In this edition of Court Judgements, we look at the Supreme Court’s judgement on power of states to tax mineral rights and fiscal federalism, Kerala High Court’s judgement on compromise of sexual crime, and conflict between Child Marriage Act and Muslim Personal Law, Andhra Pradesh High Court’s judgement on depositing passport, and Calcutta High Court’s judgement on section 354A of IPC.

Supreme Court: Fiscal federalism in accordance with constitutional limits must be safeguarded from unconstitutional interference by Parliament.

In a significant judgment, Mineral Area Development vs. M/S Steel Authority Of India & Ors, the Constitution Bench of the apex court, by an 8:1 majority, ruled that taxation is a vital source of revenue for the States and their power to levy taxes within their legislative domain, as defined by the Constitution, must be protected from unconstitutional interference by Parliament, while upholding the States’ power to tax mineral rights and mineral-bearing lands.

The present appeals address the distribution of legislative powers between the Union and the States regarding the taxation of mineral rights, specifically focusing on Entry 50 of List II of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution. This entry deals with taxes on mineral rights, subject to Parliament’s limitations on mineral development. Mines and mineral development are listed under both the Union List (Entry 54 of List I) and the State List (Entry 23 of List II). Parliament enacted the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 (MMDR Act) under its legislative powers, predominantly covering Entry 54 of List I. The MMDR Act is a comprehensive code regulating mines and mineral development, with Section 9 mandating royalty payments for minerals removed or consumed from leased areas.

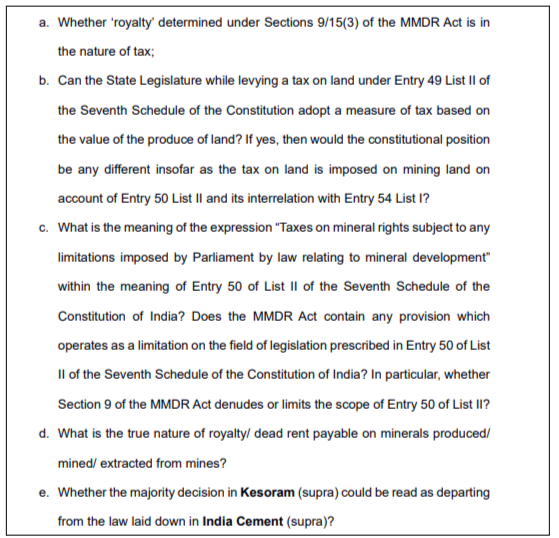

A seven-judge Bench, in India Cement Ltd. vs. State of Tamil Nadu, previously held that royalty is a tax, and State legislatures lack the competence to levy taxes on mineral rights due to the MMDR Act’s coverage. However, a Constitution Bench in State of West Bengal vs. Kesoram Industries Ltd, later clarified that royalty is not a tax. State legislatures then imposed taxes on mineral-bearing land under Entry 49 of List II, using mineral value or royalty as the tax measure. States like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh also imposed environmental and health cesses and fees for transporting coal and coaldust. The constitutional validity of these levies was challenged, leading to a three-judge Bench referring the following questions to a nine-judge Bench for a decisive ruling due to inconsistencies between earlier rulings.

Senior Advocate Rakesh Dwivedi, representing the State of Jharkhand, argued that the term “limitation” in Entry 50 of List II, which pertains to the State’s power to tax mineral rights, signifies placing a cap on the power to tax rather than transferring this power to Parliament entirely. Conversely, the Union and the Eastern Zone Mining Corporation argued that the language of Entry 50 in List II goes beyond just development or conservation, being specifically crafted for the holistic national welfare.

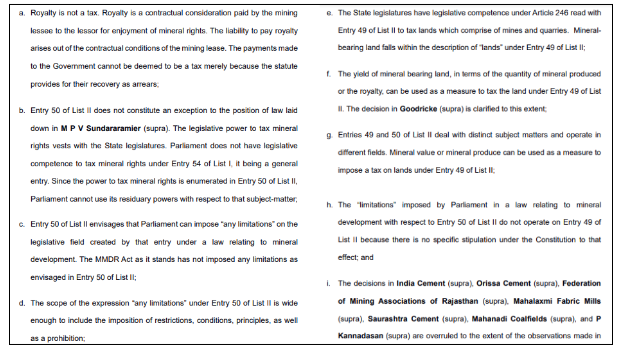

Upon hearing arguments from both ends, the Court in a majority judgement held that Royalty is not a tax, and the legislative power to tax mineral rights vests with the State legislatures. Parliament does not have legislative competence to tax mineral rights under Entry 54 of List I, it is a general entry. Further, the State legislatures have legislative competence under Article 246 read with Entry 49 of List II to tax lands which comprise of mines and quarries.

The court posted the question of whether the judgement applies prospectively to the next hearing in the next week. Accordingly, all appeals are disposed of.

Kerala HC: Sexual crimes cannot be resolved through compromise, but “peaceful family life” can be considered on humanitarian grounds if the accused and victim get married.

In XXX vs. State of Kerala, the Kerala High Court held that settlement of cases including the offence of rape and POCSO Act offences is not permissible under the law. However, the tough obstacles to settlement should be overcome with humanitarian considerations, with “Peaceful family life” being one such humanitarian grounds, to ensure the well-being of their marriage.

The single-judge bench of Justice A. Badharudeen was hearing a petition to quash the final proceedings in a sexual crime case. The brief facts of the case are as follows. On 21 February 2021, at about 10:30 am, the first accused kidnapped the 17-year-old victim from the lawful custody of her guardians/parents. He then subjected her to sexual intercourse while detaining her under his illegal custody, resulting in her pregnancy. The prosecution alleges that the second accused, the victim’s mother, failed to report the incident to the police. Consequently, the first accused faces charges under Sections 366, 342, 370, 370A, 376(2)(n) of the Indian Penal Code and Sections 5(l)(j)(ii) read with 6, 4 read with 3(a) of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO Act). The second accused is charged under Section 21(1) of the POCSO Act.

The petitioners’ counsel submitted that the matter has now been settled, as evidenced by an affidavit from the victim stating that she married the first accused on 25 August 2021, and they have been living happily as husband and wife. A copy of the marriage certificate was also produced. The prosecution and the victim’s counsel support this settlement, noting that the couple now has two children and is living happily.

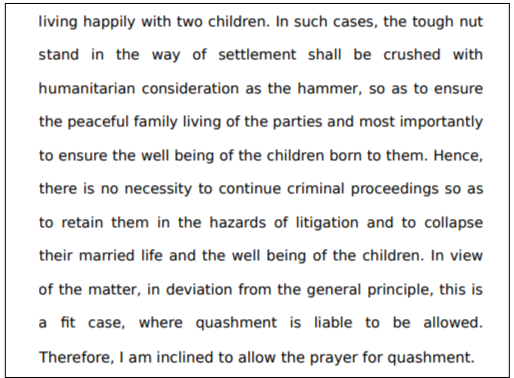

Upon hearing both sides, the court looked at the power to quash criminal proceedings under section 482 of the CrPC. The court observed that serious offences such as murder, rape, and dacoity, or offences of moral turpitude under special statutes like the Prevention of Corruption Act, cannot be settled through compromise between the offender and the victim. In cases of rape or attempted rape, compromise is unthinkable as these crimes violate a woman’s dignity and reputation, which are invaluable. Any pressure on the victim to marry the perpetrator is unacceptable, and the courts must avoid any soft approach to such cases. Grave offences involving mental depravity or serious social impact cannot be quashed even if the victim’s family has settled the dispute, as these crimes affect society at large. Quashing such offences would send a wrong signal and potentially benefit habitual offenders.

However, in this case, despite the first accused’s initial crime of molestation leading to pregnancy, the subsequent marriage and happy family life, including the birth of two children, provide grounds for considering the quashing of criminal proceedings. To ensure the peaceful family living of the parties and the well-being of the children, humanitarian consideration should prevail, allowing for the quashing of the case to avoid disrupting their married life and subjecting them to further litigation hazards. Thus, this case merits deviation from the general principle, making quashment appropriate.

Accordingly, the criminal proceedings are quashed.

Kerala HC: Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 prevails over the Muslim Personal Law.

In Moidutty Musliyar vs. Sub-Inspector Vadakkencherry Police Station, the Kerala High Court held that when the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 prohibits child marriage, it overrides Muslim personal law. Every citizen in this country, regardless of their religion, is subject to the law of the land, which is Act 2006.

The Single judge bench of Justice PV KunhiKrishnan was hearing a petition to quash the proceedings against the petitioners involving charges of child marriage under Sections 10 and 11 of the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act. The case pertains to an alleged child marriage conducted in Vadakkancherry, Palakkad district, according to Islamic rites. The first accused, the father, is charged with marrying off his minor daughter to the second accused. The third and fourth accused are the President and Secretary of the Islam Juma Masjid Mahal Committee, and the fifth accused was a witness to the marriage.

The petitioners contended that under Islamic law, a Muslim girl has the ‘Khiyar-ul-bulugh’ or ‘Option of Puberty,’ which allows her to marry upon reaching puberty, usually at 15 years old. They argued that a minor girl’s marriage is not void but voidable at her discretion once she reaches puberty. They claimed that Muslim personal law takes precedence over the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act.

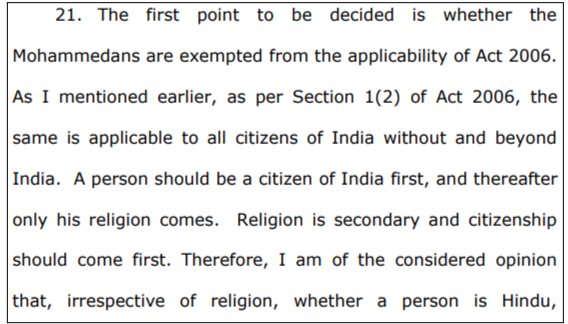

The court looked at the objectives and reasons behind the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, of 2006. It emphasized that it applies to all citizens of India, regardless of their religion, and has extra-territorial jurisdiction.

The court remarked that every Indian is a citizen of the country first and a member of their religion second. When the Act 2006 prohibits child marriage, it overrides Muslim personal law. Therefore, every citizen in this country, regardless of their religion, is subject to Act 2006 as the law of the land.

Further, relying on multiple judgements of the courts, it is held that it is a well-established principle that when the provisions of a statute are repugnant to or contrary to customary or personal law. There is no specific exclusion of the said customary or personal law from the statutory provisions, the statute will prevail. The personal or customary law shall stand abrogated to the extent of the inconsistency.

Accordingly, the case is dismissed.

Andhra Pradesh HC: “Unfounded apprehensions” cannot be relied upon to curtail right to freedom of movement.

In Venkateswara Rao Maladi vs. The State of Andhra Pradesh, the Andhra Pradesh High Court held that the Order to deposit the passport before the Court is violative of the freedom of movement of the petitioner under Article 19 of the Constitution, particularly if it is done based on the “unfounded apprehensions”.

The High Court was hearing a criminal petition for the expeditious release of the petitioner’s passport. The petitioner was working with TruJet Airlines from December 2014 to July 2020 and needed to get his passport reissued after it was allegedly stolen. To reissue his passport, he filed a petition for a No Objection Certificate. However, the petitioner is an accused along with his father in a case, initially charged under Section 326 R/w.34 IPC, later altered to Sec.506 R/w.34 IPC.

The Additional Public Prosecutor requested that the petitioner secure his presence before the Court to face trial and ensure the passport is not misused. There was apprehension that the petitioner might travel internationally, potentially hampering the trial. Therefore, a direction was given to the Regional Passport Officer, Vijayawada, to issue the passport per the law and produce it directly before the Court. The passport was re-issued and submitted to the Court. The petitioner then filed a petition under Section 451 Cr.P.C. for the return of the passport, which was returned.

The counsel for the petitioner argued that the direction to deposit the passport violates the petitioner’s freedom of movement under Article 19 and the right to life and liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

Hearing both sides, the High Court relied on the apex court’s judgement in Suresh Nanda vs. C.B.I, where it was held that even the Court cannot impound a passport. Although Section 104 Cr.P.C. states that the Court may, if it deems fit, impound any document or thing produced before it, this provision is interpreted to apply only to documents or things other than passports. Further, to curtail any such fundamental right to freedom of movement under Article 19, there must be due procedure established by law.

Accordingly, the order withholding the passport is set aside and the trial Court is directed to return the passport of the petitioner.

Calcutta HC: A female cannot be an accused under Section 354A of the IPC, as it is gender specific.

In Susmita Pandit vs. State of West Bengal & Another, the Calcutta High Court held that as a result of the specific words “a man” used in the Section 354A sub-sections (1), (2) and (3) of the IPC, a female cannot be an accused under Section 354A of the IPC. It is very gender specific.

The single-judge bench of Justice Ajay Kumar Gupta was hearing a criminal revision petition to quash the proceedings initiated against them. The brief facts of the case are as follows. On 15 September 2018, Opposite Party No. 2 lodged a complaint with the Officer-in-Charge of Netaji Nagar Police Station against four individuals, including the petitioner. The complaint alleged that Samir Pandit and the petitioner attempted to torture the complainant’s mother. It was claimed that Samir Pandit had entered the complainant’s room while she was changing clothes and attempted to molest her, though she managed to escape. Consequently, Netaji Nagar Police Station Case No. 312 of 2018 was registered under Sections 354A/506/34 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Samir Pandit is the petitioner’s biological father. The FIR also accused the petitioner of instigating and torturing the complainant’s mother along with others, though no specific details were provided regarding the petitioner’s role in the alleged offences.

The counsel for the petitioner highlighted that the elements of Section 354A and Section 354 are distinct, and Section 354A cannot be applied to female accused. The State’s counsel argued that the FIR named all accused, including the petitioner, who was alleged to have threatened the complainant and her mother. The investigation, including witness and victim statements under Sections 161 and 164 of the CrPC, purportedly established a prima facie case against the petitioner under Sections 354A/506/34 of the IPC.

Upon hearing both sides and relying on the apex court’s judgement in Tolaram Relumal and Anr. vs. The State of Bombay, whereby it was held that in the interpretation of penal statutes when a provision can reasonably be understood in more than one way, the Court should adopt the interpretation that is less likely to impose a penalty.

Accordingly, it is clear that a female cannot be an accused under Section 354A of the IPC, given the language of the statute. The term “a man” in Section 354A (1), (2), and (3) of the IPC explicitly limits the applicability of this provision to male individuals. Consequently, a female accused does not fall within the scope of this section’s provisions. The allegation of an offence punishable under Section 354A of IPC is not applicable against the present petitioner.