In this edition of court judgements, we look at the Supreme Court’s judgements on medical negligence and termination of an employee for suppression or false information, Kerala High Court’s judgement on the relevancy of previous divorce to permit current marriage, Jammu and Kashmir High Court’s judgement on scope of prevention of corruption act, and Karnataka High Court’s judgement on abetment of suicide.

Supreme Court: In a case where negligence is evident, the principle of res ipsa loquitur operates and the complainant does not have to prove anything as the thing (res) proves itself.

In a significant ruling in CPL Ashish Kumar Chauhan vs. Commanding Officer & Ors., the apex court ruled in favour of an Air Force veteran by awarding Rs. 1.54 crores as compensation and holding the authorities liable for causing medical negligence.

The two-judge bench comprising Justice S Ravindra Bhat and Justice Dipankar Datta was hearing an appeal against the decision of the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC) that earlier dismissed a petition seeking compensation for medical negligence. The appellant’s ordeal began in July 2002 when he fell ill while on duty during “Operation Parakram” in Jammu & Kashmir. He was admitted to 171 Military Hospital, Samba, where he received a blood transfusion as part of his treatment. Fast forward to 2014, and he was diagnosed with HIV. Seeking answers, he requested information about his hospitalization in 2002, which revealed that he had received one unit of blood during his treatment. Subsequent medical evaluations in 2014 and 2015 determined that his disability was indeed related to the blood transfusion he had received in 2002.

In 2016, the appellant was discharged from service without an extension, and he also requested a disability certificate, which was denied, citing a lack of provisions for such a certificate. Frustrated by these developments, he approached NCDRC seeking compensation amounting to Rs. 95 crores. This was dismissed claiming that there was no expert opinion available to establish negligence on the part of the staff at 171 Military Hospital during the blood transfusion.

The appellant argued that the respondent was not able to provide any material evidence such as a blood compatibility report, and hence, did not follow standard operating procedure before any blood transfusion. The respondents argue that the appellant did not provide any proof of medical negligence.

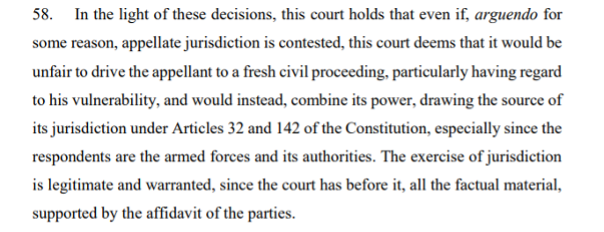

The court looked at whether the current case can be covered by Consumer Protection Act, 1986. The court agreed with the respondents that the Indian Air Force (IAF) and army hospitals did not fall under the ambit of the above act. However, the court looked at an alternate basis for exercising jurisdiction under Articles 32 and 142 of the Constitution.

Further, looking at the material evidence, the court agreed that no alternative option is shown to have been made available to the appellant, when in fact the transfusion did take place. The court referred to Bolam vs. Friern Hospital Management Committee, also known as Bolam Test, which lays down the typical rule for assessing the appropriate standard of reasonable care in negligence cases involving skilled professionals such as doctors. This underlined the duty of doctors to ensure that the patient is aware of any material risks involved in any recommended treatment, and of any reasonable alternative or variant treatments. This was not done in the present case. The court further relied on its earlier judgement in Savita Garg vs. The Director, National Heart Institute, wherein the court had ruled that once the complainant or aggrieved party had adduced some evidence that the patient suffered (or died, as in that case) due to lack of care (or as in this case, suffered irremediable injury due to want of diligence), then the burden lies on the hospital to justify that there was no negligence on the part of the treating doctor or hospital (principle of res ipsa loquitor).

The court decided on compensation based on medical duty care, mental agony to the victim, and future medical care, and awarded Rs. 1.54 crores compensation. It further slammed the authorities for ripping the basic dignity, honour of the appellant and also for lack of compassion towards the appellant. It further remarked that no amount of monetary compensation can undo the harm caused.

Accordingly, the appeal is allowed.

Supreme Court: Employee can be dismissed from their position if it is discovered that they have concealed or provided false information regarding factors that affect their fitness or suitability for the job.

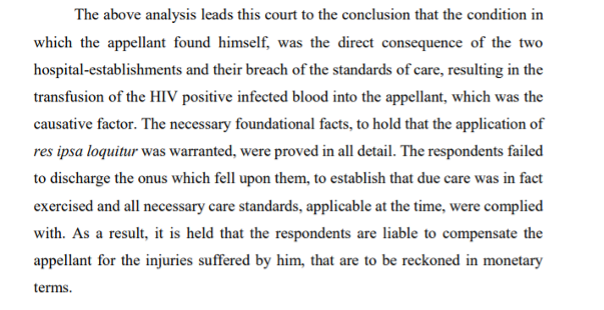

In Satish Chandra Yadav vs. Union of India & Ors, the apex court held that suppression of material information and giving false information in regard to matters which had a bearing on his fitness or suitability for the post, he could be terminated from service during the period of probation without holding any inquiry.

The two-judge bench comprising Justice Surya Kant and Justice J.B. Pardiwala was hearing a special leave petition after the dismissal of the writ petition before the Delhi High Court against the judgement of the division bench that affirmed the dismissal of the appellant herein from service as a Constable (General Duty) with the CRPF.

Brief facts of the case are as follows. The appellant in this case was serving as a Constable (General Duty) with the CRPF. He was hired as a temporary employee for the position of Constable (GD) in the CRPF, post which he reported to the 179th Battalion on 17 December 2015. During his recruitment process with the CRPF, he completed a verification Form–25, wherein he was asked in Column 12 whether there were any pending cases against him. The appellant responded negatively to this question. However, during the Character and Antecedents verification, it was found that the appellant had a criminal case registered against him. On receiving this information, his candidature was terminated in accordance with Rule 5(1) of the Central Civil Services (Temporary Service) Rules, 1965.

The counsel for the appellant argued that the appellant had no knowledge of the pendency of the criminal case on the date when verification was filled, and the suppression cannot be a ground to deny public employment. It relied on Avatar Singh vs. Union of India, where it was held that the circumstances of the case must be looked into while issuing a termination order. The counsel for the respondent vehemently opposed this.

The court relied on multiple judgements and principles of law laid in them as they were inconsistent. Some exercise was done to shortlist broad principles of law.

- Each case should be scrutinised thoroughly by the public employer concerned, through its designated officials.

- The acquittal in a criminal case would not automatically entitle a candidate for appointment to the post. It would be still open to the employer to consider the antecedents and examine whether the candidate concerned is suitable and fit for appointment to the post.

- The suppression of material information and making a false statement in the verification Form relating to arrest, prosecution, conviction etc., has a clear bearing on the character, conduct and antecedents of the employee.

- The generalisations about the youth, career prospects and age of the candidates should not enter the judicial verdict.

Based on these principles, the court did not agree with the appellant’s case.

The court concluded that it was a deliberate attempt on the part of the appellant to withhold the relevant information and it is this omission which has led to the termination of his service during the probation period. Accordingly, the appeal is dismissed.

Kerala HC: Nature of previous divorce is irrelevant, only essential aspect is that the couple do not have living spouses at the time of marriage registration.

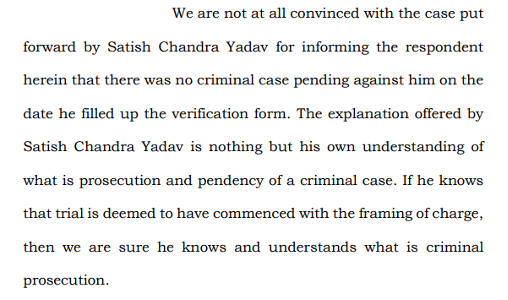

The Kerala High Court, in Antony Joseph vs. The Sub-Registrar, held that the only essential aspect during registration of a marriage is that both the parties do not have any living spouse at that time, and the nature of previous divorces is not relevant, under the Special Marriage Act, 1954.

The Single-judge bench comprising Justice Devan Ramachandran was hearing a petition against the order of the registering authority that rejected the marriage on the grounds that there was no sufficient evidence to show that both parties were single or without any living spouse at that time. The registering authority issued an order that unless both parties show that their respective divorces were obtained on mutual consent, it cannot be acted upon. This petition is against such an order.

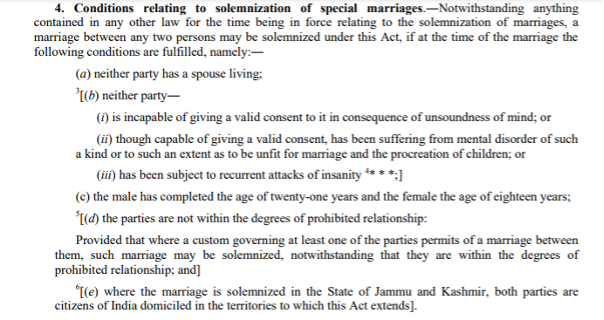

Section 4 of the act deals with the conditions relating to the solemnization of special marriages.

The court looked at the orders obtained by both parties from Authorities/Courts in the United Kingdom, indicating that both of them have obtained divorces from their respective earlier spouses. The court further looked at sections 4, 7, and 8 of the Special Marriage Act, and remarked that it only requires the parties to satisfy the Registering Authority that they have no living spouses at the time when the application is made and the marriage is registered. It further remarked that no law mandates that all divorces are obtained by ‘mutual consent’.

Accordingly, the earlier order is set aside, and the respondent is directed to reconsider the application by examining the material facts and if he is satisfied, the request for marriage should be acceded to, if there is compliance with other requirements of the law.

Jammu and Kashmir HC: Offences under Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 not limited to just public servants, but can be invoked against people discharging public duty.

In Sheikh Abdul Majeed vs. UT Of J&K, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court held that The proliferation of novel ways of indulging in corrupt practices is alarming and has prompted the courts to widen the scope of interpretation of the words “public servant” in line with the objective of the Act. Accordingly, people discharging ‘public duty’ can also be included under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. hereby referred to as act.

The Single judge bench comprising Justice Wasim Sadiq Nargal was hearing a petition seeking the quashing of an FIR registered under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. The brief facts of the case are as follows. The petitioner constructed a godown on his proprietary land and leased it out to the Food Corporation of India (FCI). A truck driver filed a complaint, claiming that he was demanded a bribe by the owner of the godown and a person responsible for weighing goods to unload the food grains from his truck. Subsequently, an FIR was lodged by the Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) in Srinagar, invoking Sections 7 and 7A of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, in response to this allegation.

The petitioners argued that the FIR was not tenable as the present case did not involve any ‘Public Servants’, and that ACB overreached its jurisdiction, thereby depriving the liberty of petitioners. The respondents argued that Section 2 (c) (viii) of the PC Act envisages a public servant to include, “any person who holds an office by virtue of which he is authorized or required to perform any public duty”. Here, the nature of duty is important and not the position held.

Looking at the arguments, the court examined two questions of law.

To answer the first question, the court looked at the statutory provisions of the act, and also the objects and reasons of the enactment of the act. The court remarked that it would be inappropriate to limit the definition clause that would be against the spirit of the act itself. In State of Gujarat vs. Mansukhbhai Kanjibhai Shah, the apex court held that the purpose under the PC Act was to shift focus from those who are traditionally called public officials, to those individuals who perform public duties.

Accordingly, the Court held that the petitioner performs ‘public duties’ and is liable to be tried under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. Further, the court remarked that if the allegations in the FIR are taken at face value, prima facie reveals that the ingredients of Sections 7 and 7A are fulfilled and the petitioners, who have been held to be public servant performing public duty, can be proceeded in terms of the said of the Act.

Accordingly, the petition is dismissed.

Karnataka HC: Insisting to repay the borrowed money does not amount to abetment of suicide under section 306 of IPC.

In Mangala Gowri vs. State of Karnataka, the Karnataka High Court held that merely insisting on repayment of borrowed loan does not amount to abetment of suicide under section 306 of the Indian Penal Code unless there be such an action on the part of the accused which compels the person to commit suicide; and such an offending action ought to be proximate to the time of occurrence.

The Single judge bench of Justice Shivashankar Amarannavar was hearing an appeal against the judgment of Additional District Sessions Court that convicted the appellant for abetment of suicide. The deceased borrowed money from the appellant and was allegedly harassed for repayment. However, the appellant argued that the mere demand of repayment of borrowed money does not amount to abetment of suicide.

The court looked at the facts of the case and heard both sides. The court relied on multiple judgements of apex court, including M.Mohan vs. State, wherein it was held that there has to be a clear mens rea to commit the offence.

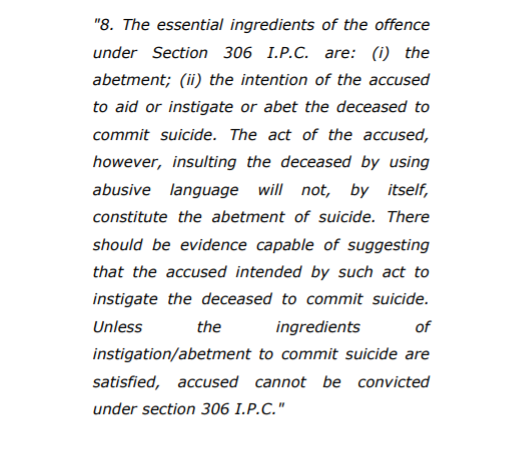

The court further looked at M.Arjunan vs. State, where the apex court held that The key elements of the offense defined in Section 306 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) are as follows: (i) involvement in abetment, and (ii) the intention of the accused to assist, provoke, or abet the deceased in committing suicide. It is important to note that merely insulting the deceased through the use of offensive language by the accused does not, on its own, qualify as an act of abetment to suicide.

The court remarked that the current case does not look like abetment from any angle. Accordingly, the impugned order is set aside, and the appeal is allowed.