Since 13 February 2024, numerous farm unions in India have been engaged in a strike, advocating for a legislation on floor pricing, also known as the minimum support price, for their agricultural produce. In this story, we look at the trends in the production and procurement of food grains and look at some of the underlying issues in farming.

Since 13 February 2024, numerous farm unions in India have been engaged in a strike, advocating for legislation on floor pricing, also known as the minimum support price, for their agricultural produce. The ongoing protests involve tens of thousands of Indian farmers reviving a movement that successfully led to the repeal of contentious agricultural laws in 2021. Two years after concluding a large-scale protest, Indian farmers have returned to the streets, emphasizing the necessity of guaranteed prices for their crops. Farmers assert that their primary demand, the enactment of minimum support price legislation, would ensure sustainable rates for their crops, providing them with fair earnings.

Over 60% of India’s population relies primarily on agriculture for their livelihoods, despite the sector contributing less than 20% to the nation’s economic output. Persistent issues such as debts and bankruptcy have driven farmers to alarming rates of suicide. There is a consensus that India’s previous system, which encouraged farmers to produce an excessive surplus of grains, requires rectification. However, the means and methods of such rectifications are complex, with no easy answers. Unfortunately, more attention is being laid on farmers and protests rather than the core underlying issues.

In this story, we look at the trends in the production and procurement of food grains and look at some of the underlying issues in farming.

MSP over the years- Wheat and Paddy among the least gainers

Since the “Green Revolution” in the 1960s, the Indian government has operated a program guaranteeing farmers a fixed price for specific crops. Coupled with advancements in farming technology, this system has played a crucial role in transforming India from widespread hunger to consistently achieving substantial annual food surpluses. The Government of India announces the Minimum Support Prices (MSP) as per the recommendation of the Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), before every harvest (Rabi/kharif season).

The data on MSPs since the marketing year 2010-11 show that over the past 14 years, the MSPs of crops have grown with varying growth rates. Crops such as Ragi and Jowar registered over 200% growth, while crops such as Bajra, Maize, Barley, and Paddy registered over 100% growth. Wheat is the crop that registered the least growth, with only a 93% rise during the same period.

In terms of CAGR, MSP for Ragi grew at 10.4%, followed by Jowar at 9.5%, Maize at 6.4%, Barley at 6.2%, Paddy at 5.6%, and wheat at 4.8%.

Rice and Wheat production up by 30%, while Jowar and Ragi register decline in production.

In terms of production among the major food grains, between 2014-15 and 2022-23, it is observed that Rice production grew from 105.5 million Tonnes to 135.8 million Tonnes, marking a 29% rise. During the similar period, Wheat production grew from 85.6 million Tonnes to 110.6 million Tonnes, showing a 28% rise. Similarly, Maize production rose from 24.2 million Tonnes to 38 million Tonnes, rising by almost 60%.

However, Jowar production declined from 5.5 million tonnes to 3.8 million tonnes, marking a 30% decline. Similarly, Ragi production too declined from 2.1 million tonnes to 1.7 million tonnes, marking an 18% decline.

Procurement of rice and wheat see decline in last two years.

The procurement of food grains is a crucial element in achieving the goal of making food grains available to the poorer sections at reasonable prices and guaranteeing a Minimum Support Price (MSP) to the farmers. This process plays a vital role in effective market intervention, controlling prices, and contributing to the broader food security of the nation. The Food Corporation of India (FCI), as the primary central agency of the Government of India, collaborates with various state agencies to carry out the procurement of wheat and paddy.

The data on procurements show that procurement of rice and wheat has fallen in the last two years. During the marketing year 2011-12, the procurement of rice stood at 35.1 million Tonnes, rising to a highest of 60.2 million tonnes during the COVID-19 pandemic period from 2020-21. However, the procurement fell in the following two consecutive marketing years. Similarly, the procurement of wheat was at 28.3 million tonnes in 2011-12, rising to a highest of 43.3 million tonnes in 2021-22. Post 2021-22, the procurement of wheat declined by more than half.

Procurement distribution is uneven, concentrated in few states.

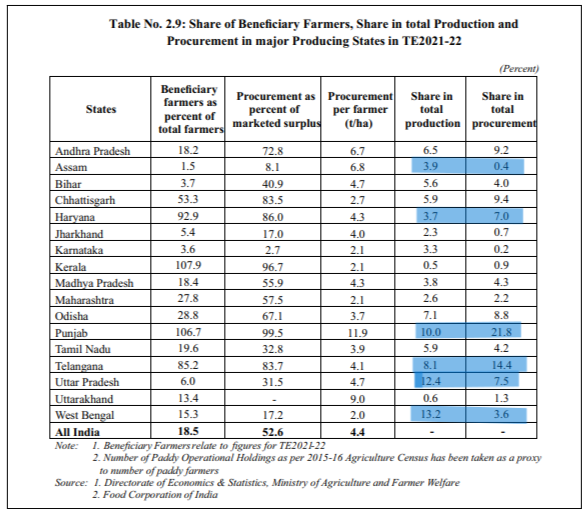

The state-level data on procurement of paddy show that procurement operations remain concentrated in a handful of states, lacking equity among various rice-producing states nationwide. In TE 2021-22, West Bengal accounted for 13.2% of the total rice production, however, its procurement share is only 3.6%. Similar is the case with Uttar Pradesh, which accounts for 12.4% of rice production, but the share in procurement is 7.5%. In contrast, Punjab accounts for 10% of rice production, but 22% of procurement out of total procurement. Similarly, Telangana accounts for 8.1% of production, but 14.4% of the procurement.

Significant disparities in average procurement per farmer are also apparent, with procurement per farmer ranging from 11.9 tonnes in Punjab and 9 tonnes in Uttarakhand to less than 3 tonnes in Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Kerala, and West Bengal.

These uneven distributions raise concerns about social equity and efficiency.

Terms of trade remain low indicating unfavourable exchange conditions for farmers.

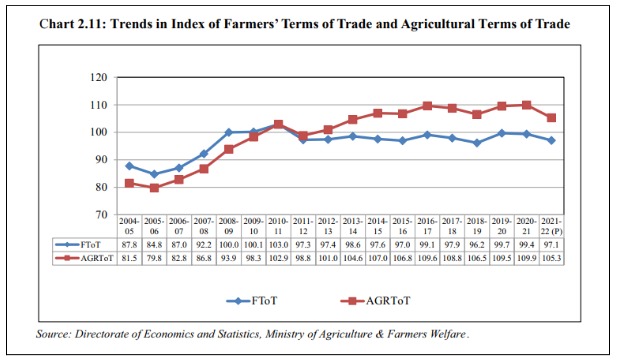

The CACP considers the Terms of Trade (ToT) between the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors as a factor in determining the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for mandated crops. Terms of Trade (ToT) for farmers are calculated as the ratio of the Index of Prices Received (IPR) to the Index of Prices Paid (IPP). A ToT ratio exceeding one (or 100%) signifies favourable pricing power for farmers, indicating that they receive higher prices for their products compared to the prices they pay for inputs. Conversely, a ToT ratio below one indicates unfavourable conditions of exchange, suggesting that farmers receive lower prices for their products relative to the costs of their inputs.

The Farmers’ Terms of Trade index exhibited an increase from 87.8 in 2004-05 to 103 in 2010-11. However, from 2011-12 onward, the index remained slightly below 100 and was recorded at 97.1 in the fiscal year 2021-22(P). Excepting the three years between 2008-09 to 2010-11, the ToT ratio recorded below 100%, indicating the unfavourable pricing power for farmers.

Market prices well below the MSP of Paddy

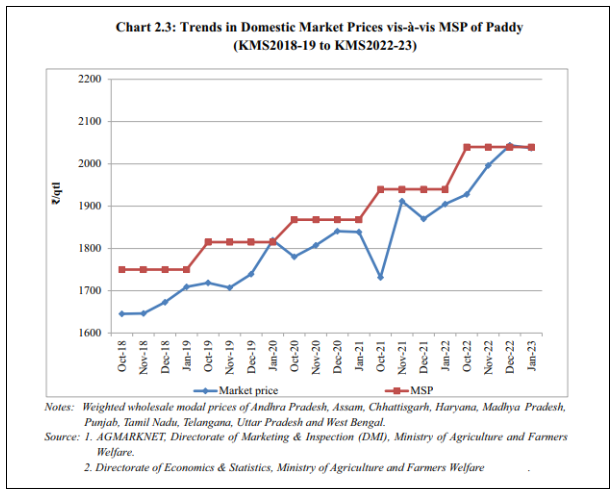

One of the key issues of the farmer protests is the legislation for MSP. Farmers have the discretion to sell their produce anywhere- either to private players or the government procurement agencies, wherever they get better prices. Data on market prices has been gathered from 3,100 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMC) mandis across various States and Union Territories (UTs) through AGMARKNET for analysis purposes. Market price denotes the rate at which farmers sell their crops at these mandis. The state-weighted average daily price of a commodity has been calculated by averaging the modal price observed at different centres, with the daily market arrivals at each centre serving as the weights for computation.

The trends in domestic market prices compared to the Minimum Support Price (MSP) of paddy for the Kharif Marketing Season (KMS) from 2018-19 to 2022-23 show that the market prices of paddy remained below the MSP. However, during the KMS of 2022-23, although the market prices were still below the MSP, they displayed a rising trajectory. Towards the conclusion of the KMS of 2022-23, market prices approached closely with the MSP.

Market prices below MSP are almost the case with other crops, except soyabean and cotton. In such scenarios, government procurement at MSP is a better economic alternative for farmers.

MSP provides a margin over the cost of production.

When market prices fall due to various factors, the government’s MSP comes as a support, providing a cushion against distortions. The MSP is recommended by the CACP and is calculated keeping in mind the supply and demand, cost of production, and inter-crop price parity among other factors. The government establishes the Minimum Support Price (MSP) at 1.5 times the Cost of Production (CoP), where CoP is calculated as A2+FL. However, the Swaminathan Commission recommends that the CoP should be determined based on C2, advocating for the ‘C2+50 per cent’ formula for setting MSP. One of the major demands of the farmers is to implement the recommendations of the Swaminathan Commission.

Here, A2 means the Paid-out cost or cultivation expenses, covering inputs like seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, hired labour, fuel, and irrigation, incurred by farmers. A2+FL is the Paid-out cost-plus imputed value of family labour and C2 is the Paid out cost-plus imputed value of family labour plus rental value of owned land and interest on fixed capital.

The data on margin in MSP over the cost of production considering C2 show for Paddy, the average margin hovers around 12%, while for Jowar it is around 10% only. Except for Bajra, all other crops have a margin of less than 20%. While the government has guaranteed a margin of a minimum of 50% above A2+FL, the margins when compared to C2 are way below 20%.

Several media reports suggest that the actual cost of production computed by the respective state agricultural commissions is more than the cost of production calculated by CACP. As a result, even if MSP is assured, farmers will incur losses.

Comprehensive reforms needed to overcome ‘Triple challenge’.

The above charts show the economic vulnerability of the farmers, despite the assurance of a minimum support price. In fact, only a small percentage of farmers benefit from MSP, while the rest succumb to market volatility. Furthermore, a report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests that the convergence of domestic and trade policies has led to a reduction in Indian farm revenue by approximately 5.7% over the past three years, translating to Rs. 1.7 trillion per year of ‘implicit taxation’.

The report also notes that, like other countries, India also faces the ‘Triple Challenge’ – Providing safe and nutritious food to an expanding population at reasonable prices, sustaining livelihoods for farmers and individuals in the food supply chain, and addressing significant resource and climate challenges. Overcoming this triple challenge requires action on multiple domains and at multiple levels, from trade policies to domestic policies, from infrastructure development to improvement in agricultural institutions, from union governments to federal governments and so on.