The Supreme Court in February this year directed political parties to disclose reasons for selecting candidates with pending criminal cases instead of the cleaner candidates. The upcoming Bihar elections will be the first major election to be held after these new directions. Will the political parties disclose the real reasons for selecting candidates with pending cases?

On 13 February 2020, the Supreme Court (SC) delivered a judgement directing all political parties to upload details of pending criminal cases against candidates contesting on the party ticket, on their website. The reason for selection of the candidate along with details of pending criminal cases should also be made public by the political party. Even the Election Commission of India (ECI) directed the Chief Electoral Officers (CEOs) all the states and UTs to implement the Supreme Court’s order. The Bihar Legislative Assembly elections, scheduled to take place in October 2020, would be the first one following the Supreme Court’s order in February 2020.

However, this is not the first time that the apex court delivered such an order. In the past few years, the Supreme Court passed orders concerning declaration of criminal antecedents of contesting candidates citing the increased criminalization of politics in the country.

‘Right to know’ the Contesting Candidate’s antecedents was upheld by SC in 2002

In Union of India Vs Association for Democratic Reforms and another; with People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India and another, the Supreme Court in 2002 held that the citizens have a right to know about public functionaries. The court maintained that ‘right to know’ contesting candidate’s antecedents was a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19 (1)(a) since such rights include the right to hold opinions and acquire information for citizens to be adequately informed in order to form those opinions. The Court added that a successful democracy strives toward ‘aware’ citizenry. Misinformation, or non-information will create uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce. If non-informed or mis-informed voter castes vote, it will definitely affect democracy.

The SC directed the ECI to issue necessary orders to collect details regarding the background of candidates contesting elections to Parliament and State Legislatures, including

- criminal charges and convictions in the past

- whether the candidate was punished in the past with fine or imprisonment

- any pending case/cases in which they have been accused

- the details of assets of candidates and their spouses

- their liabilities

- and the candidate’s educational qualification.

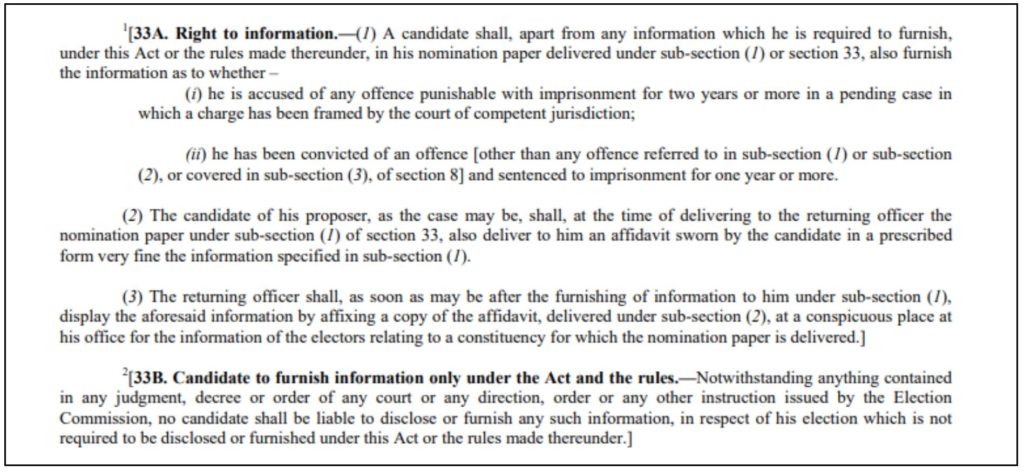

Sections 33A and 33B were inserted in ‘The Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA 1951)’, in 2002 following the SC judgement. Section 33A states that information regarding criminal antecedents of contesting candidates such as if he has been accused of any offence with two years’ imprisonment or more, or if he has been convicted in any other offence and sent to prison for at least one year, should be disclosed. These are to be disclosed in Form 26 in the form of a self-sworn affidavit. Section 33B of the RPA 1951 stated that the candidates could not be forced or compelled to disclose any information about themselves except what is required under the act.

Section 33B of RPA was struck down by SC in 2003

Later in March 2003, in People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India and another, Section 33B was found to be problematic on several grounds. The SC struck down Section 33B since it would otherwise nullify the 2002 landmark verdict of the SC. Thus, the candidates had to submit information relating to all pending cases in which cognizance has been taken by a Court, in addition to the details regarding assets, liabilities and educational qualification.

Despite these judgements, candidates continued to leave blank spaces or filled false information in affidavits. Though the judgement in 2003 clearly listed the information that needs to be submitted, there was not much clarity or details given on what should be done if the information provided is false. Returning Officer could not reject nomination papers if the information provided was false.

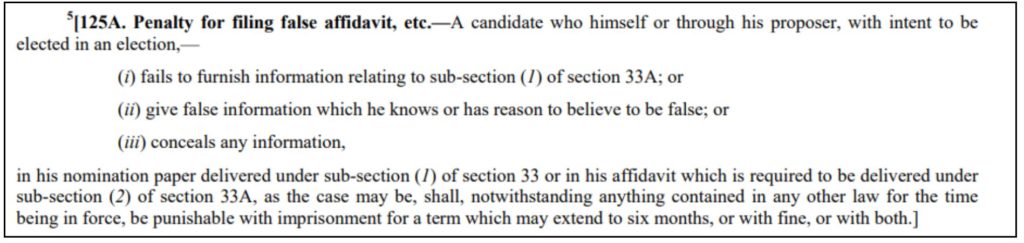

Filing false information, concealing information or not filling information does not result in disqualification of candidate

Under Section 125A of RPA also inserted in 2002, a candidate who does not furnish information regarding pending criminal cases, conceals it, or gives false information, will be liable for imprisonment up to six months and/or a penalty. The offence under Section 125A does not fall in the ambit of Section 8 of the RPA which lists out criteria for disqualification of contesting candidates. This implies that those filing false information or concealing information cannot be disqualified. The matter was discussed in several other cases. Arun Dattaray Sawant v. Kishan Shankar Rathore in 2007 in Bombay High Court, Nand Ram Bagri v. Jai Kishan in 2013 in Delhi High Court, and Krishnamoorthy v. Siva Kumar in 2015 in Supreme Court are some such cases.

Affidavits with blank spaces may be rejected

Finally in Resurgence v. ECI, the SC stated that if an affidavit is filed with blank particulars, it renders the entire exercise of filing affidavits futile, and infringes the fundamental rights of citizens under Article 19 (1). The Returning Officer should remind the candidate to fill the blanks. Yet, if the blanks are left unattended, the nomination is fit to be rejected.

Directions by SC in 2018 to promote transparency and flow of information

In Public Interest Foundation v. Union of India, the SC in 2018 had to decide whether members of legislative bodies should be disqualified when criminal charges are filed against them. Disqualification of contesting candidates from membership to Parliament and State Legislatures is dealt with under Section 8 of the RPA which states that the candidate will be disqualified if convicted for certain offences such as rape, corruption, terrorism, etc. The SC decided not to debar candidates with pending criminal cases from contesting elections. However, SC gave certain directions to promote transparency and flow of information about contesting candidates and pending criminal cases against them. A few important directions include

- Form 26 filed by contesting candidates must have details of pending criminal cases against the candidates in bold.

- If the candidate is contesting election on the ticket of a party, they should inform the party about the pending criminal cases against them

- Concerned party must publish information of candidates with pending criminal cases in website and at least thrice in television channels and newspapers before election.

Political Parties to disclose reasons for selection of candidates with pending criminal cases

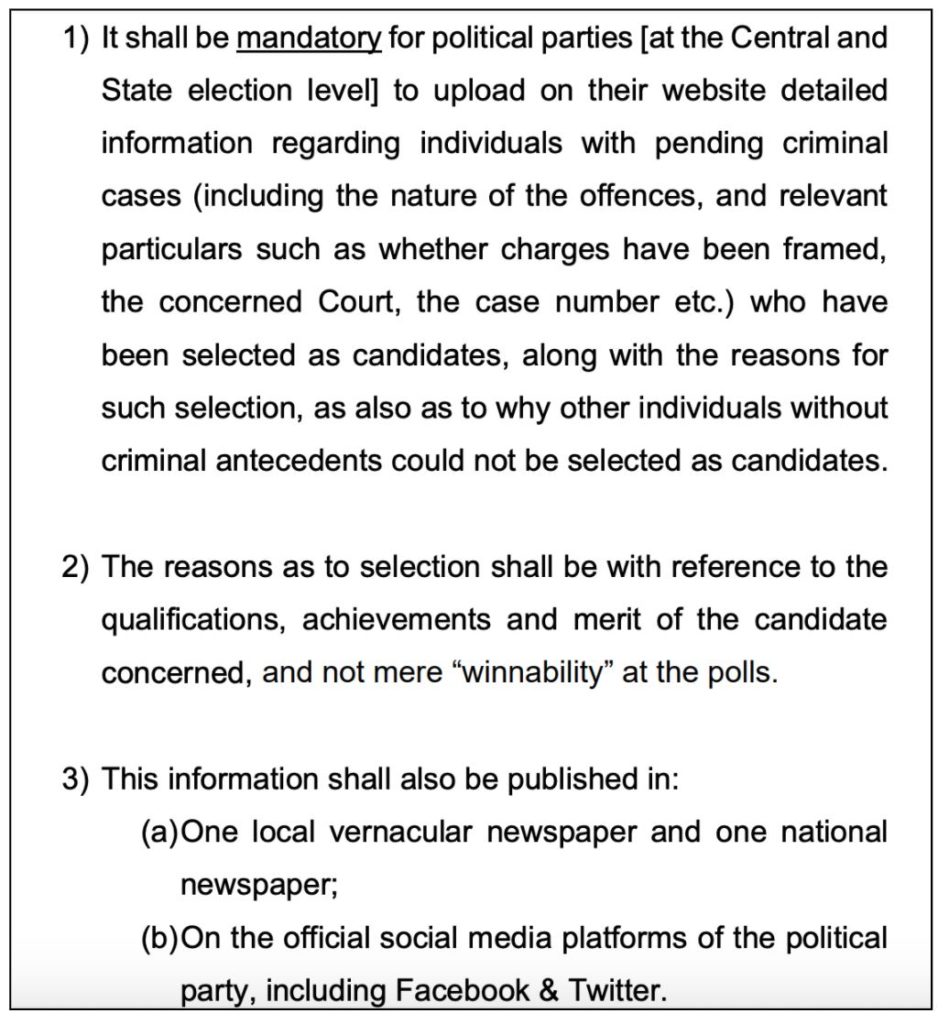

In Rambabu Singh Thakur v. Sunil Arora, the SC in February 2020 gave a series of directions to check the criminalization of politics. The Court had observed that in 2004, 24% of MPs had pending criminal cases against them. In 2009, the same was 30% and in 2014, it went up to 34%. In 2019, around 43% of the MPs had pending criminal cases against them. Therefore, the Court directed that;

- Political parties must publish on their website detailed information regarding pending criminal cases of their candidates (nature of offence, whether charges have been framed, concerned Court, case number, etc.) along with reasons for selection, and also why other candidates without criminal antecedents were not selected. The reasons to be given must be based on qualifications, achievements, and merit of candidate, and not mere ‘winnability’ at the polls.

- The information must be published in a local vernacular newspaper and a national newspaper, and on the official social media platforms of the party including Facebook and Twitter.

- The details should be published within 48 hours of selection of selection of candidate or not less than two weeks before the first date for filing nomination, whichever is earlier.

- The political party must also submit to the ECI, a report of compliance with these directions within 72 hours of selection of candidate in specified formats. Failure of submission of compliance report, the ECI may bring non-compliance by political party to the notice of SC.

From 2002 to 2020, increased transparency about Candidates & their antecedents

To summarize, since 2002, candidates have been obliged to submit the details of the pending criminal records to the ECI. The SC’s judgement in 2018 made it mandatory for these details to be published in the concerned political party website and in newspapers and television channels. This has been further extended to official social media platforms in the 2020 judgement. Furthermore, the 2020 judgement has asked the parties to mention why the candidate with criminal record was chosen in place of those with clean records, apart from their ‘winnability’.

Strict implementation is the need of the hour

Going by the previous experience, political parties are likely to give generalized reasons without much substance, defeating the purpose of these directions. Even with the earlier directions on ‘source of income’, most candidates mentioned generic sources without revealing the actual source of income. Parties & candidates did not even follow the directions regarding publication of pending criminal cases in newspapers and television. Hence these changes would be useful only when there is strict monitoring by the ECI and compliance by all political parties.

The upcoming Bihar elections will be the first general elections to take place after the 2020 judgement of the SC. One will have to wait and see whether or not parties comply with the SC’s order in these elections.