In this edition of Court Judgements, we look at the Supreme Court’s interim decision on petition to disclose Form 17C Records of votes polled, punishment for casteist insults under SC/ST Act, Bombay High Court’s judgement on Leave Encashment, Patna High Court decision on ambit of ‘Dowry’ and the Himachal Pradesh High Court’s judgement on whether speaker can be directed to act upon within a fixed time frame.

Supreme Court: Hands-off approach during elections, cannot interfere in the ongoing electoral process.

In Association for Democratic Reforms vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court had declined to interfere in the electoral process by refusing to direct the Election Commission of India (ECI) to publish the booth-wise absolute number of votes polled and also to upload the Form 17C on its website.

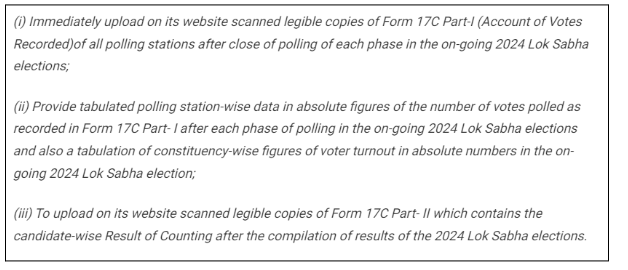

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) has filed an interlocutory application to the Supreme Court, requesting that the Election Commission of India (ECI) promptly publish the exact numbers of polled votes. It is alleged that there is a significant time delay (first phase- 11 days and second phase- 4 days) in publishing the voter turnout data, and also a discrepancy of 5% between initial and final voting figures. It is argued that such unreasonable delays along with discrepancies have created apprehensions among voters. This application has been filed as an Interlocutory Application in a writ petition originally submitted by ADR in 2019, which alleged discrepancies in voter turnout data for the 2019 General Elections. The application sought three directions to the ECI by the apex court.

Opposing the application filed by ADR, the Election Commission (ECI) informed the Supreme Court that releasing Form 17C data indiscriminately could lead to the manipulation of images, including vote counts, thereby creating public discomfort and mistrust in the electoral process. The ECI also clarified that, according to the rules, Form 17C is to be provided only to polling agents, and not to any other entity. General public disclosure of Form 17C is not permitted by the rules. Further, the ECI also argued that any perceived delay or difference in voter turnout percentages is within the expected range given the process’s scale and magnitude.

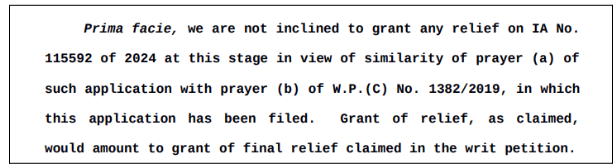

After hearing arguments from both parties, the Apex Court expressed its reluctance to interfere in the ongoing election process.

Interestingly, the Election Commission of India published the absolute number of voters for all completed phases on 25 May 2024, a day after this decision.

Accordingly, the petition is scheduled for re-listing on another day.

Supreme Court: Casteist insults must be made in a place within public view to attract provisions under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

The Supreme Court, in Priti Agarwalla and Others vs. The State of GNCT of Delhi and Others, held that for an offence to be decided under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, the allegation of insult must meet the requirement of having been made in a place within public view.

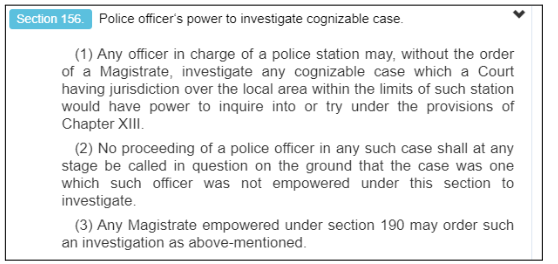

The two-judge bench comprising Justice M.M Sundresh and Justice S.V.N. Bhatti was hearing a petition filed by the appellant. In this case, the appellant claimed that an offence under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, had been committed against him. However, the victim claims that no action was not taken up, inquired, or investigated by the SHO of P.S. Fatehpur Beri on his complaint. Based on this, he filed an application under Section 156 of the CrPC with the Trial Court, seeking an order to register an FIR.

The Court subsequently ordered a preliminary inquiry into the matter and, after review, dismissed the application. The appellant challenged this dismissal by filing an appeal with the High Court, that directed the registration of FIR. It is against this decision the appeal is filed with the apex court.

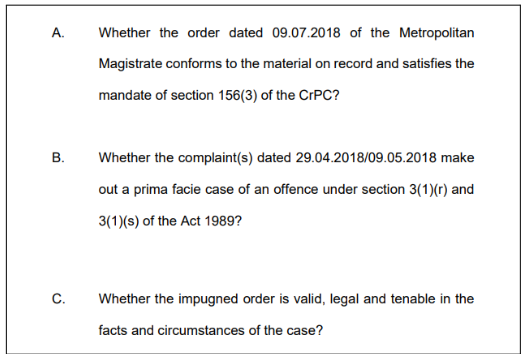

After hearing both parties, the court listed the issues for consideration.

On the A & C questions, the court stated that it is well-established and self-evident from decisions under Section 156(3) of the CrPC that a Magistrate exercises discretion judiciously, considering the circumstances and the alleged offence before taking any action. The court further believes that the Metropolitan Magistrate acted appropriately and without any illegality or irregularity in seeking a preliminary inquiry or receiving the Action Taken Report from the relevant police station.

However, for an FIR to be registered, the complaint should satisfy the essential ingredients of the offences alleged. If such allegations in the petition are vague and do not specify the alleged offences, it cannot lead to an order for the registration of an FIR and investigation.

The court highlighted that sections 3(1)(r) and 3(1)(s) cumulatively state that the insult or abuse must be intentional, coupled with the humiliation made in any place within public view.

In Pramod Suryabhan Pawar vs. State of Maharashtra, it was held that messages sent on WhatsApp could not be said to be an act of intentional insult or intimidation or an intent to humiliate in a public place within public view.

Accordingly, the decision of the High Court directing the registration of an FIR was held untenable. The Criminal Appeal was allowed, and the order of the Metropolitan Magistrate was upheld.

Bombay HC: Leave encashment is akin to salary, depriving it with any valid statutory provision would violate Article 300A of the Indian Constitution.

In Dattaram Atmaram Sawant vs. Vidarbha Konkan Gramin Bank, the Bombay High Court held that leave encashment is recognized as a right by courts, and can only be restricted by another statutory provision backing it.

The two-judge bench comprising Justice Nitin Jamdar and Justice M.M. Sathaye was hearing a petition to decide whether the petitioners lost the right to encash their privileged leave since they resigned. The brief facts of the case are as follows. Dattaram Sawant joined the bank as an Assistant Manager on 8 December 1984, serving for over 30 years until his resignation on 2 August 2015. Seema Sawant began her tenure as a Cashier on 6 August 1984 and resigned on 1 October 2014. Although both completed the resignation formalities and received experience certificates confirming satisfactory service, the bank denied their requests for leave encashment. Significant changes in the bank’s service regulations occurred following the amalgamation of Wainganga Krishna Gramin Bank with Vidarbha Konkan Gramin Bank. The revised regulations, effective from 28 October 2013, under Vidarbha Konkan Gramin Bank (Officers and Employees) Service Regulations, 2013, included provisions for privilege leave, calculated at one day for every 11 days of service, and allowed accumulation of up to 240 days post-1989.

The counsel for the bank argued that only those who resigned after 14 September 2015 are entitled to leave encashment as the facility for encashment of privilege leave came into existence on that date. Since the petitioners resigned before, they were not eligible. The key question before the court is whether resignation would take away the right to claim leave encashment.

Upon looking at the various judgements by the petitioners where the right of earned leave encashment had been upheld, the High Court agreed with the contentions of the petitioners. The court held that leave encashment is like a salary, which constitutes property. Depriving a person of their property without any valid statutory provision would violate Article 300A of the Constitution of India.

Further, the court relied on the judgement in The Karnataka Vikas Grameena Bank, Dharwad-8 and another vs. Chandrasekhar, where it was held that there is no distinction between the one who retired and resigned since the benefits have already been accrued.

Accordingly, the High Court ruled in favour of the petitioners, affirming their entitlement to the encashment of privilege leave and directed the Vidarbha Konkan Gramin Bank to pay the amounts owed for leave encashment, along with interest at a rate of 6% per annum to the petitioners.

Patna HC: Demanding money from paternal home for the maintenance of newborn baby does not come within the definition of ‘dowry’.

The Patna High Court, in Naresh Pandit vs. The State of Bihar and another, held that if a husband demands money from his wife’s paternal home for the rearing and maintenance of their newborn child, such a demand does not fall under the definition of ‘dowry’ as per Section 2(i) of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961.

The single judge bench of Justice Bibek Chaudhuri was hearing a revision petition challenging the order of conviction passed by the Additional Sessions Judge-III for offence under section 498A of IPC and section 4 of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. The brief facts of the case are as follows. The couple’s marriage was solemnized according to Hindu rituals in 1994. They subsequently lived together as spouses, and during their union, they had three children: two sons and one daughter, with the daughter being born around 2001. The wife alleged that three years after their daughter’s birth, the petitioner and his relatives demanded Rs. 10,000 from her father to support and care for the girl child. It is also alleged that she was subjected to torture due to the non-fulfilment of the petitioner’s demand and that of his relatives.

Upon hearing both parties, the court highlighted the issue for consideration in the appeal.

The Court relied on the apex court judgements in Bachni Devi & Anr. Vs. State of Haryana and Satvir Singh & Others vs. State of Punjab and Another,. In Bachni Devi case, the apex court held that the definition of the expression ‘dowry’ as contained in Section 2 of the Act cannot be restricted solely to the ‘demand’ of money, property, or valuable security made at or after the performance of marriage. The legislature, in its wisdom, while defining ‘dowry,’ has emphasized that any money, property, or valuable security given as consideration for marriage, “before, at, or after” the marriage, would be covered by the expression ‘dowry.’ This definition, as contained in Section 2, must be applied wherever the expression ‘dowry’ appears in the Act.

Thus, any ‘demand’ of money, property, or valuable security made from the bride or her parents or other relatives by the bridegroom or his parents or other relatives, or vice versa, would fall within the scope of ‘dowry’ under the Act if such demand is not properly referable to any legally recognized claim and is solely related to the consideration of marriage.

This was further reiterated in Satvir Singh case, where it was held that giving or agreeing to give any property or valuable security on any of the above three stages should have been in connection with the marriage of the parties.

The court had held that the demand of money for the maintenance of a girl child does not come under ‘dowry’ and since cruelty is read with section 2(i) of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, the charge of 498A of IPC is not established against the petitioner. Accordingly, after examining the material on record, the conviction passed by the lower court was set aside.

Himachal Pradesh HC: Split verdict on whether speaker can be directed to decide on resignation letters of legislators within a specific time frame.

The Himachal Pradesh High Court, in Hoshyar Singh Chambyal and others vs. Hon’ble Speaker, H.P. Legislative Assembly and others, delivered a split verdict on whether the court can utilize its powers under Article 226 of the Constitution of India to instruct the speaker of the house to decide on resignation letters submitted by a member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) within a specific time frame.

The two-judge bench comprising Chief Justice MS Ramachandra Rao and Justice Jyotsna Rewak Dua delivered the split verdict, with the Chief Justice declining to issue any such instructions for the speaker whereas Justice Jyotsna disagreed with the CJ and directed the speaker to decide on the resignations within two weeks. The brief facts of the case are as follows: Independent members of the legislature submitted their resignations and joined the BJP. However, their resignations were not decided by the speaker.

The counsel for the petitioners argued that their resignations were voluntary and genuine, as they personally handed them to the Speaker. They argued that any doubts about the voluntariness of their resignations were fabricated to impede their right to resign from the Assembly. However, counsel for the respondent argued that the power to accept resignations is vested exclusively in the Speaker’s office and is not subject to judicial review. It is further asserted that the Speaker’s role is distinct from that of an ordinary executive authority, thus exempting him from judicial interference.

Upon hearing both parties, the bench delivered a split verdict. The Chief Justice expressed reluctance to issue directions to the speaker. The Chief Justice relied on several judgements, including Subash Desai vs. Principal Secretary, Governor of Maharashtra, whereby it was decided that judicial review is not available at a stage before the decision of the Speaker or Chairman, except in certain exceptional circumstances detailed in that case. Further, a similar petition is pending before the Chief Justice of India to constitute a Bench to decide the said issue. However, since no authoritative decision on the issue has been given by the Supreme Court, such relief is not permissible.

In contrast, Justice Jyostna held that the Speaker has the right to conduct an inquiry and has the discretion to accept or reject the resignations. However, the inquiry cannot be overly broad. In any given case, the inquiry should be conducted solely to determine whether the resignations tendered by the Members of the Legislative Assembly were voluntary and genuine, and nothing beyond that. There cannot be a roving inquiry. The power to provide relief is always available to the Court that possesses the authority to issue high prerogative writs. Further, it is stated that Constitutional Authority has to act and conduct following the Constitution, which is supreme.

Accordingly, Justice Jyotsna directed the speaker to decide on the resignations within two weeks from the date on which this judgement was intimated to him.

Since the verdict is contrasting, the matter would be listed before the Chief Justice for further action.