In this edition of court judgements review, we look at the Supreme Court’s judgements on judicial review, conferment of title in immovable property cases, Karnataka High Court’s judgement on POCSO Act, Madras High Court’s decision on removal of service, and Delhi High Court’s judgement on validity of arbitration clause in a contract after its novation.

Supreme Court: The scope of judicial review cannot be extended to examine the validity or reasonableness of an authority’s decision as a matter of fact.

In Indian Oil Corporation & Ors. vs. Ajit Kumar Singh & Anr., the Supreme Court held that the power of judicial review is limited to the decision-making process itself and not on the merits of the decision. Further, judicial review cannot be used to decide as if it is the first stage of case inquiry.

A two-judge bench comprising Justice Abhay S. Oka and Justice Rajesh Bindal was hearing an appeal petition against the judgement of the Patna High Court that set aside the punishment to an employee based on the departmental proceeding by re-admitting evidence at a stage of intra-court appeal. The brief facts of the case are as follows. Three bidders participated in the tender notice that the Appellant Corporation published on 30 June 2001, for the job of “Repair of Surface Drain and Tank Pad and Tank Nos. 235, 236 and 237 inside Refinery” (Barauni Refinery). On 24 April 2001, technical bids were opened.

The price bids, however, were not opened that day and were instead kept in K.C. Patel’s table drawer behind a lock with the notation “not opened today.” Two workers of the appellant, K.C. Patel and Ajit Kumar Singh had the keys in their possession. The Price bids were altered by altering the bid amount of one of the bidders while they were trapped within a drawer. The Central Forensic Institute’s investigation report provided evidence that the tampering had occurred. A chargesheet was sent to the accused to explain why a departmental inquiry should not be initiated against him.

After receiving the investigation report, the disciplinary authority imposed a punishment withholding the annual increments. An appeal filed before the appellate authority was also subsequently dismissed. Further, the respondent filed a writ petition before the High Court, which was dismissed by the Single Judge. However, later a division bench reversed the judgement of a single judge against which the present appeal is made in the Supreme Court.

Upon hearing the arguments of both parties, the apex court held that when exercising its judicial review authority, the court cannot decide as if the case is still in its early stages, as if the investigation is still ongoing, and as if the inquiry report is still being written. At the judicial review stage of a disciplinary procedure, evidence cannot be evaluated again as if the verdict in a criminal trial were being re-examined by the next higher court. It relied on the apex court judgement in Deputy General Manager (Appellate Authority) vs. Ajai kumar Srivastava, wherein the scope of judicial review has been clearly outlined.

Further, the apex court held that,

Accordingly, the appeal is allowed, and the judgement of the division bench of the High Court is set aside.

Supreme Court: An agreement to sell or the power of attorney are not documents of transfer and as such the right of title and interest of an immovable property do not stand transferred by mere execution of the same.

The Supreme Court, in Ghanshyam vs. Yogendra Rathi, held that the will and general powers of attorney (“GPA”) are not acceptable as title documents or as documents granting rights in any immovable property and mere execution of the same doesn’t render them the title.

A two-judge bench comprising Justice Dipankar Datta and Justice Pankaj Mittal was hearing an appeal petition filed by the defendant after having lost from all three courts. The brief facts of the case are as follows.

The owner of the “Suit Property” located in Delhi was Mr. Ghanshyam (“Appellant”). He and Mr. Yogendra Rathi (the “Respondent”) entered into an agreement to sell on 10 April 2002, for the sale of the suit property, and the Respondent paid him the full sale price. The appellant signed a will naming the Respondent as the beneficiary of the suit property on the same day. A general power of attorney was also signed by the appellant on the respondent’s behalf. The Respondent was given ownership of the suit property, but no sale deed was signed.

The respondent granted the appellant a three-month licence to use a section of the suit property. The appellant did not leave the property after the three-month grace period ended. The Appellant was sued by the Respondent in order to be removed from the Suit Property and to be compensated for any lost earnings. On the basis of the Agreement to Sell dated 10 April 2002, General Power of Attorney, memo of possession, receipt of payment of sale consideration, and a will date of 10 April 2002, the Respondent asserted his ownership of the suit property.

While the appellant did not dispute the execution of GPA and will, the trial court and the subsequent appeals before the High Court decided in favour of the respondent, and the appellant filed the present appeal before the apex court.

Upon hearing both sides, the apex court held that a plain reading of section 54 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, holds that an agreement to sell with payment of full consideration and possession along with irrevocable power of attorney and other ancillary documents is a transaction to sell even though there may not be a sale deed, are of no help and it does not override the specific provisions of law that require the execution of document of title or transfer.

The apex court relied on its judgement in Suraj Lamp & Industries Pvt. Ltd. vs. State of Haryana & Anr, and Delhi High Court’s decision in Imtiaz Ali vs. Nasim Ahmed, and G. Ram vs. Delhi Development Authority, wherein it was held that,

The court further held that, since the prospective purchaser has performed his part of the contract, he lawfully acquires possessory title which is liable to be protected in view of Section 53A of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882. The said possessory rights of the prospective purchaser cannot be invaded by the transferer or any person claiming under him.

The court further cautioned the use of will or GPA as a document of title and held that it is against the statutory law. Any such practice or tradition prevalent would not override the specific provisions of law which require execution of a document of title or transfer and its registration to confer right and title in an immovable property of over Rs.100/- in value.

Accordingly, the appeals are dismissed.

Karnataka HC: Non-reporting of POCSO offences snowballs; refuses to quash FIR against gynaecologist for failing to report sexual assault on minor.

The Karnataka High Court, in Dr. Chandrashekar T B vs. State of Karnataka, refused to quash an FIR against a gynaecologist for failure to report sexual assault on a minor. The Court held that non-reporting is a serious offence and has the potential to snowball into more serious offences.

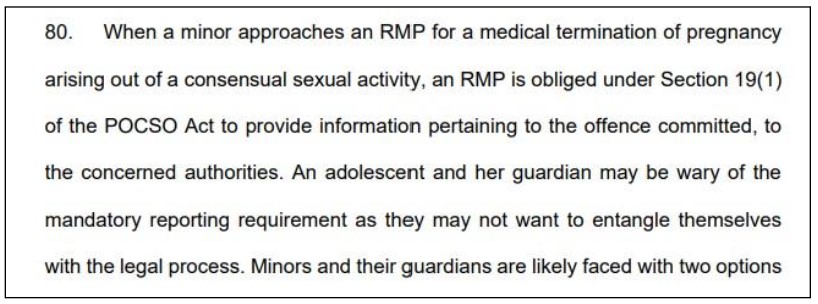

A single Judge bench headed by Justice M Naga Prasanna was hearing a petition calling into question the proceedings registered against the appellant for failure to report sexual assault on a minor. The allegation against the petitioner was that he has performed the act of medical termination of pregnancy on the victim who was then 12 years and 11 months old and had been subjected to sexual activity. The offence against the petitioner, in particular, was the one punishable under Section 21 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO Act).

The counsel for the petitioner argued that the doctor is reputed and had no malaise intention of doing anything that is alleged. The physical appearance of the victim was such that the victim seemed to be a major. The counsel pleased non-guilty relying on ignorance. The counsel for the state opposed the petitioner’s claims.

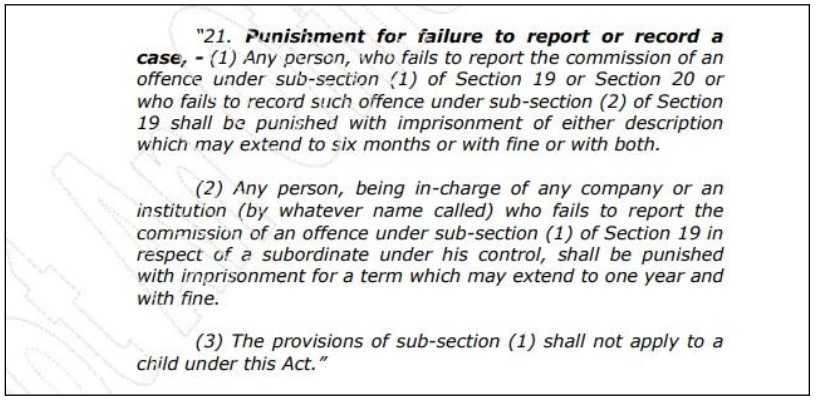

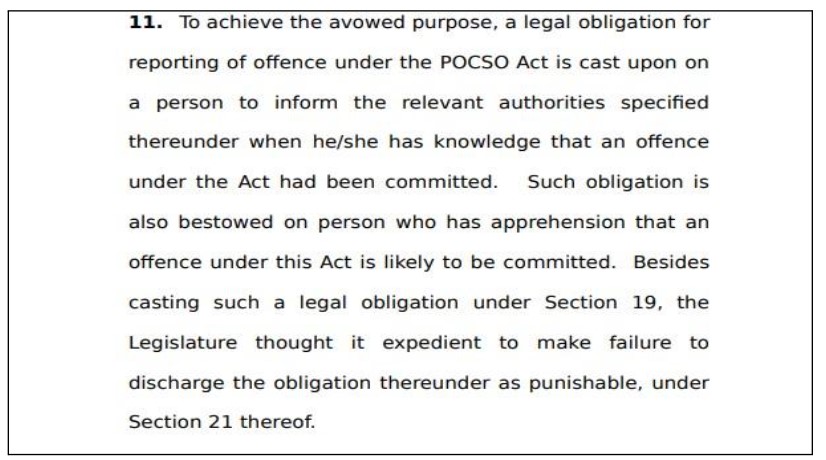

After hearing both sides, the court looked at section 21 of the POCSO Act. A plain reading of the section provides for the punishment for failure to report sexual assault on a minor. Further, section 19 clearly mandates that notwithstanding anything contained in the Code of Criminal Procedure, any person who has knowledge that such an offence has been committed shall report to the local Police or any other enumerated authority under clause (a) without any loss of time.

The court held that it was a serious dereliction of duty from the duty who commands a good amount of experience. Non-reporting of such cases will further snowball into serious offences. It relied on the judgement of the apex court in X .. vs. Principal Secretary, Health and Family Welfare Department, wherein it was held that failure to report would definitely ensure punishment.

Further, in the State of Maharashtra and another vs. DR. Maroti, the apex court held that reporting of offences under Section 19 and punishment for those offences under Section 21 must be of strict compliance to achieve the legal objectives of the POCSO Act.

Accordingly, the petition is dismissed and further directed the state to ensure strict compliance with Section 19 and reporting of offences particularly by doctors who indulge in medical termination of pregnancy of minors in extenuating circumstances.

Madras HC: The use of abusive words may not be a serious one to impose a capital punishment of dismissal from service.

In S Raja vs M/s.Hindustan Unilever Ltd and another, the Madras High Court held that the use of abusive language and showing a threat posture may not be construed to be grave in nature and the punishment of dismissal from service is disproportionate to the gravity of offence.

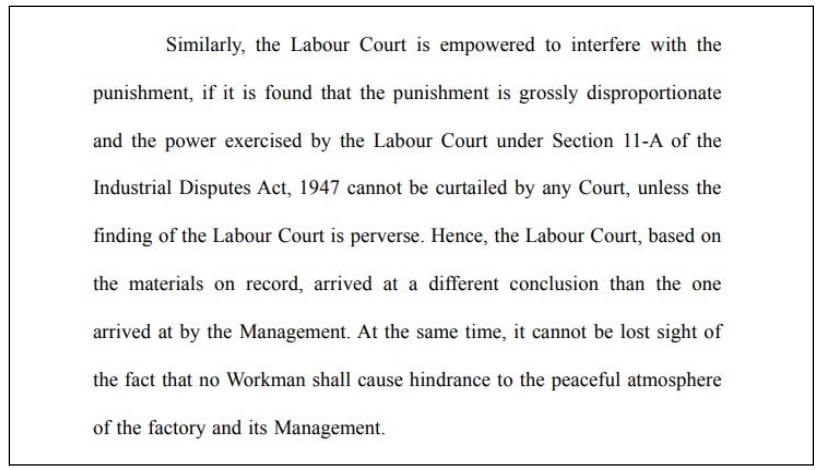

A two-judge bench comprising Justice S Vaidyanathan and Justice R Kalaimathi was hearing a petition filed by the Secretary of the Hindustan Lever Limited Tea Workers’ Welfare Union, by name S Raja. The petitioner argued that disciplinary action had been taken against him because he had spoken abusively to the Manager and Executives, and he had been fired from service following an investigation. When challenged before the Labour Court, it observed that the worker’s dismissal for conduct was extremely disproportionate and reinstated with continuity of service and 50% back wages.

The management challenged this order before the single-judge bench, which held that the order of labour court was not in consonance with the established legal principles. This order of the single-judge bench is challenged before the division bench.

Upon hearing both sides, the division bench of the Madras High Court held that while imposing the punishment, the authority concerned must consider the extenuating or aggravating situation as well as the past record of an employee. In the present case, since the workman was punished for a similar offence a decade back in 2001, it can be said that the misbehaviour is not frequent. Further, labour court has all the powers to interfere with punishment under section 11A of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 and this power cannot be curtailed by any court unless the finding of the labour court is perverse.

Further, the court held that we cannot expect a low-level employee to behave like Jesus so as to turn his other cheek for getting a voluntary slap.

Accordingly, the order of a single judge is interfered with, and the award of the labour court is modified with reinstatement and non-entitlement of back wages.

Delhi HC: If the novated agreement does not have an arbitration clause, the arbitration clause in the original agreement would expire with the novation.

The Delhi High Court, in B.L. Kashyap and Sons Ltd vs. MIST Avenue Pvt. Ltd, held that the arbitration clause in a contract perishes with the novation of the contract if the novated agreement does not contain an arbitration clause.

A single-judge bench headed by Justice Pratheek Jalan was hearing a challenge against the award by the tribunal regarding the non-arbitrability of the dispute. The facts of the case are as follows.

In 2014, the parties signed a Construction Agreement, which contained an arbitration clause (clause 20). It appears that certain disputes arose between the parties, which were resolved mutually, and the terms recorded in a Memorandum of Understanding dated 08 October 2015 [hereinafter, “the MoU”]. Admittedly, the MoU does not contain an arbitration clause at all.

It stipulated that the petitioner would receive specific payments, and in exchange would give over the assets and supplies to the respondent. When the agreed-upon payment was not made, a disagreement occurred between the parties. It is the contention of the petitioner that the respondent did not pay the sums payable under the MoU, as a result of which it was entitled to claim its dues under the 2014 Contract. Consequently, the petitioner invoked the arbitration clause contained in the 2014 Contract.

The central dispute between the parties is whether the arbitration agreement contained in the 2014 Contract survived the execution of the MoU.

Upon hearing both parties, the court relied on the apex court’s judgements in Union of India vs. Kishorilal Gupta and Lata Construction vs. Rameshchandra Ramniklal Shah, where it was held that the arbitration clause in a contract would perish with its novation.

On the question of whether the impugned award calls for interference on this account, the court relied on the judgement in Ssangyong Engg. & Construction Co. Ltd. vs. NHAI, wherein it was held that the interference by Courts with arbitral awards on the ground of patent illegality is permitted only in limited circumstances. On questions of contractual interpretation, the findings of the arbitral tribunal, being the domestic tribunal of choice, are generally to be respected, unless they are found to be irrational or perverse, in the sense that the interpretation is so implausible that no reasonable person could have arrived at it.

Further, under Section 34 of the Act, the court is not required to accord its own interpretation to the contractual documents, but only to assess whether the provisions are capable of the interpretation placed upon them in the impugned award.

Accordingly, the court held that the view taken by the arbitral tribunal does not call for interference under section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. The petition was dismissed accordingly.