One major feature of the recently passed farm bills is flexibility it provides the farmer to enter into agreements before the crop season. This is more akin to contract farming. But what are the other forms of agricultural marketing in India and how has contract farming fared in India so far? Here is a review.

During 2017-18, the central government released the model APMC (Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee) and contract farming Acts to allow and promote restriction-free trade of agricultural produce, competition through multiple marketing channels, and farming under pre-agreed contracts. The Standing Committee (2018-19) noted that many states carried out partial reforms only, on a pick-and-choose basis.

To this end, the central government promulgated three Ordinances on June 5, 2020: (i) the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020, (ii) the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020, and (iii) the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020. The three Ordinances together aim to increase opportunities for farmers to enter long term sale contracts, increase availability of buyers, and permits buyers to purchase farm produce in bulk. These were later passed by the Parliament & received the President’s assent in September 2020.

In previous articles, we have detailed the role of APMCs, the restrictions and limitations imposed by APMC laws as outlined by various committee reports, and the highlights of the three ordinances promulgated on 05 June 2020 along with the history of reforms to agriculture marketing.

In this article, we look at the contract farming scenario in the country and briefly go through the studies that have analysed the performance of various contract farming systems across the country.

What is Contract Farming?

It is defined as a system for the production and supply of agricultural, horticultural or allied produce by primary producers under advance contracts. Essentially, such arrangements include a commitment to provide a commodity of a type/quality, at a specified time, place, and price, and in specified quantity to a known buyer.

Contract Farming (CF) in India

Contract Farming is known by different variants like (i) centralised model which is company- farmer arrangement, (ii) out grower scheme which is run by government/public sector/joint venture, (iii) nucleus-out grower scheme involving both captive farming and CF by the contracting agency, (iv) multi-partite arrangement involving agencies other than the grower and the buyer, (v) intermediary model where middlemen are involved between the company and the farmer, and satellite farming referring to any of the above models. It varies depending on the nature and type of contracting agency, technology, nature of crop/produce, and the local and national context.

According to the Doubling Farmers’ Income (DFI) Committee Report, contract farming can address many traditional ills, such as lack of market connectivity, long chain of market intermediaries, ignorance about the buyer demands, etc. According to the report, this allows farmers to vertically integrate with specific and organised market channels. Contracts from bulk consumers can serve to offer regular and consolidated demand to farmers and an assured exchange against predetermined quality and quantity.

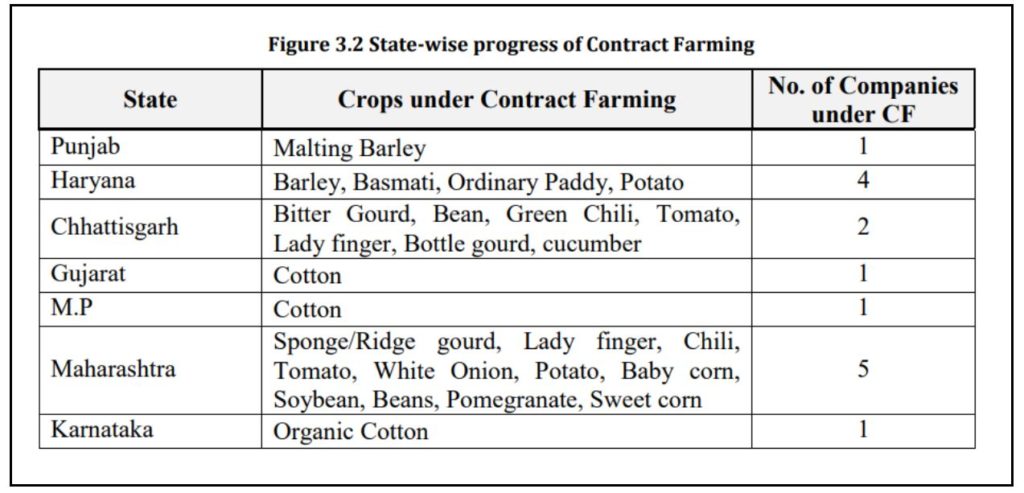

As per the DFI committee report submitted in August 2017, a snapshot of contract farming across different states is given below.

Contract farming is frequently extended to non-crop activities also. Poultry farmers for both eggs and broilers function under large enterprises in many States of the country particularly Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

What are the other alternative marketing systems?

The DFI Committee emphasises that though contract farming is not a sole solution for problems in agricultural marketing, it can very well be leveraged in certain regions and for specific crops for increasing farmers’ income. Contract farming is one of the many alternative marketing systems, such as:

(i) Direct marketing: where farmers directly transact with the produce consumers. These operates in two basic formats (i) Farmers’ Markets, and (ii) Direct sourcing from farmer’s field by processors (primary consumers). In these markets, no market fee is charged but service charges are collected from sellers. About 488 such farmers’ markets are operating in different States in the name of Apnamandis in Punjab, Haryana, Rythu bazaars in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Uzhavar Sandhai in Tamil Nadu, Shetkari Bazaars in Maharashtra and Raitha Santhe in Karnataka. As per a study on these bazaars, it is revealed that the producer’s share in the consumer’s rupee and marketing efficiency was more in case of Rythu bazars (Farmers’ market AP & Telangana) when compared to organised retail outlets and the least was in case of hawkers and petty vegetable enterprises.

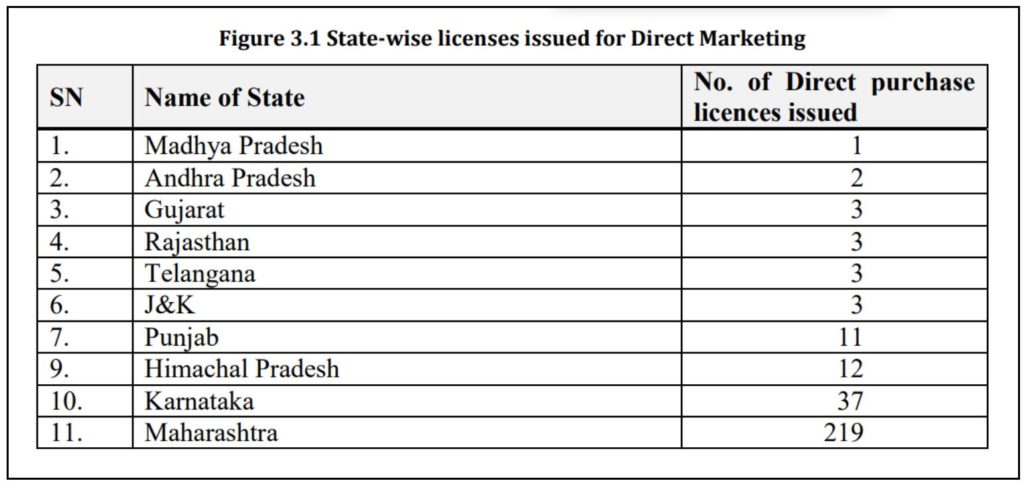

The other variant of direct marketing is by way of direct sourcing of the produce from farmgate by the processors, exporters, retail chain players, etc. Though recommended in the Model APMC Act & Rules, very few of States have issued such licenses for direct sourcing.

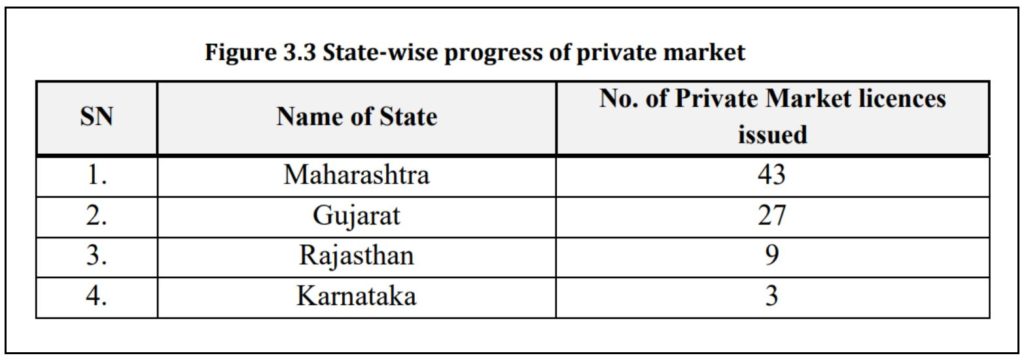

(iii)Private Wholesale Markets: According to the DFI Committee, 21 States/UTs have made enabling provisions for setting up of such markets and only 11 States have notified the rules thereunder to implement the provision.

(iv)Organised Retailing: The example of SAFAL (the fruit & vegetable marketing subsidiary of Mother Dairy) is mentioned as an example of indigenously organised retailing network. SAFAL operates in Delhi out of approximately 400 retail outlets and sells about 350 tonnes of fresh produce daily in Delhi-NCR markets. The growth in scale of private operators in food retail sector is also visible. Many Indian companies have organised the supply chain locally, from farm sources, for their own retailing requirements.

(v)Farmer producer organisations (FPOs): The aggregation of farmer into FPOs (cooperatives/SHGs/FIGs/Producer company), aid their integration into the supply chain, and in taking up roles traditionally by market intermediaries. Organising producers into formal management practices help to initiate collective decisions on cultivation to make the best use of market intelligence, offset fragmentation in land holding, and bring benefits of economies of scale.

(vi)Cooperatives in agricultural marketing: Cooperatives have achieved limited success over the years except those in the States like Maharashtra and Gujarat. Notable examples are in the dairy sector (GCMMF-AMUL) and in grapes (MAHAGRAPES) where collective operation has resulted in the reduction of transaction costs and improved the bargaining power of smallholders’ vis-à-vis foreign traders.

(vii)Food & agro-processing: The industry plays a vital role in employment generation and provides an assured demand to farmers, against predetermined quality parameters. The industry has specific requirements on crop types, food safety aspects and practices at farms and faces major constraints primarily due to the inadequate extension and linkage between production and processing.

Performance of Contract Farming in India

Most studies of the Contract Farming (CF) systems in India examine the economics of the CF system in specific crops, compared with that of the non-contract situation and/or competing traditional crops of a given region, e.g. in gherkins (hybrid cucumber) in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, tomato in Punjab and Haryana and cotton in Tamil Nadu.

Contracting agencies especially private, tend to prefer large farmers for CF because of their capacity to produce and supply better quality crops as they use efficient and business-oriented farming methods and possess various services like transport, storage, etc. They also supply large volumes of produce which reduces the cost of collection for the firm. Besides, they have capacity to bear risk in case of crop failure. On the other hand, small farmers are picked up by firms for contracts only when the area is dominated by them.

Only in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh, firms worked with small and marginal farmers due the nature of the crops (cucumber/gherkin, and broiler chicken) involved.

The factors which result in CF excluding small producers are: enforcement of contracts, high transaction costs, quality standards, business attitudes and ethics like non/delayed/reduced payment and high rate of product rejection, and weak bargaining power of the small growers. On the other hand, the organizers of CF find it costly to work with them due to their scattered location and smaller volumes.

Contracting agencies often impose eligibility conditions for contract production like certain land size, irrigated land, literacy level of the farmer, no non-contract crop production in the neighbouring fields, and certification which are discriminatory in terms of who can be a contract grower. In fact, several studies have shown that in CF, private agribusiness firms have less interest and ability to deal with small farmers on an individual basis and tend to prefer larger farmers for CF which leads to lower cost procurement for the firm.

In an article published in National Institute of Agricultural Economics and Policy Research in 2009, Sukhwinder Singh summarised various studies conducted across the country. It was found that contract production gave higher gross and net returns compared with that from the traditional crops. This was due to higher yield and assured price under contracts. But, in Punjab, except oilseed crops (hyola and sunflower), the net returns from contract crops were found to be lower than what farmers would have got from the wheat crop. However, production cost was also higher. But, in the case of cotton in Tamil Nadu, the contract growers had lower input cost, lower interest loans, faster payment for produce than in non-contract situation, and the crop insurance facility.

The studies in the states of Punjab and Haryana also reveal that contract growers faced many problems like undue quality cut on produce by firms, delayed deliveries at the factory, delayed payments, low price and pest attack on the contract crop which raised the cost of production. The contracts protected company interest at all costs to the farmer and did not cover farmer’s production risk e.g. crop failure, retained the right of the company to change price, and generally offered prices which are based on open market prices. This is a serious issue as even a significant premium over market price may not help a farmer if market prices go down significantly which is not uncommon in India.

The author emphasises that even though sustainability in CF is desirable to ensure its beneficial effects on growers and local economy, CF is only an instrument/means to agricultural development, not an end in itself. CF can wither away as a commodity market becomes efficient because it is only a response to a situation of market failure and depends on commodity/crop/sector dynamics which are liable to change, especially in a globalized and liberalized world.

In the same tone, the Doubling Farmers’ Income (DFI) Committee Report, provides a host of recommendations. Alongside provisions that increase opportunities for farmers to enter long term sale contracts, the committee strongly recommends focus on Gramin Agriculture Markets (GrAMs) scheme – to facilitate a new market architecture comprising organically linked village retail agricultural markets, alternative primary wholesale markets and export markets. Emphasis is also put on Pradhan Mantri Kisan Sampada Yojana under Ministry of Food processing Industries to complements the ongoing infrastructure support programs of the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, under Mission for Integrated Development for Horticulture.

Featured Image: Contract Farming in India