In this hundredth edition of court judgements review, we look at the judgements of the Supreme Court in matters of fee regulation in private medical colleges, appointment of vice-chancellors in universities, repudiation of contract based on IRDA Regulations, Delhi High Court’s decision on bail in POCSO case, and Kerala High Court’s decision on termination of pregnancy.

Supreme Court: Education is not a business to earn profit. The tuition fee shall always be affordable.

In Narayana Medical College vs. The State of Andhra Pradesh & Ors., the Supreme Court quashed a Government Order (G.O.) issued by the State of Andhra Pradesh, that sought to increase the tuition fee of private medical colleges by seven times. The apex court remarked that the tuition fee shall always be affordable, and education is not a business for earning profit.

The two-judge bench comprising of Justices MR Shah and Sudhanshu Dhulia was hearing an appeal filed by the medical college against the judgement of the High Court of Andhra Pradesh that had earlier quashed the G.O. In an early judgement in P.A. Inamdar and Ors. vs. State of Maharashtra and Ors, the apex court authorized the states to fix the maximum amount that can be charged as fees to prevent the commercialisation of the education system. Accordingly, the Andhra Pradesh Government has passed the Andhra Pradesh Admission and Fee Regulatory Committee (for Professional courses offered in private unaided professional institutions) Rules, 2006.

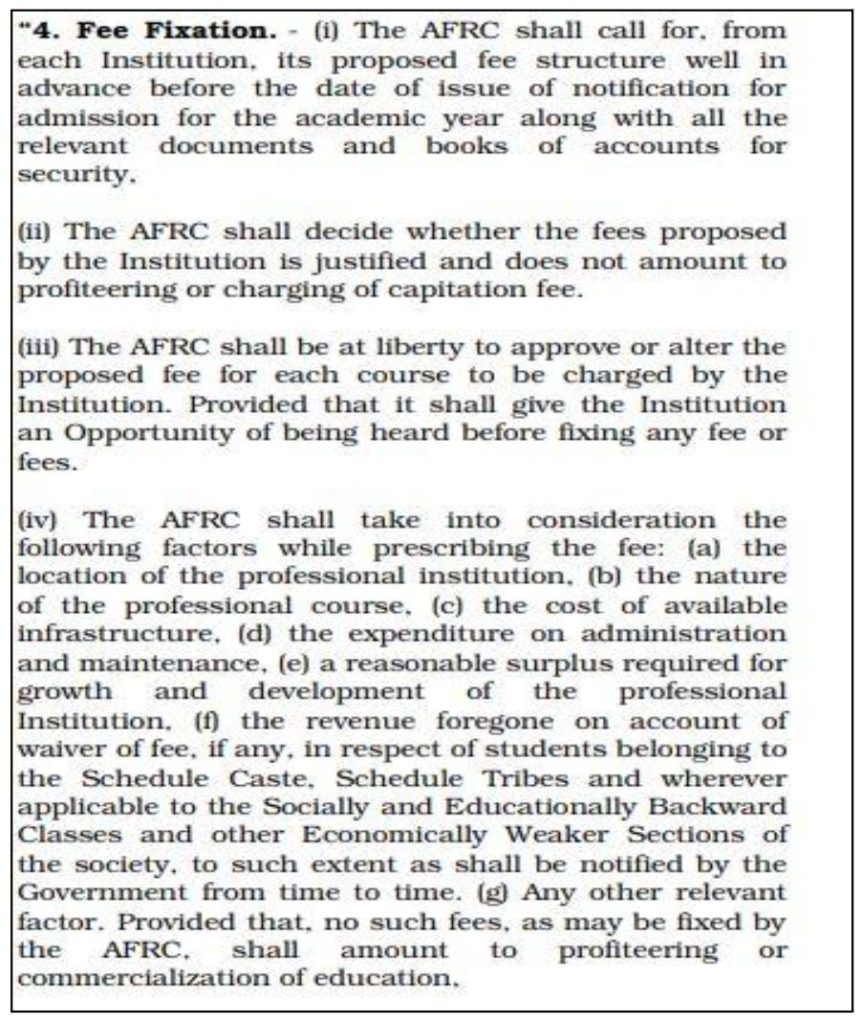

Rule 4 of the above rules provides for the fee fixation by the Admissions and Fees Regulatory Committee (AFRC).

For the academic years 2017 to 2020, the State Government, without waiting for the report of AFRC, and following representations from Private medical colleges, enhanced the tuition fee by seven times to twenty-four lakh per annum. The apex court agreed with the judgement of the High Court and held that decision of this Court in the instance of P.A. Inamdar as well as the pertinent sections of the Rules, 2006, both forbid raising the tuition fee without the AFRC’s recommendations.

On the question of the High Court’s decision to refund the fee that is already being collected, the apex court held that if the AFRC’s proposal is higher than the earlier fee, the colleges are open to recovering the same. However, till such time, retaining the funds collected pursuant to an illegal G.O is prohibited and the High Court’s judgement in this regard is error-free. Accordingly, the petition is dismissed, and a cost of 5 Lakhs is imposed which is to be paid by the appellant and the State Government, equally.

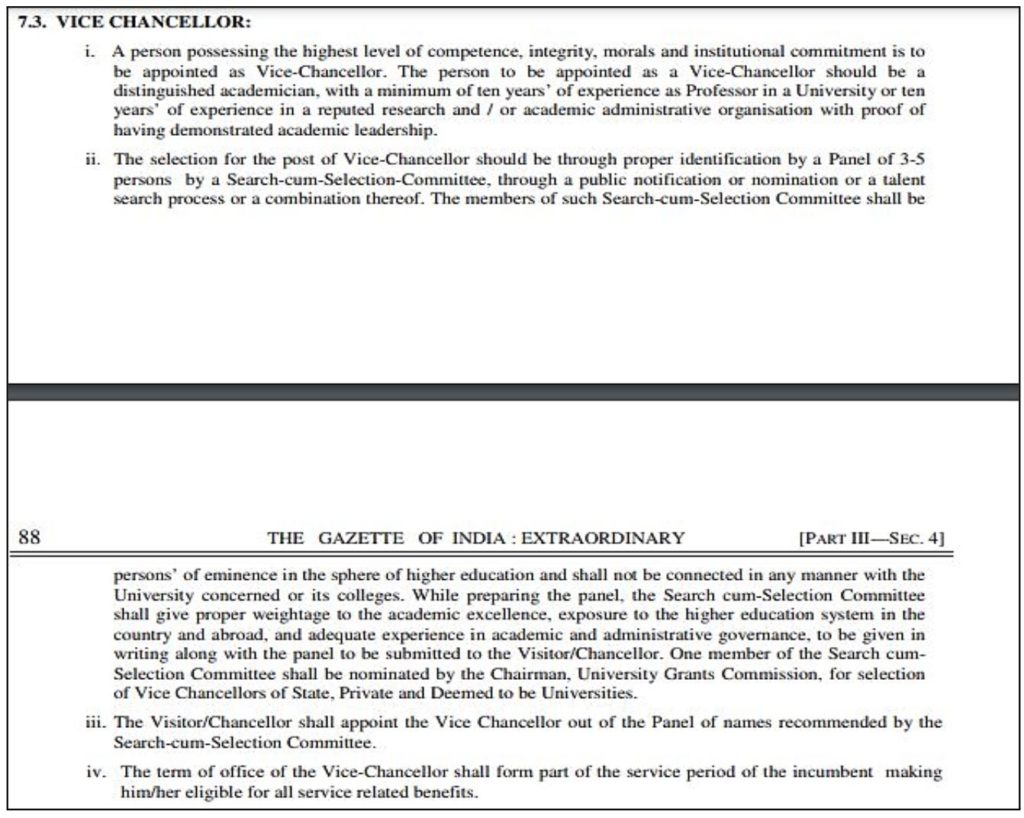

Supreme Court: As per UGC Regulations, 2018, the selection for the post of Vice-Chancellor should be through proper identification from a ‘panel of names’ recommended by a Search-cum-Selection Committee.

A two-judged bench of the Supreme Court, in Prof. Narendra Singh Bhandari vs. Ravindra Jugran and Others, set aside the appeal against the decision of the Uttarakhand High Court which quashed the appointment of the appellant as the Vice-Chancellor of Soban Singh Jeena University.

Aggrieved by the decision of Uttarakhand High Court, the appellant approached the apex court regarding the appointment to the post of vice-chancellor to the Soban Singh Jeena University. The original petitioner claimed that selection as Vice-Chancellor was unlawful because just one name was presented to the Chief Minister by the Search Committee, and he was chosen and appointed as Vice-Chancellor without any further notice.

In defence, the original appellant contended that as per the Soban Singh Jeena University Act, 2019, there was no such requirement of having a minimum of 10 years experience as a Professor, and the appellant claimed that he had enough expertise and merit was not compromised in any way. However, the High Court set aside the appointment by holding that such an appointment is contrary to section 7.3 of the UGC Regulations, 2018.

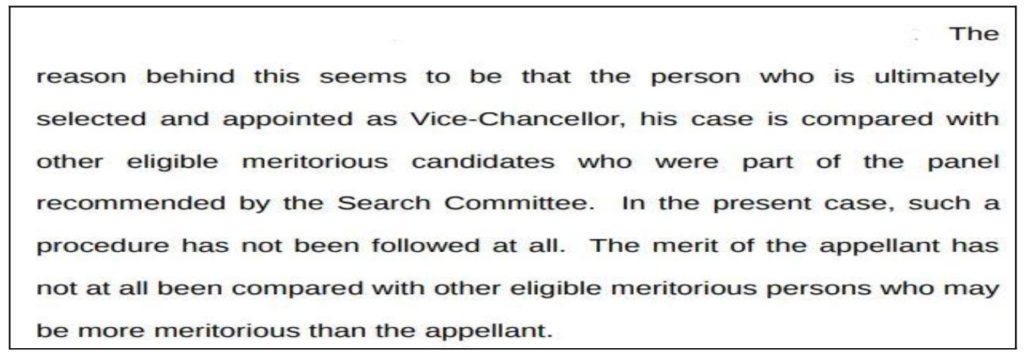

Upon hearing the arguments from both sides, the apex court held that in this instance, it is not fair to say that the appellant’s appointment as vice chancellor complies with the requirements of Section 10 of the University Act, 2019, in accordance with Regulation 7.3 of the UGC Regulations, 2018. And regarding the argument of the appellant that he was meritorious, and merit was not compromised during the appointment, the court held that

Accordingly, the appeal is dismissed, and the High Court judgement is upheld.

Supreme Court: Any non-compliance of Clause (3) and (4) of the IRDA Regulation, 2002 on the part of the insurance companies would take away their right to plead repudiation of the contract.

In M/s Texco Marketing Pvt. Ltd. vs. TATA AIG General Insurance Company Ltd. & Ors., the Supreme Court cautioned the insurance companies that any non-compliance of Clause (3) and (4) of the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (Protection of Policyholders’ Interests) Regulations, 2002 on the part of the insurance companies would take away their right to plead repudiation of the contract by placing reliance upon any of the terms and conditions included thereunder.

A two-judge bench comprising of Justice Surya Kant, and Justice M.M. Sundresh, was hearing a challenge against the decision of the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission, which overturned the decision of the State Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission that held that the insurance company indulged in unfair trade practice by not adequately disclosing the Exclusion Clauses.

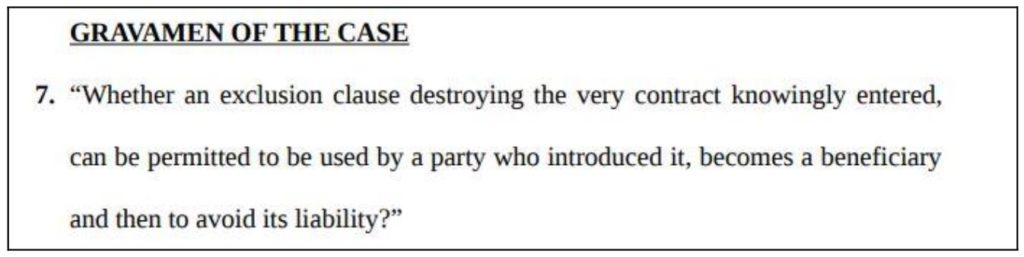

The apex court has identified the core legal issue as below.

Insurance contracts are one form of an Adhesion contract. These agreements are created by the insurer using a standard format, and the customer is required to sign them. He/she has very few options or choices, other than to sign on the dotted line, regarding the contract’s stipulations. A consumer may choose to enter into an insurance contract, but the clear intent is to cover any eventuality that may arise in the future. Because of this, is required of an insurer to cover the risk as opposed to a reasonable repudiation, and to do so from the perspective of the consumer.

It is necessary to interpret an exclusion clause in an insurance contract differently. When reliance is placed on such a clause, the insurer bears both the responsibility and the burden. This is due to the unique nature of insurance contracts, which are founded on the idea of good faith. Being a contract of speculation, it is not intended to be used as leverage or a safety net for the insurer but rather to be called upon in the event of an emergency. Due to the nature of insurance contracts, all parties are required to provide all relevant information.

An exclusion provision can never be interpreted to suggest that the primary goal for which the contract was made is at odds with it. Further,

The three things mentioned above are linked together and overlap. The insurer’s primary responsibility is to carry out a proper disclosure and notification in both text and spirit. Non-disclosure and a failure to provide a copy of the said contract by following the procedure required by statute would render the said clause redundant and non-existent when an exclusion clause is introduced making the contract unenforceable on the date it is executed, much to the knowledge of the insurer.

In this case, such disclosure was not made to the insured as against clauses 3 and 4 of the IRDA Regulations 2002, which provide for mandatory disclosure of all material information of the policy, and any non-compliance obviously would lead to the irresistible conclusion that the offending clause, be it an exclusion clause, cannot be pressed into service by the insurer against the insured as he may not be in the knowhow of the same. Further,

Accordingly, the apex court held that Non-compliance of Clauses (3) and (4) of the IRDA Regulation, 2002 preceded by unilateral inclusion, and thereafter followed by the execution of the contract, receiving benefits, and repudiation after knowing that it was entered into for a basement, would certainly be an act of unfair trade practice. Therefore, it set aside the order passed by the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission.

Kerala HC: Economic backwardness or the possibility of social stigma cannot compel this Court to transgress the statutory prohibition and grant permission for medical termination of pregnancy

In Ramsiyamol R S vs. State of Kerala & Ors., the single judge bench of the Kerala High Court held that in the absence of any medical reasons referable to the petitioner or the foetus, economic backwardness or possibility of social stigma cannot compel the Court to transgress the statutory prohibition and grant permission for medical termination of pregnancy.

The High Court was hearing a writ petition seeking the termination of pregnancy with a gestational age of 28 weeks. When the petition came up for admission, the court directed the Superintendent of the SAT Hospital to constitute a medical board for examining the plea of the petitioner. The medical board, upon examining the petitioner, held that the petitioner was taking good care of her pregnancy with routine ANC, and a mental health evaluation of the woman shows that she is a cognizant woman with clinically normal intellectual function and a sound mind.

The results of the ultrasound reveal a straightforward singleton live pregnancy lasting 28 weeks with no foetal or maternal problems. The Medical Board has also expressed its opposition to medically ending a pregnancy due to the risk to the unborn child.

The High Court reaffirmed the decision of the apex court in Suchita Srivastava and another vs. Chandigarh Administration, that a woman’s right to make a reproductive choice, is to be a dimension of her personal liberty.

However, the High Court held that the issue at hand is whether such freedom can violate the limitations or prohibitions imposed by the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act in situations where neither the expectant mother nor the foetus has any medical issues, and the pregnancy was being well-cared for by the prospective mother before she came to this Court.

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 prohibits the termination of pregnancy after the period of 24 weeks, which in this case is exceeded. As per the latest amendment, the length of pregnancy is irrelevant if the diagnosis of any of the substantial foetal abnormalities by a Medical Board makes a case for termination. This case does not have any such shortcomings. Accordingly, the High Court held that

The writ petition stands dismissed for the above-stated reasons.

Delhi HC: The intention of POCSO was to protect children below the age of 18 years from sexual exploitation. It was never meant to criminalize consensual romantic relationships between young adults.

In X vs. State Government of NCT of Delhi and Anr, the single judge bench comprising of Justice Jasmeet Singh granted bail to the accused arrested in the POSCO case and held that the primary intention of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 act (POCSO Act) was not to criminalize consensual relationships between young adults but to protect children below 18 years of age from sexual abuses.

The High Court was hearing a bail application against an FIR registered by the parents of the young female girl, accusing the applicant of taking the victim and marrying her, despite her being already married off by her parents when she was 17 years of age. The High Court relied on the judgement in Vijayalakshmi vs. State , where the boundary between consensual relationships and sexual exploitation was considered, as below.

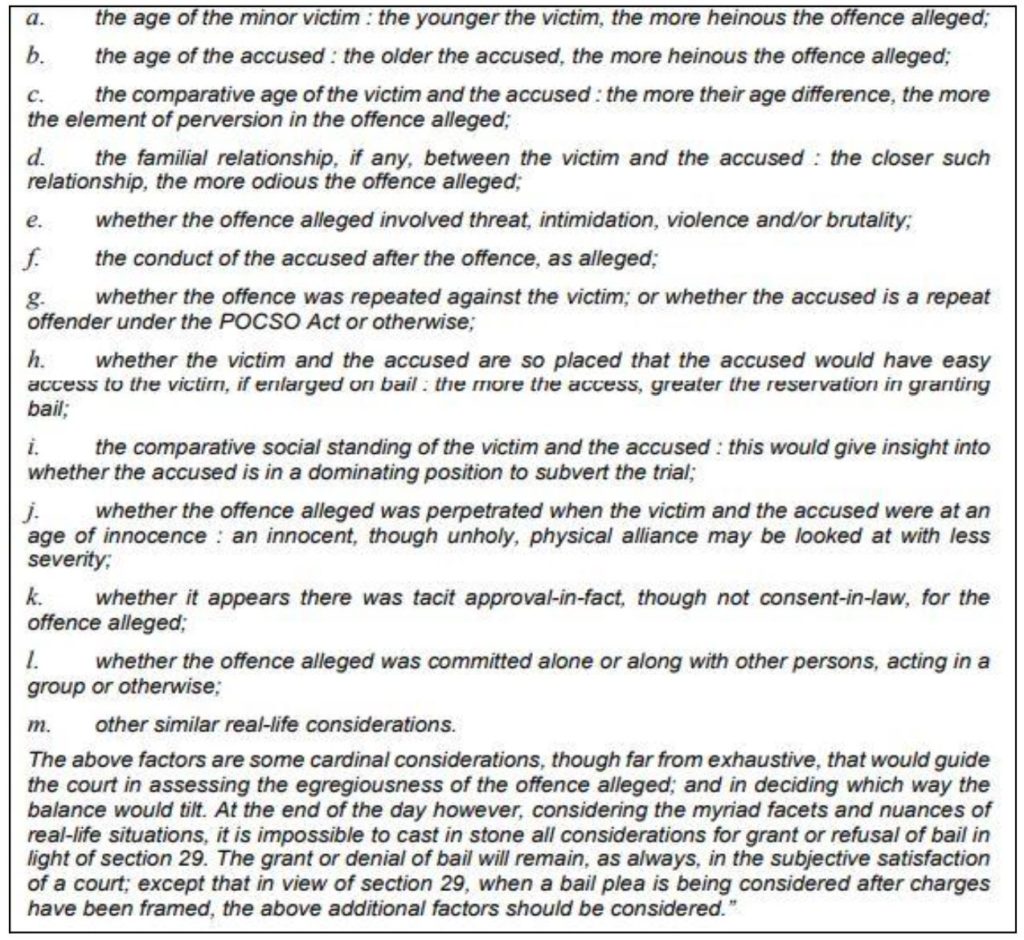

The Delhi High Court, in Dharmender Singh vs. State granted bail to a person accused in the POCSO case while taking into consideration the possibility of a reciprocal physical relationship between the accused and the minor victim. It additionally laid down a few guidelines that are to be followed while deciding on bail applications in POCSO cases.

After the interaction with the victim in the present case, the judge concluded that the victim was never coerced into a relationship, and it was a case of a consensual relationship. Though the consent of the minor doesn’t have any legal standing, the fact that there was a consensual relationship should be of consideration while deciding on the cases of bail. Accordingly, the bail is approved with certain terms and conditions. The application stands disposed of.

Featured Image: Review of Court Judgements