikku Committee regarding allopathic doctors. However, when clarification was sought on whether the same benefits are available to non-MBBS degree holders, the Gujarat government responded in the affirmative. This was later withdrawn by a notification. The Division bench of the High Court held that no discrimination is permitted as both MBBS and non-MBBS degree holders form part of the same cadre, and both are entitled to equal pay and benefits. The appeal is against this order.

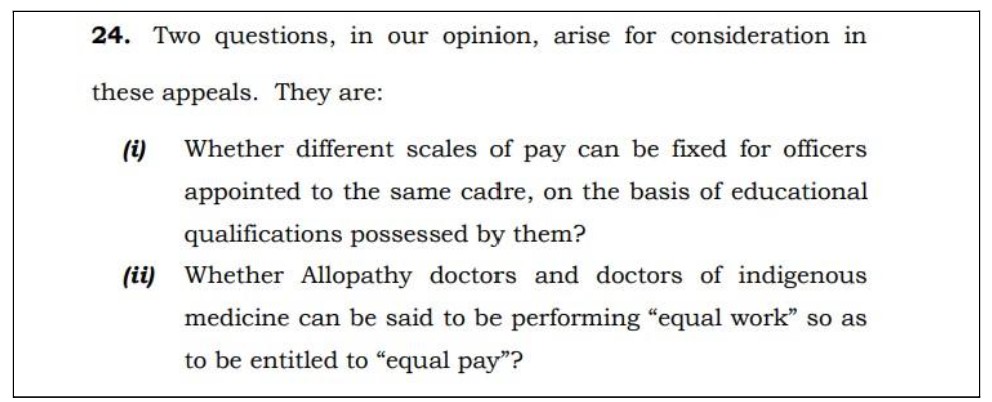

The Apex Court, comprising Justice V. Ramasubramanian and Justice Pankaj Mithal, analysed the submissions made by the parties and framed the issues for the consideration of the court.

On the issue of classification based on educational qualifications, the apex court held that it is not violative of Articles 14 and 16 of the Indian Constitution. The apex court relied on the judgement of the constitution bench in The State of Mysore vs. P. Narasinga Rao that upheld such classification. Further, it relied on Dr. C. Girijambal vs. Government of Andhra Pradesh, whereby it was held that,

Further, in Mewa Ram Kanojia vs. All India Institute of Medical Sciences, the apex court opined that ‘The doctrine of ’Equal Pay for Equal Work’ is not an abstract one, it is open to the State to prescribe different scales of pay for different posts having regard to educational qualifications, duties, and responsibilities of the post.’

Accordingly, on the first issue of whether a classification based on educational qualifications is valid, the apex court responded in the affirmative.

Regarding the second issue of equal work and equal pay, the apex court relied on the affidavit filed by the State government on the comparison of work between allopathy and ayurvedic doctors. The court held that ayurvedic doctors do not perform emergency duties as opposed to allopathic doctors. Further, MBBS doctors attend hundreds of outpatients in a day, which is not the case with ayurvedic doctors.

It held that both categories of doctors perform different duties and hence are not entitled to equal pay. Accordingly, the decision of the division bench of the High Court is set aside.

Supreme Court: Parties should not be permitted to file a writ petition under Article 32 of the Constitution of India, or for that matter under Article 226 of the Constitution of India before the High Court and seek divorce on the ground of irretrievable breakdown of marriage.

In Shilpa Sailesh vs. Varun Sreenivasan, the apex court, while upholding the powers under Article 142 of the Constitution to grant a divorce on grounds of irretrievable breakdown of marriage, held that parties shall not directly file writ petitions under Articles 32 and 226 of the Indian Constitution and seek relief under the above grounds.

The five-judge Constitution bench was hearing transfer petitions seeking clarifications on the questions of law, which are detailed below.

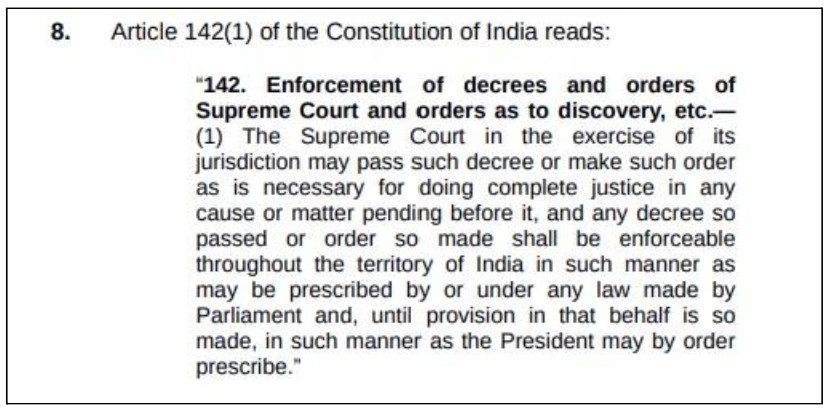

- The scope and ambit of power and jurisdiction of this Court under Article 142(1) of the Constitution of India.

- Whether the Supreme Court, while hearing a transfer petition, or in any other proceedings, can exercise power under Article 142(1) of the Constitution of India, in view of the settlement between the parties, and grant a decree of divorce by mutual consent dispensing with the period and the procedure prescribed under Section 13-B of the Hindu Marriage Act, and also quash and dispose of other/connected proceedings under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, or criminal prosecution primarily under Section 498-A and other provisions of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. What is the extent and scope of such power?

- Whether the Supreme Court can grant a divorce in the exercise of power under Article 142(1) of the Constitution of India when there is a complete and irretrievable breakdown of marriage despite the other spouse opposing the prayer.

On the question of scope and extent of Article 142:

The court held that, given the broad scope of authority granted by Article 142(1) of the Indian Constitution, the use of that authority must be lawful. It also begs for caution because using an individualistic approach to the use of constitutional authority can be dangerous. Since it has been ruled that relief based on equity should not disregard the substantive mandate of law based on underlying fundamental general and specific issues of public policy, this power, like all powers under the Constitution, must be contained and regulated. The power specifically bestowed by the Constitution on the apex court of the country is with a purpose and should be considered as integral to the decision in a ‘cause or matter’. As long as ‘complete justice’ required by the ‘cause or matter’ is achieved without violating fundamental principles of general or specific public policy, the exercise of the power and discretion under Article 142(1) is valid and as per the Constitution of India.

On divorce under Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 and the period prescribed.

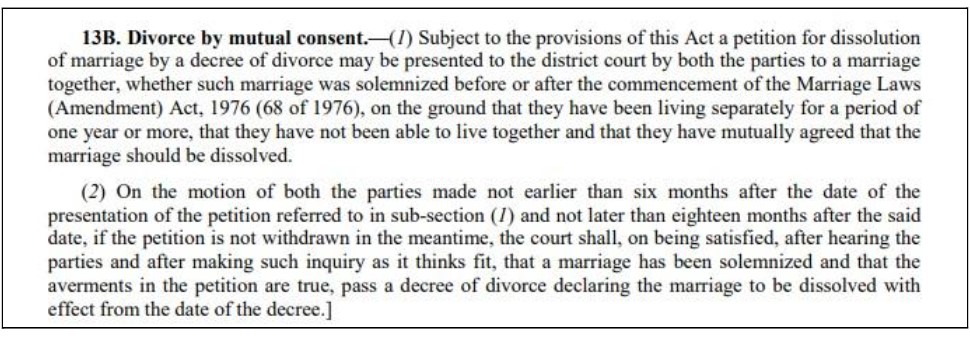

Section 13(B)(1) provides for the following conditions to be fulfilled when deciding on divorce.

- The parties have been living separately for a period of one year or more before the presentation of the petition.

- They have not been able to live together.

- They have mutually agreed to the dissolution of the marriage.

Subsection (2) specifies the time period. Clearly, the legislative intent behind incorporating sub-section (2) to Section 13-B of the Hindu Marriage Act is that the couple/party must have time to introspect and consider the decision to separate before the second motion is moved.

The objective of the cooling-off time is not to prolong an already failing marriage or the suffering of the parties when there is no likelihood of the union succeeding. Therefore, the court is not helpless in allowing the parties to pursue a better option, which is to obtain a divorce, once every effort has been made to save the marriage and there is no chance of reunion or cohabitation. The court has the discretion to dissolve such marriage without being bound by the procedural requirement to move the second motion.

Grant of divorce on the ground of irretrievable breakdown of marriage in exercise of jurisdiction and power under Article 142(1) of the Constitution of India.

The court looked at various judgements of the apex court regarding the grounds for divorce. In Naveen Kohli vs. Neelu Kohli, it was held that once serious endeavours for reconciliation have been made, but it is found that the separation is inevitable and the damage is irreparable, divorce should not be withheld. An unworkable marriage, which has ceased to be effective, is futile and bound to be a source of greater misery for the parties. The Court should take a decision that would ultimately be conducive to the interest of both parties.

Further, it is held that the grant of divorce on grounds of irretrievable breakdown of marriage is not a matter of right, but a discretion that must be exercised with greater caution and care, and that the marriage has irretrievably broken down is to be factually determined and firmly established.

On approaching the apex court and High Court using Article 32 & 226 of the Indian Constitution

On the question of whether the concerned parties can directly canvass before the apex court on the grounds of irretrievable breakdown of marriage, it is held that seeking such direct relief from this court cannot be permitted.

Delhi HC: The right of publicity cannot be infringed merely based on a celebrity being identified or the concerned party making commercial gain.

In Digital Collectibles PTE Limited and Ors. vs. Galactus Funware Technology Private Limited and Anr, the Delhi High Court held that the use of celebrity names, and images for the purposes of lampooning, satire, parodies, art, scholarship, music, academics, news, and other similar uses would be permissible as facets of the right of freedom of speech and expression and does not infringe on the right of publicity.

The single-judge bench headed by Justice Amit Bansal was referring to a suit on online fantasy sports (OFS). Plaintiff No. 1 is a Singapore-based business that operates under the trade name “Rario” in India and other countries, principally through its website and associated mobile applications. The first plaintiff’s business comprises developing an online marketplace where users from other parties may buy, sell, and exchange officially licensed “Digital Player Cards” of cricket players. The names, photos, and other facets of the players’ personalities are used on the Digital Player Cards on the Rario website. Plaintiffs 2 to 6 are Indian cricketers. Plaintiffs Nos. 2 to 6 have properly licensed and permitted Plaintiff No. 1 to use, among other things, their names, and pictures on the Rario Website under the terms of Player Services Agreements.

Defendant No. 1 operates a company called “Mobile Premier League” (hence “MPL”). The mobile application “Striker,” which is listed on defendant no.1’s mobile application “MPL,” is run by defendant no.2. The defendants operate their website under the trade name “Striker Club.” The defendants use NFT technology, the same as plaintiff No. 1, to validate player cards for the Striker Website. Contrary to plaintiff No. 1, the defendants lack permission or licenses from plaintiffs No. 2 through 6 to use their names, surnames, initials, images, or other identifying characteristics for commercial purposes.

The dispute arose when the plaintiff came to know of the ‘striker’ website and filed a petition on account of unlawful use of player marks amounting to unfair competition, unjust enrichment, breach of personality rights of plaintiffs No. 2 to No. 6, and unlawful interference with economic interests of the plaintiff.

The court looked at the submissions made by the parties and the references made to international and national legal developments. The court held that there must be a misappropriation of goodwill and reputation of a celebrity in selling a good/service to result in infringement of the right to publicity.

Further, the right of publicity cannot be infringed merely based on a celebrity being identified or the defendant making commercial gain, as is sought to be contended on behalf of the plaintiff.

Additionally, on the aspect of player attributes, the court held that publicly available information cannot be the subject matter of an exclusive license by the player in favour of a third party. Facts that are available in the public domain such as match information cannot be monopolized and even if a third party were to publish such information for commercial gain, no actionable right arises in favour of the plaintiffs.

Accordingly, the petition is in favour of the defendants and the plaintiffs failed to make out a case for the grant of interim injunction.

Karnataka HC: Loss of confidence is a subjective feeling; any termination must be based on objective set of facts and motivations.

The Karnataka High Court dismissed a petition seeking to set aside the decision of the Labour court that reinstated the workman, who was terminated based on ‘loss of confidence’. In Rudresha vs. The Management of M/s TVS Motor Company, the single-judge bench headed by Justice Suraj Govindaraj was hearing an appeal filed by TVS motor company against the labour court decision regarding the reinstatement of a workman.

The factual brief of the case is as follows. The workman is an ex-serviceman of the army and later joined the service with the employer as a Security Guard. The security officer filed a complaint that the workman did not show respect towards him by not saluting him, and in another instance, the workman neglected his duty of thoroughly checking the truckload, due to which one additional two-wheeler which had been loaded on the truck was allowed to pass. An internal enquiry found the workman guilty, and the disciplinary authority imposed the punishment of dismissal of the workman.

However, upon approaching the labour court, the Labour Court proceeded to set aside the punishment of dismissal and imposed the punishment of withholding two increments with cumulative effect and awarded 25% back wages.

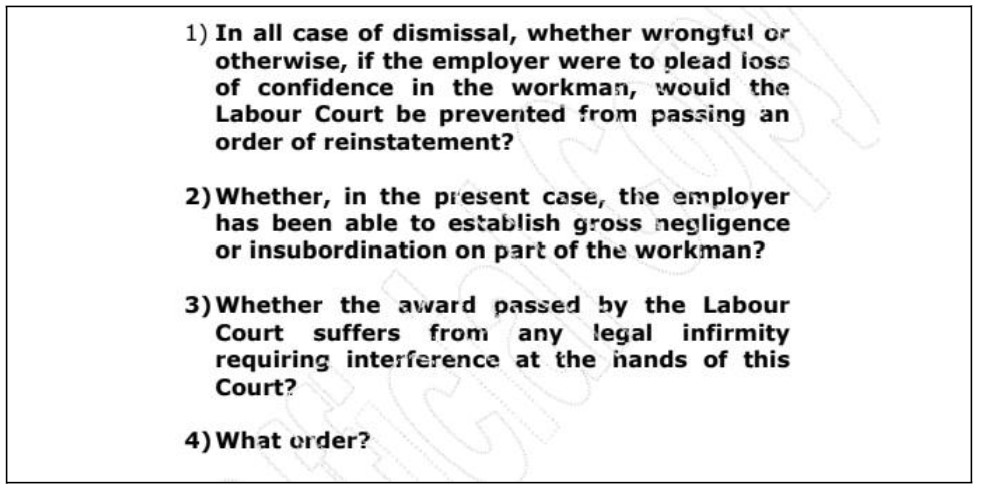

Looking at the submissions made by the concerned parties, the court summarized the points to be considered.

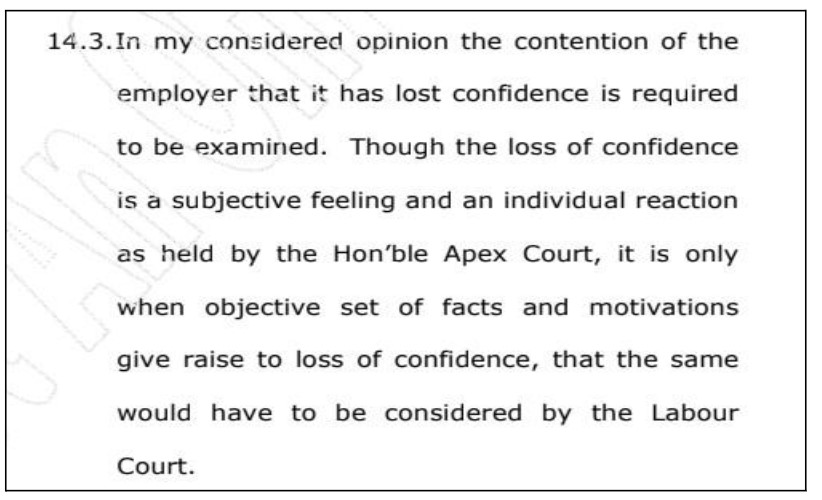

On the question of pleading loss of confidence in a workman, the court held that there cannot be such a straight jacket formula. In the present case, the contention of the employer losing confidence in the workman is liable to be rejected.

Further, the employer has not been able to establish gross negligence or insubordination on the part of the workman.

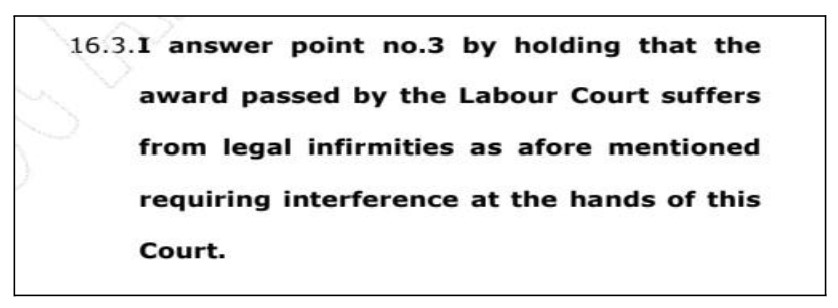

The High Court also held that the Labour court has erred in its judgement and the order suffers from legal infirmities.

Accordingly, the punishment imposed by the Labour Court in the award directing withholding of two annual increments for the period of two years, without cumulative effect, is set aside. Further, the employer is directed to settle all the dues of the workman within a period of 60 days from the date of receipt of a copy of this order.