The Supreme Court recently directed political parties to disclose reasons for selection of candidates with pending criminal cases. However, like the previous directions of the Supreme court, these are not really making any difference. Here is why.

In a recent judgement passed by the Supreme Court (SC) on 13 February 2020 in Public Interest Foundation vs Union Of India, political parties have been directed to publish criminal antecedents of contesting candidates along with reasons for fielding each one of these candidates, notwithstanding their ‘winnability’. The Election Commission of India (ECI) has also issued a directive to implement the apex court’s orders concerning criminal antecedents of candidates.

While the judgement is a step towards ensuring accountability and transparency in politics, the SC has issued similar directions over the past few years. In this article, we take a stock of the major judgements delivered by courts, important reports on electoral reforms and persistent challenges against the growing criminalisation of politics in India.

Data on Criminalisation of Politics

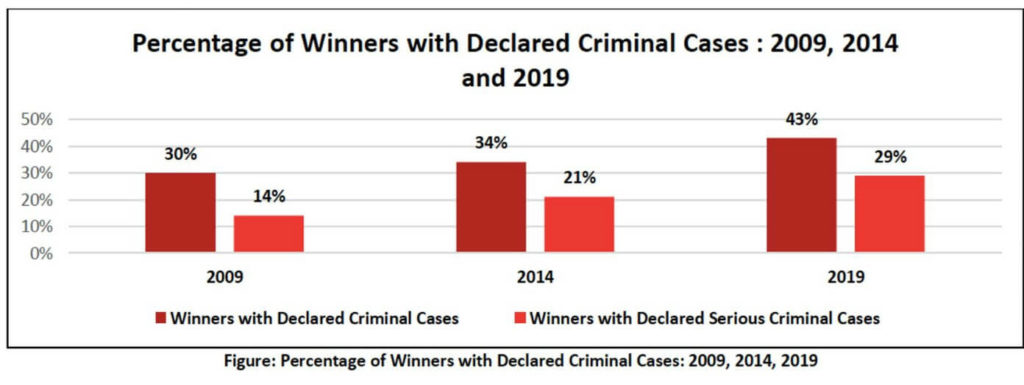

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), established in 1999, has been conducting detailed analysis of the backgrounds of candidates contesting elections. ADR has conducted Election Watches for almost all state and parliament elections in collaboration with the National Election Watch. In ADR’s report for Lok Sabha 2019 elections titled ‘Analysis of Criminal Background, Financial, Education, Gender and other details of Winners’, the trend in winners with declared criminal cases has been recorded for 3 consecutive Lok Sabha elections.

Lok Sabha 2019: Out of the 539 winners analysed for Lok Sabha 2019, 233 (43%) Winners have declared criminal cases against themselves. 159 (29%) winners have declared serious criminal cases including cases related to rape, murder, attempt to murder, kidnapping, crimes against women etc.

The chances of winning for a candidate with criminal cases in the Lok Sabha 2019 elections were 15.5% whereas for a candidate with a clean record it is 4.7%.

Lok Sabha 2014: Out of the 542 winners analysed during Lok Sabha 2014 elections, 185 (34%) winners have declared criminal cases against themselves. 112 (21%) winners have declared serious criminal cases including cases related to murder, attempt to murder, communal disharmony, kidnapping, crimes against women etc.

The chances of winning for a candidate with criminal cases in the Lok Sabha 2014 elections were 13% whereas for a candidate with a clean record it is 5%.

Lok Sabha 2009: Out of 521 winners analysed during Lok Sabha 2009 elections, 158 (30%) winners had declared criminal cases against themselves. 77 (15%) winners had declared serious criminal cases against themselves.

During the last few decades, several committee reports have also pointed out the growing criminalisation of Indian politics and its implications. Starting with Goswami Committee on Electoral Reforms (1990) that addressed the need to curb the growing criminal forces in politics, the report of Vohra Committee Report (1993) reveals several alarming and deeply disturbing trends. It referred to several observations made by official agencies, including the CBI, IB, R&AW, who unanimously expressed their opinion on the criminal network which was virtually running a parallel government. The Committee also took note of the criminal gangs who carried out their activities under the aegis of various political parties and government functionaries. The Committee further expressed great concern regarding the fact that over the past few years, several criminals had been elected to local bodies, State Assemblies and the Parliament.

On various occasions, the courts have also recognised that the nexus between politicians, bureaucrats and criminal elements in our society has been on the rise, the adverse effects of which are increasingly being felt on various aspects of social life in India. In the 18th Report presented to the Rajya Sabha on 15 March 2007, by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on Electoral Reforms acknowledged the existence of criminal elements in the Indian polity which hit the roots .

Major Judgements on Voter’s Right to Know

| Date of Judgement | Highlights of the Judgement |

|---|---|

| 13 February 2020 Public Interest Foundation v. Union of India | Various litigants filed contempt petitions against the EC for not monitoring whether political parties were complying with the directions issued in the 2018 Public Interest Foundation v. Union of India judgement. The Bench re-iterated the Court’s 2018 directions and directed the Election Commission to report to the Supreme Court any non-compliance by political parties. It also directed political parties to publish additional information like reasons for selecting a candidate with pending criminal cases. |

| 25 September 2018 Public Interest Foundation v. Union of India | First, the SC decided that it cannot disqualify candidates, against whom criminal charges have been framed, from contesting elections. The Court recommended that Parliament make laws to curb the increasing criminalisation of politics. Second, the SC issued directives to the Election Commission, which in turn mandated the political party as well as candidate with criminal antecedents to publish information on website, newspapers and through television channels on three occasions during the campaign period, before the election. Refer to Factly’s earlier article for further details. |

| 13 March 2003 People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India | Voters have a fundamental right to know relevant information about candidates. A section of law (Section 33B of PRA) stating that candidates could not be compelled to disclose any information about themselves other than their criminal records was unconstitutional. |

| 2 May 2002 Association for Democratic Reforms v. Union of India; and People’s Union of Civil Liberties & Anr. v. Union of India & Anr. | The verdict established the filing of affidavits by candidates as the right of the voter. The SC held that the right to information – the right to know antecedents, including the criminal past, or assets of candidates – was a fundamental right under Article 19 (1) (a) of the Constitution and that the information was fundamental for survival of democracy. It directed the Election Commission to call for information on affidavit from each candidate seeking election to Parliament or the State Legislature as a necessary part of the nomination papers on: whether the candidate has been convicted / acquitted / discharged of any criminal offence in the past – if any, whether the candidate was accused in any pending case of any offenses punishable with imprisonment for two years or more, and in which charge was framed or cognizance taken by the court. |

What determines Electoral Disqualifications?

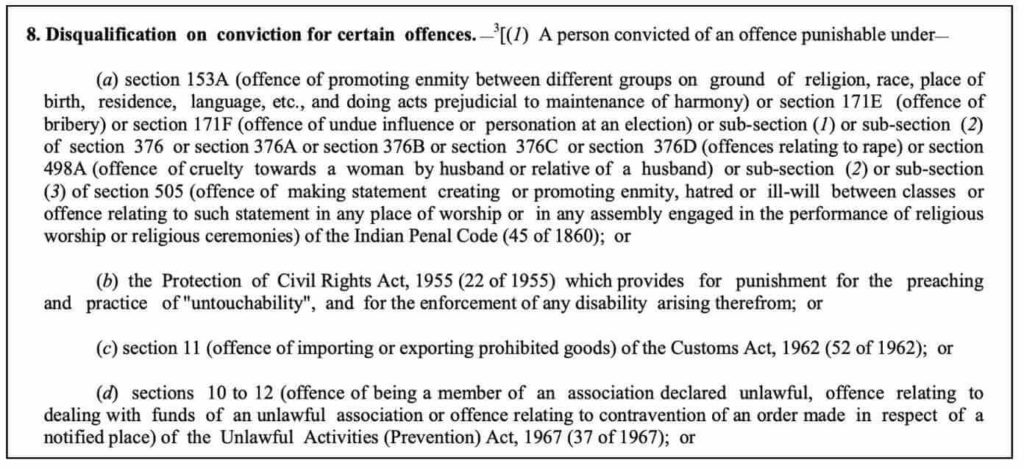

Section 8 of The Representation of People Act, 1951 (RPA) outlines criteria for disqualification of contesting candidates from membership to Parliament and State Legislature. The section elaborates on the criteria for disqualification if the candidate is convicted for certain offences such as corruption, rape, terrorism, etc.

In 1999, the 170th Law Commission Report on Electoral Reforms was the first to suggest that a new Section 4A be added to the Representation of the People Act, 1951 mandating that a person shall be ineligible to contest elections unless they file an affidavit declaring their assets along with a declaration whether charges had been framed against them by a criminal court.

In 2002, the Association of Democratic Reforms petitioned the Court to have the above recommendation implemented, among others. In pursuance of the historic judgment, the Election Commission issued directives to the effect that failure to file an affidavit containing the above details would result in the nomination paper being deemed incomplete within the meaning of Section 33(1) of the RPA and, therefore, lead to the rejection of candidate’s nomination papers.

Later that same year, the RPA was amended to add Sections 33A and 33B. Together both the section implied that the no candidate shall be liable to disclose any information other than their criminal antecedents. In other words, directions of the Supreme Court regarding further disclosure of assets and educational qualifications stood reversed by this amendment. In 2003, Section 33B was struck down as unconstitutional in PUCL v. Union of India as it imposed a blanket ban on the dissemination of information. The candidates now had to furnish information relating to all pending cases in which cognizance has been taken by a Court, his assets and liabilities, and educational qualifications.

After the 2002 judgement made it mandatory to disclose all criminal antecedents, the practice of leaving blank spaces or filling incorrect information in affidavits and nomination papers became commonplace. In order to avoid perjury, candidates would not furnish any information on crucial questions relating to criminal history or assets. This practice was challenged later. As stated in the EC’s Report no. 244 on Electoral Disqualifications, while the 2003 PUCL judgment clarified the obligations of a candidate with respect to the furnishing of information, it was less clear on the consequences if the information provided happened to be false. It held that a Returning Officer could not reject nomination papers on the ground that candidate information was false. As a result of this finding, the Election Commission ordered its earlier directive on the rejection of nomination papers non-enforceable.

It instead directed that if a complaint is submitted regarding furnishing of false information, the Returning Officer should initiate action to prosecute the candidate under Section 125A of the RPA which provides penalty for filing false affidavits. However, Section 125A of the RPA has not been included in the list of offences under Section 8 of the RPA – which outlines criteria for disqualification of election candidates. There is no readily available data on the count of candidates prosecuted for filing false information, though there seem to be no reported conviction on this crime, the report highlights.

Therefore, filing of false information, even if proved under Section 125A, is not a ground for setting aside the election, or for further disqualification. This matter was in question in several cases, such as Nand Ram Bagri v. Jai Kishan (7 May 2013, Delhi High Court), Arun Dattaray Sawant v. Kishan Shankar Rathore (9 May 2014, Bombay High Court), Krishnamoorthy v. Siva Kumar (5 February 2015, Supreme Court), among others. From these judgements, the report argues that one can conclude the following:

- If details are omitted in the nomination papers, it is fit to be rejected.

- If information is believed to be false, prosecution under Section 125A is possible, however the consequences upon conviction are unclear. While the Bombay High Court in Arun Dattaray Sawant maintains that filing of false affidavit is a ground for setting aside the election, other High Courts have taken a contrary view. The filing of false affidavits can therefore at most lead to six months imprisonment and fine, without altering the election verdict or the candidate’s ability to contest future elections.

This undermines the value of candidate disclosures – due to the lack of consequences, candidates have little incentive to provide accurate information. It has been noted by the EC that candidates have repeatedly failed to furnish information, or grossly undervalued information such as the quantum of their assets.

Does the 2018 judgement propose any major changes?

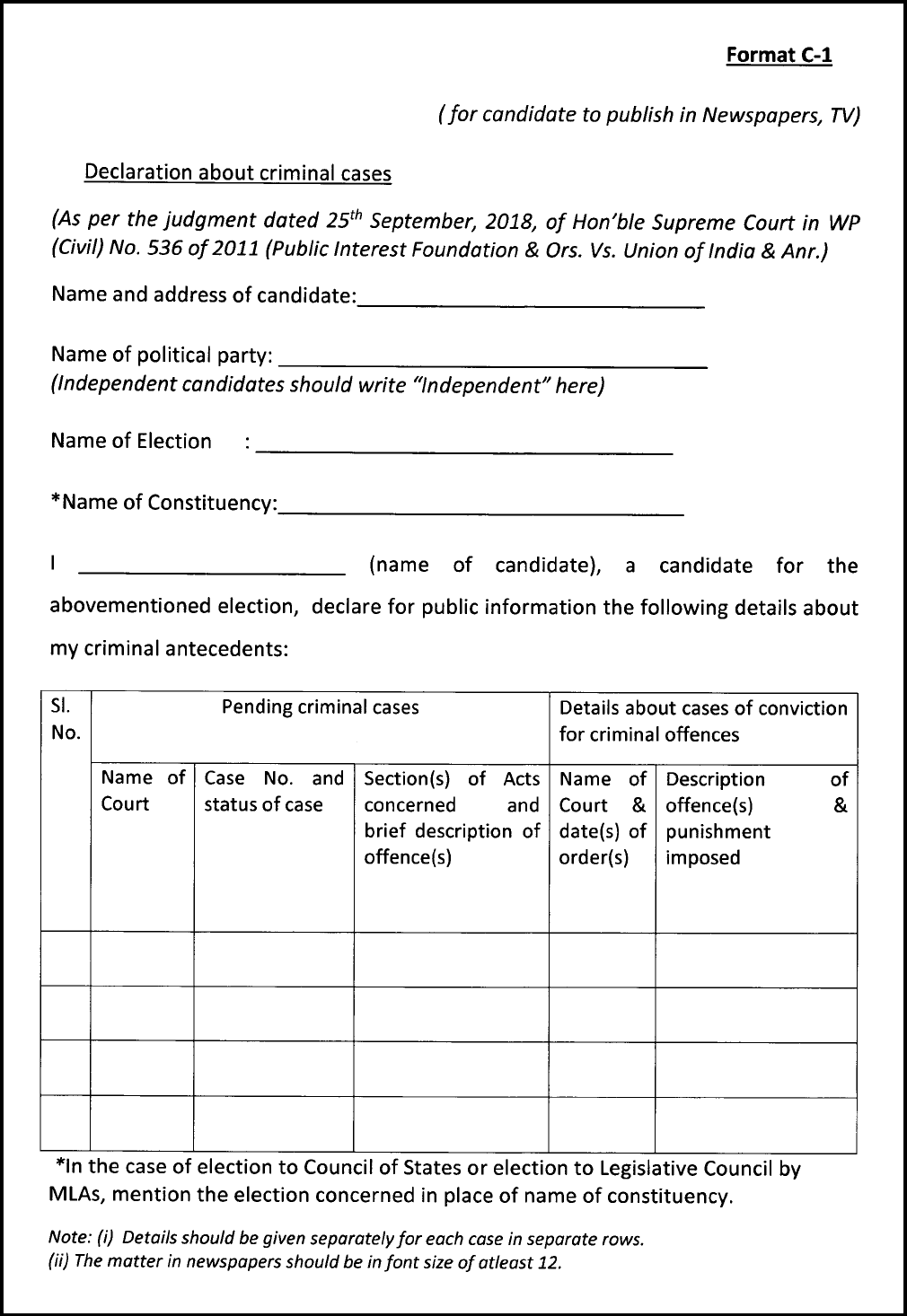

The 2018 judgment issued the following five ‘directions’ to the Election Commission:

- A candidate must fill in the prescribed form.

- The candidate must fill in bold letters that he is implicated in some crime.

- The candidate must inform his party that he is implicated in some crime.

- On receiving information from a candidate of his criminal antecedents, the party must put this information on its website.

- The criminal antecedents should be published by the candidate and his party in newspapers, which are widely circulated in the locality. The information must be published in a local as well as a national newspaper as well as the parties’ social media within 48 hours of selection of candidate or two weeks before the first date of filing on nominations, whichever is earlier.

It is important to note that, in the 2018 judgement, the Court did not entertain the petitioner’s second request, which called for Section 125A to fall under the ambit of Section 8 of The Representation of People Act. In other words, to automatically disqualify candidates who file false affidavits. The Court did not entertain the plea citing separation of powers and recommend the parliament to make a law that prevents candidates accused of serious crimes from entering politics.

While candidates have been required to submit details of their criminal cases to the poll panel through an affidavit from the 2002 judgement onwards, the 2018 judgement expands the scope by making it necessary to publish this information on party website, newspaper and television channel.

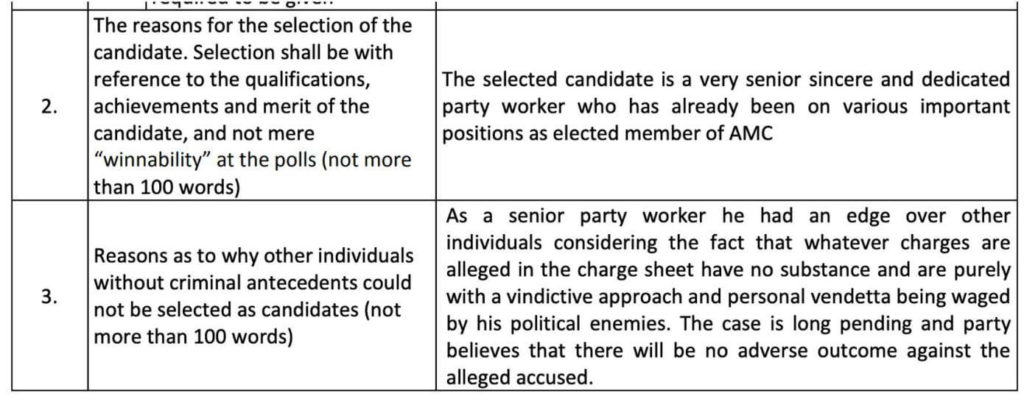

In the current 2020 judgement, the only new addition is that now political parties have to state reasons for fielding candidates with criminal background, other than ‘winnability’.

However, the judgement or the EC did not outline how the publication of information will be monitored or ensured that it is followed rigorously. The enforceability of such orders by the apex court has remained a complex matter due to the lack of well-defined parameters to ensure compliance. Whether political parties will publish the criminal antecedents of their candidates on their websites, local and national newspaper, and social media accounts is a moot point.

Generalistic explanations are the order of the day

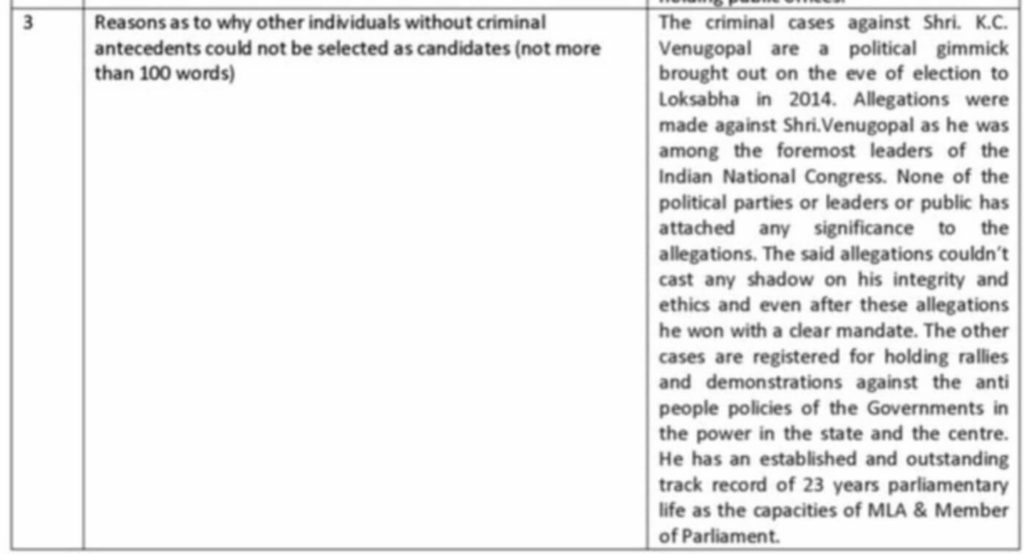

While the idea is to push for accountability from political parties, the 2020 judgement adds little value to the existing pool of available information and provides avenue for vague and generalistic explanations. For instance, let’s take a look at recent publication of mandated C-7 forms by different political parties. There is a common thread in all the published forms – BJP’s publication of Amit Popatlal Shah’s form for Rajya Sabha elections, INC Rajasthan’s publication of K.C. Venugopal’s form for Rajya Sabha elections, INC Madhya Pradesh’s publication of Digvijaya Singh’s form for Rajya Sabha elections, and INC Jharkhand’s publication of Shahzada Anwar’s form for Rajya Sabha elections. All the publications have stated that the concerned candidate is experienced, suitable, and worthy of the given candidature owing to their experience and stature. On the question of why these candidates with criminal background were chosen over other candidates without criminal background, all the answers have highlighted that the criminal charges are politically motivated.

The new information adds little value

These answers add little value to the existing pool of information available on the criminal antecedents of contesting candidates. The most important issues of submission of inaccurate and incomplete information by contesting candidates is likely to improve with wider publication of candidate information on various platforms. While the recent judgement is the right step towards increasing accountability and transparency, reduction in criminalisation of politics and the continued challenge of monitoring and compliance have not been addressed.