The NCRB data indicates that though the number of new ‘riot’ cases has come down in the last few years, the pendency with the police has increased. Data further indicates that the same is the case with the courts. The annual disposal rate in courts of ‘riot’ cases is a dismal less than 10%. Even in those, more people are acquitted than convicted.

In the earlier story, we analysed the trends in Police disposal of cases relating to offences against Public tranquillity. The data indicates that even though the number of reported cases has come down, the pendency rate with the police has increased.

We have also observed that around 70% of the cases that are being investigated by the police are being chargesheeted within a period of 6 months and then move to the courts for trial. Trends over the last three years indicate that the number of cases being chargesheeted by police has reduced in line with the fall in the number of reported cases, although the charge sheeting rate has gone up. Even the proportion of long-standing cases being chargesheeted has increased in the recent times.

Like we discussed in the previous story, the complete picture of the quality of the police investigation would be clear only after looking at the court disposal of these cases. In this story, we look at the numbers provided in NCRB’s Crime in India reports regarding disposal of these cases in courts.

Like with Police, pendency has increased in Courts despite a fall in new cases

Numbers from the last two years i.e. 2018 & 2019 indicate that the number of cases sent for trial at the courts has reduced. After an increase in 2017, the number of new cases sent for trial has shown a downward trend. In spite of a reduced number of cases that came up for trial, the total number of cases pending in courts at the end of each year has seen a consistent increase. In 2015, more than 4.95 lakh cases relating to ‘offences against public tranquillity’ were up for trial in courts, which increased to 5.71 lakh cases in 2019.

Further, the number of cases pending trial in courts at the end of a year also saw a year-on-year increase despite the reduction in the number of new cases. Over the five-year period (2015-19), the number of cases pending trial in the courts at the end of the year increased from more than 4.57 lakh cases by the end of 2015 to 5.33 lakh cases by the end of 2019.

With this huge backlog of cases pending trial in the courts, no amount of reduction in the new cases would help unless there is a substantial improvement of 3-4 times in the disposal rate. Only such an increase in the disposal rate would be able to reduce the pendency in courts.

Number of Acquittals are higher than convictions, however the ratio has reduced

Data indicates that in 2018 & 2019, the number of cases disposed by the courts is less than the number compared to that of 2017. Compared to 37.8 thousand trials completed in 2017, the various courts in India were only able to complete trials of 35.9 thousand and 35.3 thousand cases relating to offences against public tranquillity in 2018 and 2019. However, these numbers are slightly higher than 2015 and 2016.

Apart from the cases which resulted in an acquittal or a conviction, a sizable number of cases are disposed without conducting a trial. These could be because of the prosecution (governments) withdrawing cases. The number of such cases also fell over the period 2015-19.

Data indicates that in the cases relating to ‘Offences against Public Tranquillity’, the number of acquittals is significantly more than the convictions. However, the ratio of Acquittals and Convictions has come down over the years. In 2015, there were more than 4 acquittals for every conviction, which has come down to around 2.3 in 2019. This is due to an increase in the number of convictions and a reduction in the number of acquittals over the years. The trend of acquittals being more than convictions is contrary to the overall trend in IPC cases where the number of convictions is higher than the acquittals.

Number of Acquittals compared to Convictions is higher in ‘Riot’ cases

Cases belonging to ‘Rioting’ form the major portion of the cases up for trials in the courts for ‘Offences Against Public Tranquillity’. Around 4.7 of the 5.7 lakh cases i.e. 83% of the cases of ‘offences against public tranquillity’ that are pending trial in the courts at the end of 2019 are related to ‘rioting’. The proportion of these cases was much higher in 2017 when 91% of the pending cases under this head belonged to riots.

Meanwhile, in terms of disposal of these ‘riot’ cases, the numbers have reduced in line with the overall trend. However, the major variation is in the ratio of Convictions to Acquittals.

For all ‘offences against pubic tranquillity’, the ratio of acquittals to convictions has reduced over the years while the ratio remained nearly the same in the case of ‘riots’.

Around 75% of the cases in court pending trial for more than a year

Out of the 5.33 lakh cases relating to ‘offences against Public Tranquillity’ that were pending in courts by the end of 2019, 3.25 lakh cases were pending for a period of 1-5 years, and another 79 thousand cases were pending for more than 5 years. Together, these make up for 75% of the cases under the category ‘offences against Public Tranquillity’ that were pending in courts at the end of 2019. The proportion of cases that were pending for more than a year, was nearly the same even in earlier years.

There was a significant drop in the long-standing cases, i.e. pending for over 10 years. In 2017, there were around 21 thousand such cases which reduced to around 15 thousand in 2019.

This fall in the long pending cases can be attributed to the disposal of long standing ‘riot’ cases. In 2017, there were 19.8 thousand ‘riot’ cases that were pending for more than 10 years. By end of 2018, this fell to 15.2 thousand and by the end of 2019, there were around 13.7 thousand ‘riot’ cases pending for over 10 years.

Reasons for delay include challenges with police investigation, rules & procedures of court etc.

Pendency of cases in courts is an issue not limited to these offences. We had analysed the pendency in courts earlier. One of the key observations was that a majority of the cases that are pending in the courts are at the stages of ‘Collection of Evidence’ and ‘Appearance in Courts’.

The data in this story, points to a huge backlog of cases that are pending, especially the ‘riot’ cases. The annual disposal rate is less than 10% in these cases.

While there aren’t any conclusive studies which establish the reasons for such a delay in disposal of these cases by police and courts, few other studies and reports relating to specific incidents shed some light.

A report published by Human Rights Watch about the 1984 Sikh Riots point out to the Complicity and Dereliction of duty by public officials especially the police. It highlights that after more than 3 decades, only around 30 persons have been convicted in respect to the riots which took place at such a large scale. The authorities involved are accused of repeatedly blocking the investigations and protecting the perpetrators. Poor investigation has contributed at large towards acquittals. Because of long duration of these trials, many of the victims, accused and witnesses had died in between further complicating the trial process.

This report to an extent supports the data where in the number of acquittals is higher than the convictions.

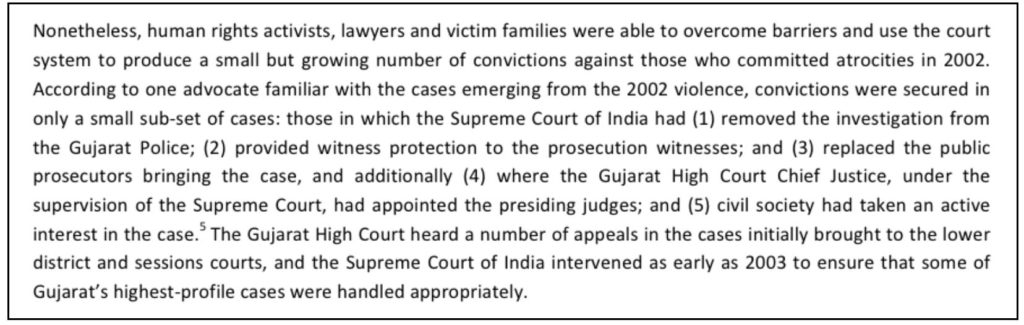

A Study by Stanford Law School on 2002 Gujarat Riots titled ‘When Justice Becomes the Victim: The Quest for Justice After the 2002 Violence in Gujarat’, bemoans the fact that the conviction rate in these ‘riot’ cases was only 1.2% as against the national average of 18.5% for all riot related cases. It notes that the convictions even to this extent were possible only after – the investigation was taken away from Gujarat police, witness protection was provided, change in public prosecutors etc.

These reasons summarise the challenges in providing justice in ‘riot’ related cases in such large-scale riots and concurs with the reasons mentioned in the report related to ‘Anti-Sikh’ riots.

While these are some of the ground realities observed for two of the large-scale riots, challenges stemming from judicial procedures also contribute towards court delays.

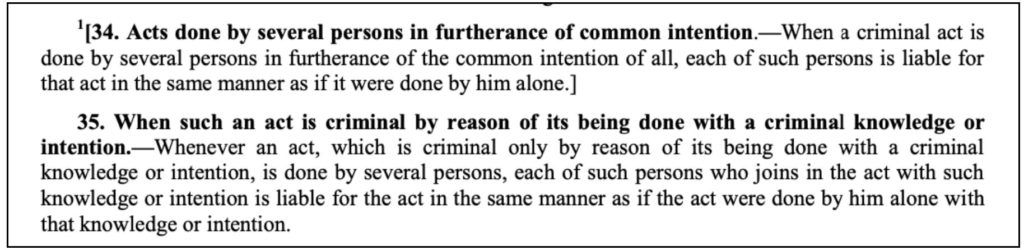

Section 34 and 35 of Indian Penal Code, discuss the concept of common intention in performing a criminal act.

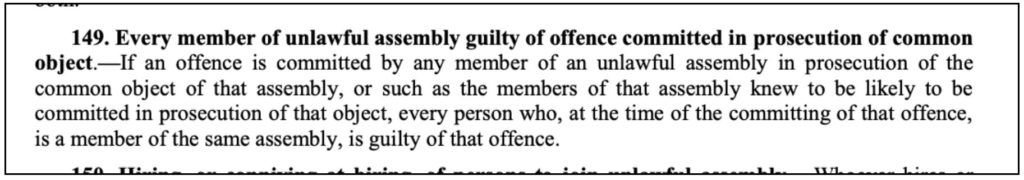

Section 149 of IPC more specifically states the law regarding Unlawful assembly.

In all these sections, the law clearly states that any member who is part of the unlawful assembly with a common intention and common object is guilty. However, in most cases, it is difficult for the investigating authorities to ascertain who is part of the unlawful assembly and is involved with an intent and vice versa. Obtaining evidence for the same is always a challenge which either leads to eventual acquittal or pendency. Examples involving high profile individuals (e.g. Anti-Sikh Riots -1984, Gujarat Riots -2002, Delhi Riots -2020 etc.) show that they are acquitted or not charged due to the lack of prosecutable evidence that links them to the riots. In other cases, involving common people, this ambiguity leads to longer delays. The traditional problems with police investigation also contribute the higher acquittals.

The Rules & Orders issued by Punjab High Court regarding Trial of Riot Cases, provides an insight into the handling of these cases. The rules also highlight exemplify the challenges in handling these cases. Few of these include :

- Danger of innocent persons being implicated along with the guilty, with tendency of the parties in such cases to try to implicate falsely as many of their enemies as they can.

- Involved parties generally give widely divergent versions of the riot

- The question of who the aggressor is and who is acting in self-defence

- When both parties to a riot are prosecuted, two cases must be tried separately and evidence in the one case cannot be treated as evidence in the other

- In recording evidence in riot cases, care should be taken to bring out distinctly as far as possible the connection of each of the accused with the crime and the actual part played

- When a number of offences are committed by members of an unlawful assembly in the course of the riot in prosecution of their common object, each member is guilty not only of rioting but of every other offence committed by himself or by the other members of the unlawful assembly

All this means that the complexities involved in collecting evidence along with the complicit nature of the authorities not only delays the trials in the courts, but also ensures that more accused are acquitted than convicted.

Featured Image: Annual Court disposal rate