The 2025 summer is expected to be warmer & harsher compared to 2024. While the number of heatwave-related deaths is an important metric for governments, significant discrepancies exist in data reported by different government agencies. The data of NDMA, MoES, NCRB, MoHFW do not match.

Year after year, global temperatures continue to break records. January 2025 saw global temperatures soaring 1.75°C above pre-industrial levels and 0.79°C more than the 1991-2020 average, according to the UN. While some regions experienced heavy rainfall and flooding, vast areas, including parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, faced drier-than-average conditions in January 2025. Despite the cooling influence of La Niña conditions for three consecutive years, 2025 is expected to be warmer than 2024, with the end of La Niña likely leading to a surge in global temperatures.

The trend underscores a broader pattern of increasing heat worldwide, with extreme weather events becoming more frequent and severe. In the Paris Agreement 2015, the international community set a goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. However, recent data reveals that this threshold has been exceeded in 18 of the last 19 months. The primary driver of these temperature spikes remains human activity—particularly the burning of fossil fuels—alongside factors such as deforestation.

A collection of datasets on heatwave deaths in India reported by different organizations is available on Dataful. A dataset on heatwave days recorded in India is also available.

Record temperatures reported in recent years

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has highlighted that global temperatures have remained persistently high in recent years, driven by ever-rising greenhouse gas concentrations and accumulated heat. This is evident from the “warming stripes” visualization used by WMO which uses simple coloured bars to show how the Earth has been heating up over time, with recent years turning darker red as temperatures keep breaking records.

It is only February, and Temperatures are already rising

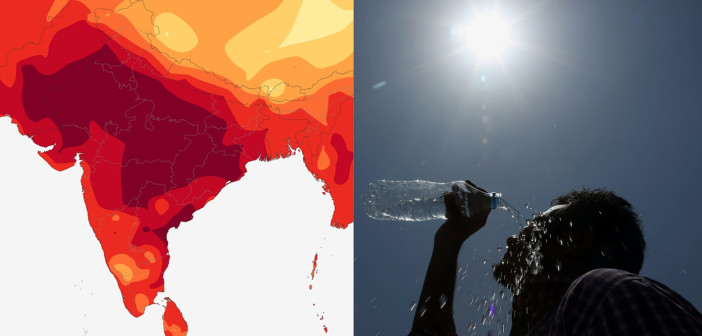

While record heat is no longer surprising, its consequences are becoming harder to ignore. In India as well, extreme heat waves are intensifying, leading to deadly consequences. Normally, summer lasts from March to June, but this year, just halfway into February, temperatures are already soaring in parts of the country.

According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), a heatwave is a period of excessively high air temperatures that can be dangerous to human health when exposed. It is defined based on temperature thresholds, either in terms of actual temperature or its departure from normal. In some places, it is also determined by the heat index, which considers temperature and humidity or extreme percentiles of temperatures.

Heat waves pose significant risks due to extreme temperatures, leading to heat stress, dehydration, and increased strain on the cardiovascular system. Vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, are particularly at risk. Severe heat-related illnesses, including heatstroke, can be life-threatening.

Given the impact of heat waves on human health, tracking fatalities caused by these extreme events is crucial for public health planning, risk assessment, emergency response, evaluating preventive measures, and adapting to climate change.

Though such data is critical, there are, however, notable inconsistencies in the data reported by different government agencies in terms of heatwave-related deaths.

MoES and NDMA publish different figures on deaths reported due to heat waves

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) publish data on the number of deaths due to heatwaves. NDMA’s data has been in different standalone reports and has been compiled for 2009 to 2022. MoES’s figures are picked up from those published by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) in its Envistats report. We collated the recent data from 2019 to 2023 from separate parliament responses by MoES since MoSPI stopped publishing the data on heat wave deaths in 2021. Since then, the Envistats report started publishing the figures on deaths due to heat stroke as given in the National Crime Records Bureau’s report, which has been discussed later in this story.

As visible in the chart below, there are significant discrepancies in the data published by both agencies. Available data indicates that MoES reported a total of 6,946 deaths during these 15 years (2009 to 2023). MoES reported 6,765 deaths between 2009 and 2022 while NDMA reported almost twice the number of deaths – 11,069 during the same period.

Even though there are huge discrepancies in the figures reported, the overall trend suggests that the deaths due to heat waves peaked in 2015 and have declined considerably since then. It was around this time that states started implementing heat action plans. Ahmedabad was the first city in South Asia to develop and implement such a plan.

Further, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), between 1992 and 2020 (in 28 years), a total of 25,692 deaths occurred due to heatwaves in India. About one-third or 8,716 deaths took place between 2011 and 2021. However, during the same 28-year period, MoSPI reported 13,237 deaths, nearly half of that reported by WMO. Between 2011 and 2021, MoSPI reported 6,252 deaths, about two-thirds of that reported by WMO for the said period.

NCRB reported 4,000 more deaths than NDMA between 2009 and 2022, even though both are under the same ministry

The NDMA is an autonomous body under the Ministry of Home Affairs. Another agency that operates under the same ministry is the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). NCRB, in its annual Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India (ADSI) report publishes the number of deaths due to heat strokes. It is based on data furnished by state police departments. The Bureau uses dedicated software for digital data collection, validation, and compilation at various levels, with inbuilt checks ensuring accuracy.

According to the NCRB reports, a total of 15,020 deaths due to heat strokes took place between 2009 and 2022, about 4,000 more than that reported by the NDMA. Until 2013, the data produced by NCRB matches with the one published by NDMA. However, since 2014, the values reported by NCRB are very different from those reported by NDMA.

Similar Question, Different Answers by the MoES

While the MoES has been referring to the numbers reported by NCRB while responding to the questions in Parliament, this is not always the case. For instance, in a response given in July 2023 regarding deaths that took place due to heat waves that year, the Ministry stated that “figures for the year 2023 are not yet updated by the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs.”

However, MoES provided the data on deaths due to extreme weather events in response to a question in December 2024 which also included data about deaths due to heat waves for 2023. The sources for this data were mentioned as media reports and reports from government Disaster Management Authorities. Further, in another question answered in August 2024 about deaths due to heat waves, the Ministry once again referred to the NCRB figures and provided data only up to 2022.

Health Ministry started capturing Heat related illnesses and deaths data since 2015

Since 2015, the Union Health Ministry started collecting data on morbidity and mortality due to Heat-related illness (HRI) through the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP) from heat-vulnerable States/UTs during the summer season. Initially, it recorded data on HRI from April – July from 17 states. Since 2019, it has covered the period from March to July every year from 23 states. It captures heatstroke cases and deaths due to suspected/confirmed heatstroke.

The data from the Health Ministry on deaths due to heat waves/stroke-related illnesses matches the figures published by the NDMA for the period from 2015 to 2022. However, according to a report from the Health Ministry, there were 189 confirmed heat stroke deaths in 2023 and 161 in 2024 while the figures as per a parliament response of the ministry from July 2023 were 264 deaths due to heat wave in 2023 as of 30 June 2023. Again, these figures are different from those of deaths due to heat strokes reported by NCRB.

The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) under MoES also publishes data on deaths due to heat waves in its annual report. IMD reported a total of 3568 deaths between 2015 and 2023 while MoES reported 3740 during the same period in the MoSPI’s Envistats report.

Discrepancies even in state-level data

Similar discrepancies are observed at the state level too. For instance, according to a press release of MoES (Parliament response), a total of 1,369 deaths were reported in Andhra Pradesh in 2015 while NCRB reported 654 deaths in Andhra Pradesh in 2015. According to the Health Ministry, 1422 deaths were recorded in Andhra Pradesh in 2015.

Various agencies could be under-reporting the data

Studies have also estimated that around 1,116 deaths annually could be attributed to heatwaves, highlighting the possibility of under-reporting in India. Additionally, heat can exacerbate existing health conditions, potentially leading to death. For instance, extreme heat can strain the cardiovascular system, increasing the risk of heart attacks and strokes, particularly among vulnerable populations such as the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures can also lead to severe dehydration, kidney failure, and complications in individuals with respiratory illnesses. Thus, not all deaths are necessarily directly attributable to heat, making it challenging to capture the full impact of extreme temperatures in official records.

Some of these reasons could be causing the significant discrepancies in heat wave-related death data reported in India. Varied methodologies and definitions used by different agencies could be another reason. Even within the same ministry, different organizations have reported differing figures, reflecting inconsistencies in data collection and classification. Additionally, the use of varied terminology—such as deaths due to heat waves, heat-related illnesses, or heat strokes—adds to the confusion, as each term carries a distinct meaning. It is high time that India works on standardizing definitions and data reporting practices as it is crucial to ensure clarity, accuracy, and better-informed policy responses to extreme heat events, which are on the rise.